Tang Kwong San’s “Rootstock”

By Antonia Ebner

Installation view of TANG KWONG SAN’s "Rootstock" at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong, 2024. Courtesy GDM.

Tang Kwong San:

Rootstock

GDM

Hong Kong

Sep 12–Nov 9

“One day, fables will overlap with your personal experiences.” This quote from the artist Tang Kwong San embodies the spirit of his oil paintings, graphite drawings, and installations that were showcased in “Rootstock,” his first solo exhibition at Hong Kong’s GDM (formerly Galerie du Monde). Having grown up between Dongguan and Hong Kong, Tang creates paintings and drawings of interstitial urban locales and the objects and plants that are found there. Among the scenes he captured on his nocturnal forays were of the bauhinia flower, Hong Kong’s official emblem, which he then rendered in oil on canvas. As a species, the bauhinia is reliant on grafting for its survival—an apt analogy for Tang’s exploration of his personal and geographic roots.

TANG KWONG SAN, Bauhinia Variegata I, 2024, oil on canvas, 150 × 120 cm. Courtesy the artist and GDM, Hong Kong.

Beyond the botanical paintings in “Rootstock,” Tang depicted other curious discarded objects discovered on the street. Hanging on the wall by the entrance was a graphite drawing entitled Regurgitated Body I (2024), which depicts the sculptural mold used to create a plaster cast of a cow’s head. One’s instinct was to turn away to escape the direct gaze of the decapitated cow, only to notice Regurgitated Body II (2024) hanging separately, inviting viewers to mentally join the two components together into one body. The spatial division alluded to the fracturing of the artist’s own historical and cultural identity, with the cow’s dismemberment a representation of his struggle to define his place in Hong Kong’s sociopolitical landscape.

TANG KWONG SAN, The Woodcutter of Memories, 2024, graphite on paper, brass, in artist’s frame, 54 × 44 × 10.5 cm. Courtesy the artist and GDM, Hong Kong.

Another symbolic use of a found object could be seen in The Woodcutter of Memories (2024), which featured a graphite-drawn axe, modeled after those awarded to Hong Kong firefighters for their courage and dedication. The drawing is encased in bauhinia wood, with a brass door hinged at 45 degrees, initially obstructing a view of the interior. This work evoked Aesop’s fable The Honest Woodcutter, in which a worker is tested when God offers him gold and silver axes instead of his own—which he refuses, thereby passing a test of integrity. Tang links this fable with the symbolic meaning of the Hong Kong fireman’s axe, emphasizing the importance of hard work and dedication to the city’s identity. The motif continued with the sound of chopping wood from the video The Brass Axe & Blakeana (2024). Tang shows himself on his studio rooftop at night chipping away at a bauhinia tree with an axe. With this action, Tang visualizes his frustrations with reality, in which honesty does not always bring success as the fable promises. The persistent sound of chopping was also symbolic of a splintered identity and self-destruction.

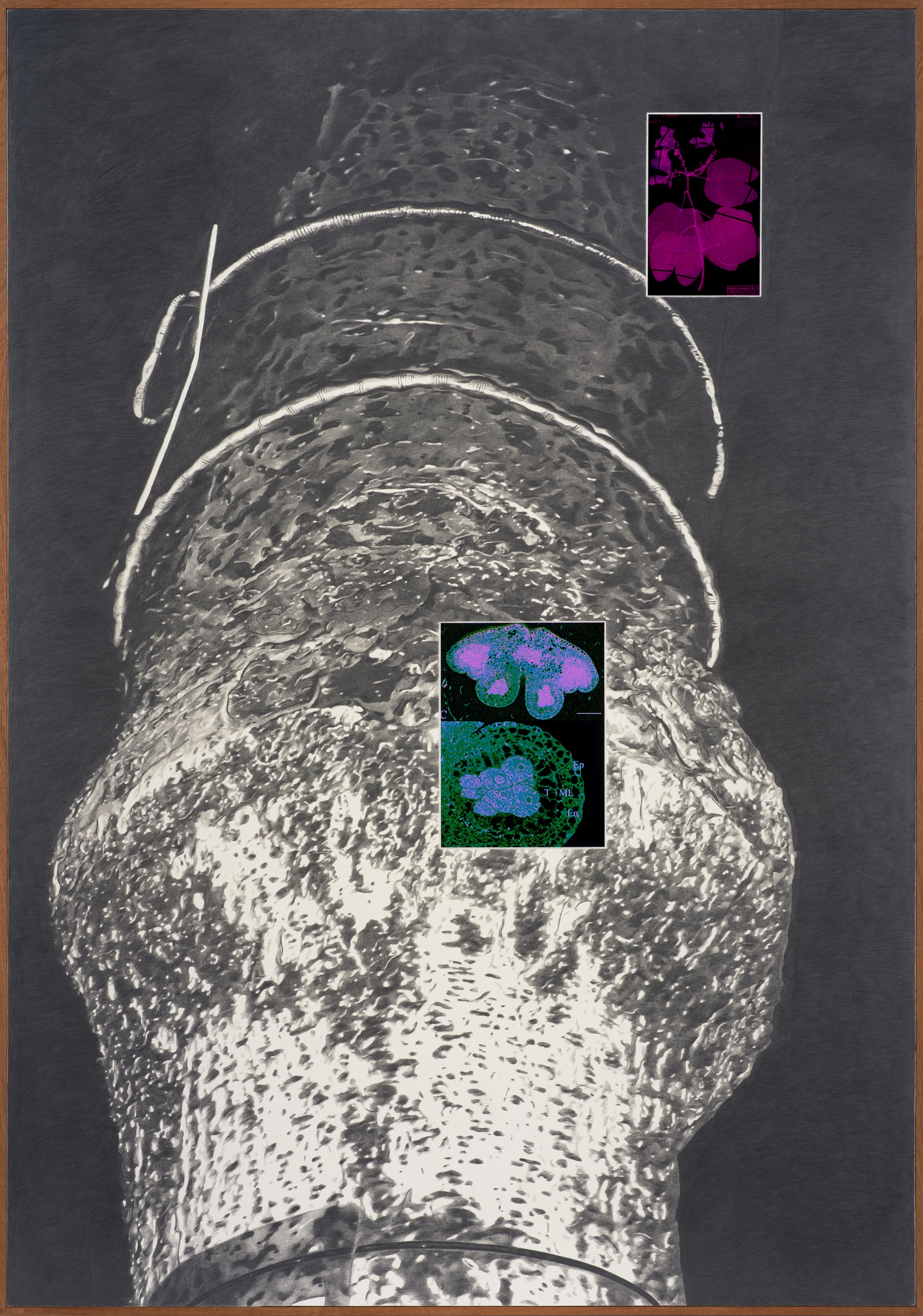

TANG KWONG SAN, Rootstock II, 2024, graphite on paper, photograph, 150 × 105 cm. Courtesy the artist and GDM, Hong Kong.

In contrast to the scenes, Tang also presented neatly cut, polished bauhinia tree trunks placed on a glass shelf: sterile and clean, devoid of roots and origin, a symbol of dislocation. He carefully slotted coins into the cracks of the wood, as if the plant was split, or perhaps held together, by the currency symbolic of Hong Kong’s colonial past. In the gallery’s center was Wishing Pond (2024), made from 24 reddish resin bricks that encased moth specimens. The moths, pronounced homophonically with “I” (ngo) in Cantonese, also relate to the name of his late mother, and evoke the spirits of lost family members in Chinese folklore.

With a thoughtful curatorial presentation, “Rootstock” reflected Tang’s ongoing ambition to understand diasporic identities—in his case, one deeply rooted in, but also subtly divergent from, a shared history of Hong Kong. “Rootstock continues a section of grafted history,” he wrote of the exhibition, suggesting that individual identities can be both splintered and joined.

Antonia Ebner was an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.