Acts of Nullification in Park Seo-Bo and Ha Chong-Hyun

By SOPHIA POWERS

.jpg)

Installation view of PARK SEO-BO’s "The Newspaper Ecritures, 2022-23" at White Cube, New York, 2025. Photo by Frankie Tyska. Courtesy the Park Seo-Bo Foundation and White Cube.

Park Seo-Bo

The Newspaper Ecritures, 2022–23

White Cube, New York

Nov 8, 2024–Jan 11, 2025

Ha Chong-Hyun

50 Years of Conjunction

Tina Kim Gallery, New York

Nov 7, 2024–Dec 21, 2024

If the Korean monochrome

movement known as Dansaekhwa has been typically understood as exemplifying notions

of emptiness and non-action, then one has to marvel at just how many of its central works have resonated with viewers. This tension between cause and effect was

explored in two recent exhibitions in New York—Tina Kim Gallery presenting Ha

Chong-Hyun’s Conjunction series (1974– ) and White Cube showcasing Park

Seo-Bo’s The Newspaper Ecritures series (2022–23), completed in the

final years of the artist’s life. Park’s and Ha’s works have often been

understood through the influence of Asian spiritual traditions that emphasize

emptiness and the obfuscation of ego, yet the paintings here surged with a

vitality unmistakably unique to their makers’ personal vision.

The concept of “conjunction,” from which Ha Chong-Hyun’s series takes its name, refers to the unification of paint and canvas—a seemingly banal, if accurate, way of describing conventional painting. But Ha adroitly complicates this relationship by pushing paint through the back of the burlap canvas so that it protrudes onto the front of the picture plane through the small gaps between the fiber’s weave, like beads of perspiration. Without applying additional paint, Ha then brushes and scrapes the exuded pigment to form abstract minimalist motifs on the canvas’ front. For example, Conjunction 24-20 (2024) evokes various elements found in nature—mist and rain—while the most dramatic of his paintings bring to mind the urban cityscape, like in Conjunction 24-17 (2024). Another, Conjunction 14-694 (2014), which was displayed prominently in the first gallery, features four concrete gray columns rising from the bottom of the burlap. These were made by scraping the surface paint up from the canvas’s base, with the artist’s tool accumulating paint as the gesture extends so that the top of the line concludes in an overhang of excess paint so thick and sculptural that it casts shadows like the eaves of a building.

HA CHONG-HYUN, Conjunction 24-17, 2024, oil on hemp cloth, 182 × 227 cm. Photo by Ahn Cheonho. Courtesy the artist and Tina Kim Gallery, New York.

Installation view of HA CHONG-HYUN’s Conjunction 14-694, 2014, oil on hemp cloth, 182 × 227 cm, at "50 Years of Conjunction," Tina Kim Gallery, New York, 2024. Photo by Hyunjung Rhee. Courtesy the artist and Tina Kim Gallery.

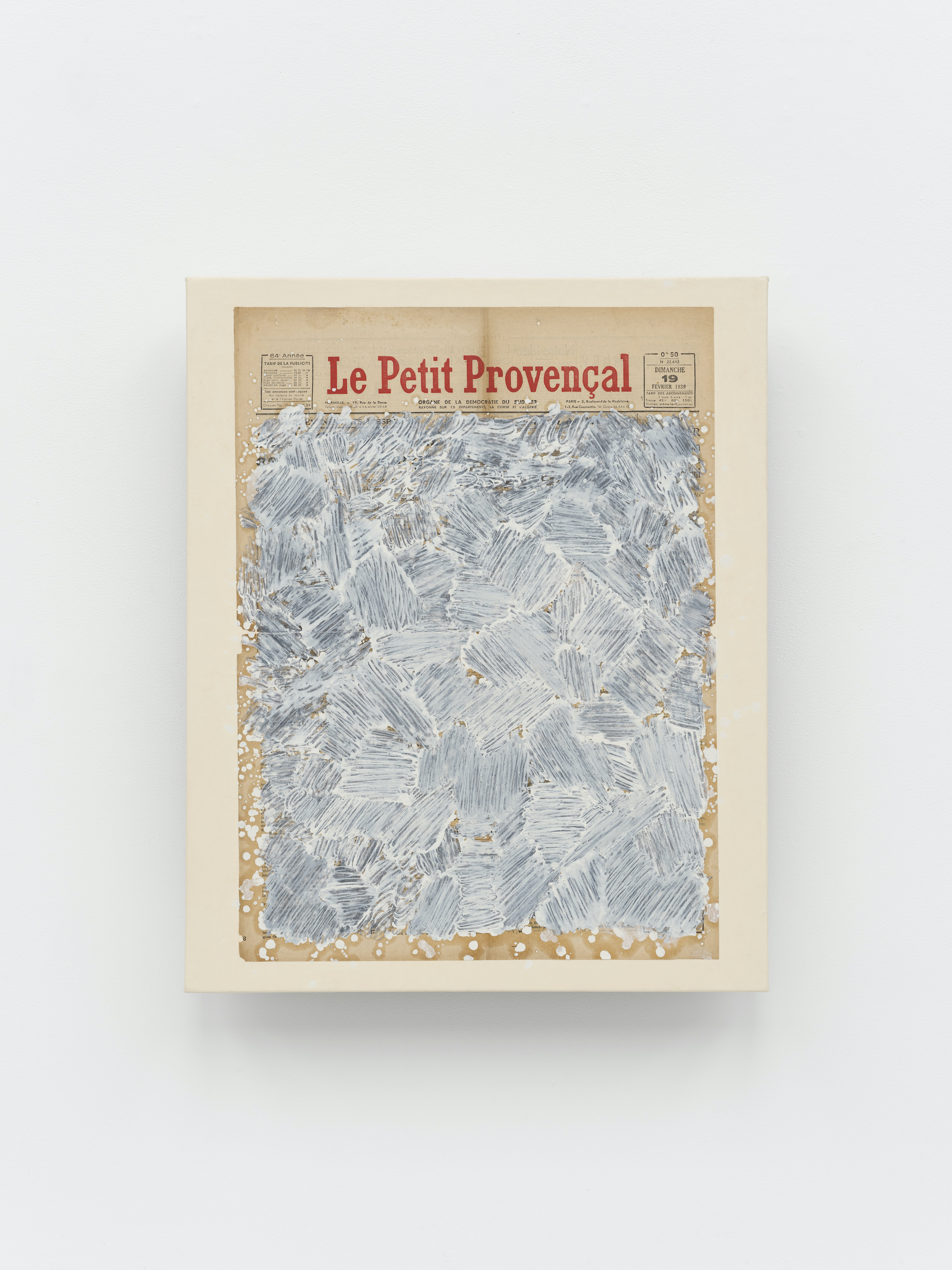

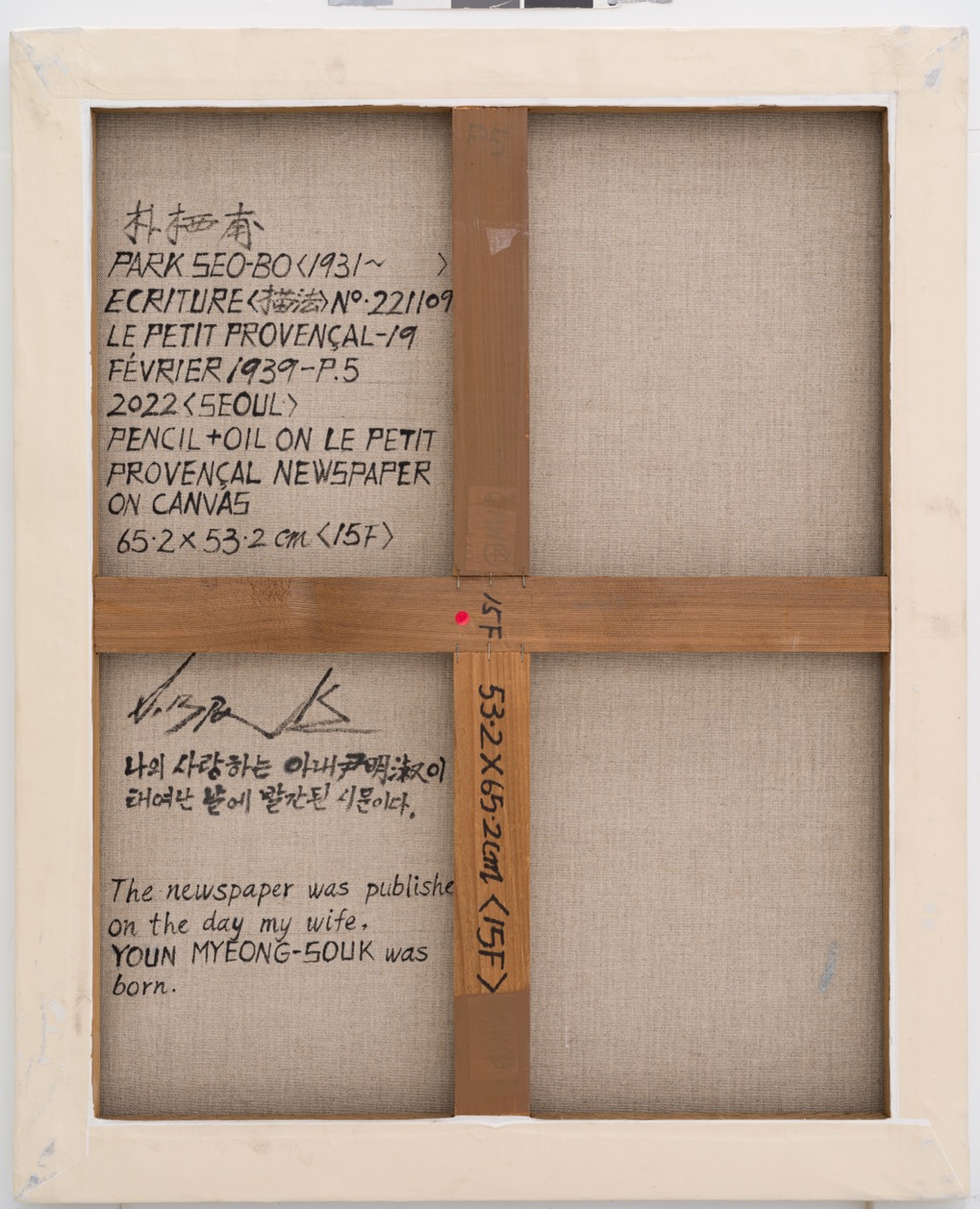

Park Seo-Bo similarly experimented with this relationship between surface and ground in his Ecriture series, albeit with less sculptural bravado. Each work consists of repetitive mark-making on old newspapers; in some cases the text is almost completely obscured as if obliterated by a blizzard. More often, Park selectively painted around sections of text so that the viewer is able to make out various bits of information—such as his wife’s birthday in Ecriture No. 221109 (2022) or the title of the French newspaper Le Petit Provençal in Ecriture No. 221115 (2022). This tethering of meditative abstraction to the concrete particulars of time and place in the broader world was what most interested Park in the final series of a distinguished career.

.jpg)

PARK SEO-BO, Ecriture No. 221109, 2022, pencil and oil on newspaper on canvas, 65.2 × 53.2 cm. Photo by Frankie Tyska. Courtesy the Park Seo-Bo Foundation and White Cube, New York.

The reverse of PARK SEO-BO’s Ecriture No. 221109, 2022, 65.2 × 53.2 cm. Photo by Frankie Tyska. Courtesy the Park Seo-Bo Foundation and White Cube, New York.

Park Seo-Bo and Ha Chong-Hyun, along with other leading members of the Dansaekhwa movement—Lee Ufan, Hur Hwang, Lee Dong-Youb, and Yun Hyong-Keun—have been credited with forging a mode of abstract painting distinct from their Western counterparts. Typically, the specificity of local materials, as opposed to the conventional stretched canvas, is foregrounded in discussions concerning what set Dansaekhwa apart. Park’s practice of painting on newspaper was initially born out of his relative poverty as an art student in Paris, while the burlap foundation so instrumental to Ha’s practice of extruding paint from the back of the surface has been attributed to material scarcity in Korea following the war. But the dominant refrain in critical discourse surrounding this movement tends to be focused on the connection between the cohort’s artistic practice and Asian spiritual traditions, in particular Buddhism and Taoism. In the case of Park and Ha, the pursuit of “emptiness” has been highlighted by both artists, as well as their critics. Park even once remarked: “In Western art, displaying something assiduously means expressing one’s thoughts, but my art is a place that takes me out, turns me into nothing, eliminates me, and nullifies me.”

While a sentiment of non-attachment and the drive to nullify the ego provides a concise framework for viewers to ascribe meaning and originality to the paintings of Park and Ha, it also expresses a profound contradiction rarely, if ever, addressed in the critical reception of their work. If the artist seeks to eliminate the self, then why make marks at all? Why create physical objects meticulously displayed in blue-chip galleries clamoring for attention from wealthy collectors? Park contrasts his work with Western art, which he characterizes as “expressing one’s thoughts,” yet how can this statement be interpreted as anything other than a clear proclamation of the artist’s own unique perspective? Details of his work accentuate the very personal particularities of his practice, such as the selection of a newspaper printed on his wife’s birthday. While Ha’s and Park’s works exude a formal elegance that justifies their place in the canon, striving for emptiness too feels like an empty claim.

Sophia Powers is a writer based in New York.