Missing the Mark at “S.H. Raza (1922–2016)”

By Misty-Dawn MacMillan

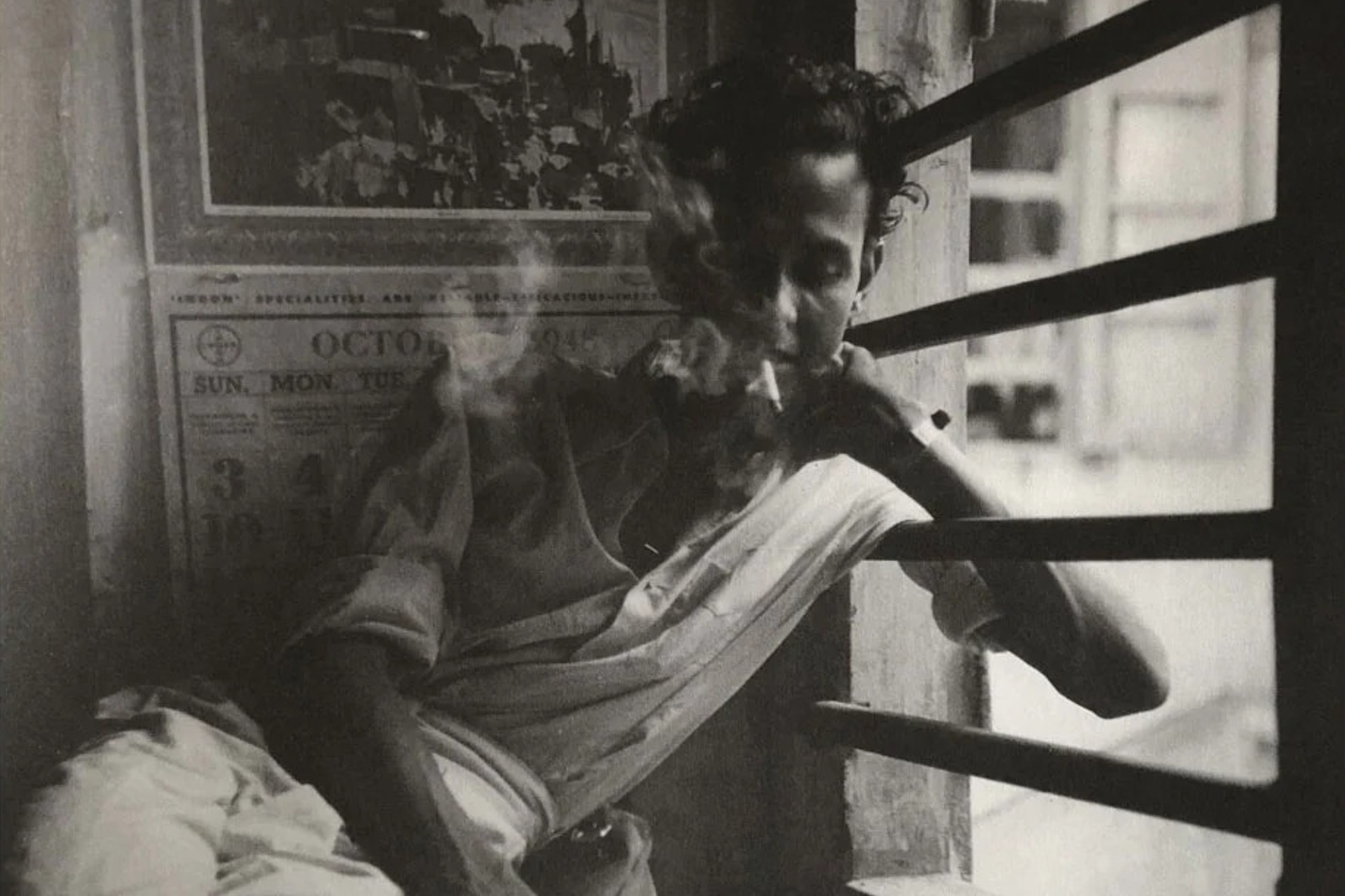

Portrait of SH RAZA. Courtesy The Raza Archives and Centre Pompidou, Paris.

“S.H. Raza (1922–2016)”

Centre Pompidou, Paris

Feb 15–May 15, 2023

“S.H. Raza (1922–2016),” the titular exhibition curated by Catherine David and Diane Toubert at the Centre Pompidou, was a chronological survey of the artist’s formal and conceptual development that hit and missed.

The exhibition opened with a spotlight photograph of Raza as a young man in his Bombay studio in 1948 and captures the artist in the wake of personal and political upheaval. While India gained its independence from the United Kingdom on August 15, 1947, Raza was grieving the passing of his mother in July. The same year, he graduated from the Sir J.J. School of Art and founded the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG) with classmates to establish an Indian vocabulary of modernism and protest the academic realism of the Bombay School and the revivalism of the Bengal school. An Indian artist at heart, with one arm firmly resting out the window to a changing landscape, the cool breeze of a foreign influence blows over him. The portrait felt emblematic of his subsequent transcultural development.

It should be noted though that while the city now goes by Mumbai, the portrait and opening exhibition panel used the name “Bombay” to historically situate Raza in the colonial context he was raised and educated. The online documentation for this very same portrait however reads, “S.H. Raza dans son atelier, Mumbai.” Bombay didn’t become Mumbai until 1995. Changing its name in the online documentation was confusing, historically inaccurate, and erased its colonial context.

Among the following vibrant Impressionist watercolors, I struggled to see the “photographic vision” we were told in the section text for “Benares, 1944” that Raza developed. True, his townscapes may have emulated the framing of landscape tourist postcards, yet early landscape photographers borrowed their framing techniques from landscape painters, and the term “photographic” inevitably elicits a technique more reminiscent of the academic realism that Raza intentionally evaded.

We were simultaneously told of Raza’s exposure to the works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque at an exhibition of reproductions of Modern French paintings on loan from the MoMA at the Bombay Art Society in 1947, yet we’re scolded against seeing Cubism in the text accompanying the painting Still Life (1949). When we’re told of the formal simplification found in traditional Indian miniature but not told about Cubism’s heavy-handed borrowing from African art, it felt more like gaslighting than cultural sensitivity. Apparently geometrization is more “inclusive” vocabulary when it’s too much work to acknowledge cultural appropriation.

The text that accompanied the collection of nudes missed the opportunity to consider the conflicting narratives surrounding the nude in India’s history. Amorous depictions are readily seen on the temple of Khajuraho and in Kangra miniature paintings. Since the establishment of the Sir J.J. School of Art in 1857, nude life drawings have been part of the curriculum, but public exhibitions of these works are considered obscene. The text discussed the censorship of Raza’s peers, yet failed to acknowledge how British dismissiveness of the Indian nude as primitive rooted for a continual puritanical gaze that affects public exhibitions of art to this day.

The exhibition section “Les feux de Paris” (“The Fires of Paris”) was named after a 1960 poem by Louis Aragon. The passage “It’s here that your fate lights up / One does not choose his bonfire” seemed to illustrate a turning point in Raza’s career rather than the Abstract Expressionist cityscapes that lined the walls. The accompanying text explained, in less passionate terms, the meeting of his wife, important collectors, contemporary artists, and the gallerist who supported his career before it was catapulted into the international market after he won the prestigious Prix de la Critique in 1956. The display tables that framed this section were filled with photographs and ephemera documenting his accomplishments and relationships.

SH RAZA, La Terre, 1977, acrylic on canvas, 174 × 260 cm. Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Dehli. Courtesy The Raza Foundation and Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Rounding the corner to the “Sacred Geographies” section, the color field paintings visually popped off the black inner wall. The impact was so appealing, it took effort to recall the infamous La Terre (1977) on the white walls opposite. It was unfortunate that the Sanskrit texts written on several of the paintings would be easy for a Western eye to dismiss as their only acknowledgement was in their partial inclusion in the painting’s titles and in an online tour given by Toubert where English captions weren’t available as advertised.

The significance of the color black was described in the final section’s exhibition text as “the mother color in Indian thought.” This is incorrect. Black in Indian culture is associated with negative energy. Black as the “mother color” in Indian thought, belonged to the thought of one Indian in particular—SH Raza. Even that simplification is reductive. Basic color theory tells us that black contains all colors at once. This, for Raza, indicated that black was imbued with limitless potential. He manifested this concept in the mature Bindu works that close the show in a section named after British critic Clive Bell’s notion of the “significant form.” It was ironic that a survey of Raza’s monumental contribution to Indian modernism began and ended with British colonialism—whether that was the intention or just an uncanny coincidence of the curatorial team—but somehow, I believe he deserved better.