“Melancholia”

By Rathsaran Sireekan

Installation view of CLAUDIO PARMIGGIANI

“Melancholia,” at the Boghossian Foundation's Villa Empain in Brussels, arose out of curator Louma Salamé’s desire to take on the legacy of “Mélancolie,” which opened in Paris's Grand Palais in 2005. While the original show offered a cultural history of melancholy in the West, from the Middle Ages to modernity, the Brussels iteration promised to expand this exploration to include artists from around the world.

“Melancholia” offers a narrower interpretation of this state of mind, defined in the curatorial statement, somewhat fatalistically, as a reaction to the loss of past worlds. Divided into six sections—“Lost Paradise,” “Melancholia,” “Ruins,” “Passing Time,” “Solitude” and “Absence”—the show interestingly grounds this feeling largely in specific spatial and temporal terms. This compartmentalization is heightened by the arrangement of sections within discrete locations in the villa, leading visitors to relate the exhibition’s themes to the space, the Art Deco architecture of which enhanced the sense of decadence and decay.

Entering “Lost Paradise,” visitors first encounter Claudio Parmiggiani’s untitled 2013–15 installation, a big pile of severed heads from plaster reproductions of Classical statues scattered on the floor, which may remind poetry lovers of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” exploring the ravages of time on legacies of long-dead figures. Presented on the same floor was Pascal Convert’s Falaise de Bâmiyân (“Cliff of Bamiyan”) (2017), a breathtaking photographic series depicting the site of monumental Buddha statues in the Bamiyan valley of Afghanistan, destroyed in 2001 by the Taliban; as well as Convert’s evocation of libraries set on fire by authoritarian regimes, Bibliothèque (2016), an installation featuring more than 500 burned books, their remnants crystallized in glass. It is curious that Convert’s works fall in this section, as the “paradises” he captures have not been “lost” but taken by oppressive political forces.

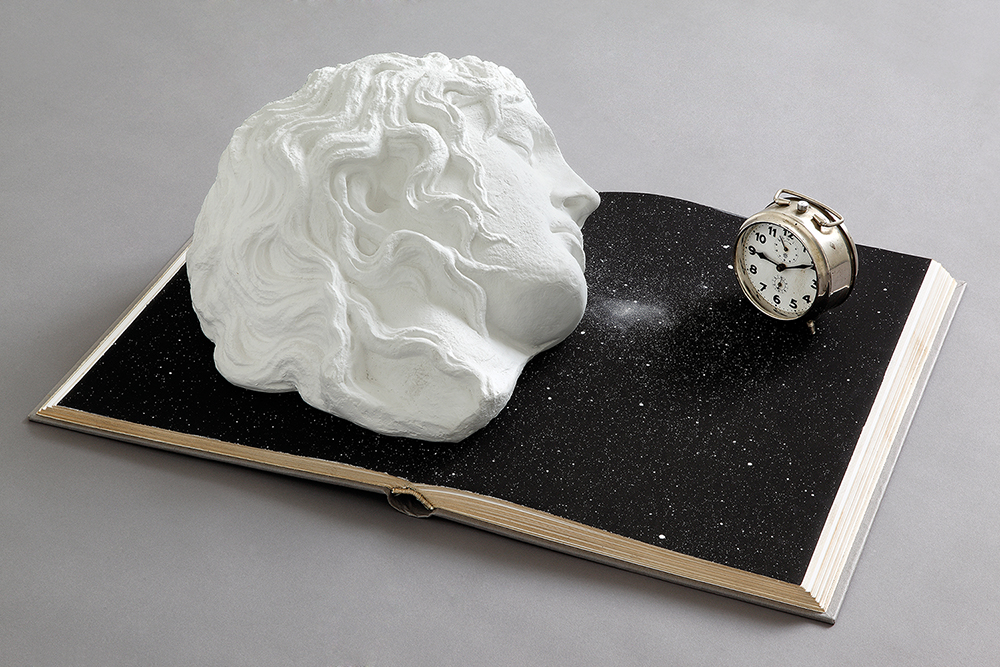

Skimming past these political complexities, the show returns to its central theme in an untitled 2009 installation by Parmiggiani on the second floor, composed of a head fragment of a reproduction Classical statue with closed eyes, placed alongside a clock on the open pages of a black book. While the book symbolizes knowledge, its black pages, sprinkled with what looks like a silver cloud of interstellar dust, represent the universe—an easily executed installation, yet effective in its metaphysical exploration of this affliction, which, Parmiggiani suggests, pivots on the interplay between space, time and knowledge.

Installation view of CLAUDIO PARMIGGIANI

This idea is poetically explored in On Kawara’s sound installation One Million Years (Past and Future) (1969–2000) and Lionel Estéve’s La Beauté d’une Cicatrice (“The Beauty of a Scar”) (2012). In the former, alternating male and female voices recount dates from 998.031 BC to 1.001.980 AD, reminding visitors of their colossally insignificant place in such a vast expanse of time, while Estéve’s beautifully assembled rocks from a beach in Greece, tinged a faint purple to imitate the marks left by receded water, are a testimony to change.

Despite the exhibition’s aim to expand its geographical and cultural remit, it included a mere seven artists (out of a total 35) who originate from and/or practice outside of the West. There seemed to be tension between the show’s framing of melancholy in universal terms and its stated goal of investigating representations of this affliction across cultures, resulting in a show that

lacked serious engagement with the cultural specificities of non-European conceptions. For example, although Franco-Belgian-Syrian artist Farah Atassi’s Still Life with Metronome (2016) and Woman in Profile (2017) were annotated as subversions of Western genres of still life and portraiture respectively, with their Arabian and Egyptian references, this so-called disruption of Western ideas is still both visually and conceptually reliant on Western tropes around melancholy rather than reflective of a culturally specific artistic endeavor. The same can be said of Melik Ohanian’s photograph of a desolate island, Selected Recording No. 99 (2003). Notable exceptions are Manal al-Dowayan’s Landscape of the Mind II (2009)—whose engagement with memory and identity examines the roles of Saudi women—and the trompe l’oeil watercolor portrait Tête (1985) by the late Marwan, whose brilliant problematization of Arabic calligraphy hovers between calligraphic mutation and the subtlest figural suggestion.

Furthermore, the show’s coupling of melancholia with “the problems facing humanity today” risks aestheticizing political conflict. Rendering dangerous political forces responsible for such grand-scale destruction as seen in Convert’s Falaise de Bâmiyân as “unavoidable” depoliticizes any action for resistance and change. The same applies to the show’s framing of Jef Geys’s beautiful scroll !vrouwenvragen? (“!women’s questions?”) (1964–2007), where questions posed by women who had spotted social injustice are, in the context of the show, explained as constitutive of the heavy-headed condition of melancholia.

Although the show homed in on the universal and metaphysical dimensions of melancholia, it could have benefited from thinking more about the specificities of the cultural production of this notion, and the political agency of artworks under such an intercultural framing.

“Melancholia” is on view at the Villa Empain, Brussels, until August 19, 2018.