Korakrit Arunanondchai’s “nostalgia for unity”

By Kamori Osthananda

Installation view of KORAKRIT ARUNANONDCHAI’s nostalgia for unity, 2024, immersive installation with imageless film and carbon-embedded ground, at the Bangkok Kunsthalle. Courtesy Bangkok Kunsthalle.

Korakrit Arunanondchai

nostalgia for unity

Bangkok Kunsthalle

Bangkok

May 31–Oct 31

A cavernous, chamber-like structure eclipsed by traces of black soot and nebulous amber haze stood wide open. Within the immersive work, titled nostalgia for unity (2024), an omnipresent, atmospheric chant echoed throughout the abandoned space of what was once a publishing house. Dried earth that appeared ancient and sacred covered the floor, with every crevice of the substance seeming at the brink of a chasm. Traversing across it, glimpses of imprinted words came to view, such as “after death” and “World.” The words were fragmented by sporadic light, frustrating and overwhelming the senses. But this confusion was part of a larger process to realize Korakrit Arunanondchai’s nostalgia for unity as a whole, for the meditative installation facilitated the momentary passing of meaning in its entirety.

Arunanondchai’s use of language as imagery is reminiscent of ancient burial grounds and tombs as, historically, polytheistic beliefs regarded the possibility of the afterlife through language. This spirituality ties into the legacy of the exhibition space: a former printing house, Watana Panich used to serve as Thailand’s foremost academic publisher. However, the space was abandoned after a fire consumed it roughly 20 years ago, causing significant infrastructural damage. In January this brutalist building in Bangkok’s Chinatown district was reclaimed as an art space, and for nostalgia for unity Arunanondchai allowed language to be a medium in commemorating this history.

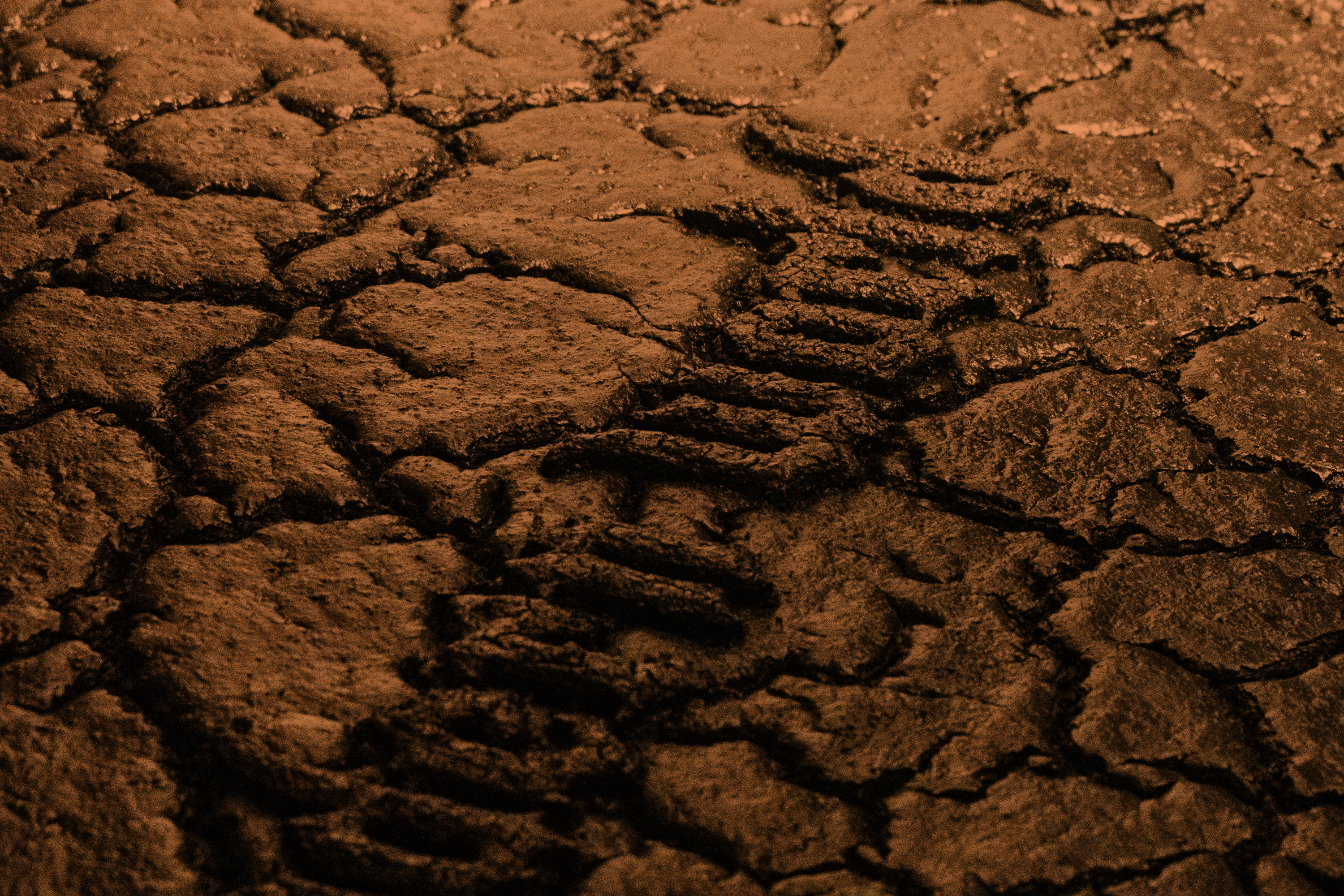

Detail of KORAKRIT ARUNANONDCHAI’s nostalgia for unity, 2024, immersive installation with imageless film and carbon-embedded ground, at the Bangkok Kunsthalle. Courtesy Bangkok Kunsthalle.

Within the installation, carbon—a chemical element often present in war, extraction, and the depletion of natural resources—was embedded in the dark, artificial substance constituting the raised earth that viewers walked upon. Yet, despite its negative colonial connotations, carbon is also created from the burning of joss sticks and incense in acts of religious and spiritual worship. Accordingly, Arunanondchai’s imprinted language of fragmented prayers was born from an element that conjures both the vast misfortunes of human society and ceremonial incantation. The floor also contained clay, a quintessential material in Thai amulets and votive tablets. Within this carbon-embedded, clay-mixed ground, deep cracks offered viewers a look into the void: inspecting the broken earth surrounded by pieces of man-made stories, one found nothing but more darkness.

Meanwhile, the haze, which was as luminous as the flicker of a candle, revealed the room’s formidable church-like architecture. The atmosphere of its structure resembled what Thai and Southeast Asian peoples may regard as a “potent place,” a space activated through human interaction that captures the personality, fate, and fortune of dwellers and passersby’s in its walls, air, and ground. The installation’s elements of worship, animism, and impermanence are also evident in Thai Buddhism, although the imprinted prayers were neither written in Pali nor Sanskrit (the primary languages associated with the religion). Arunanondchai’s text in fact emulated the styles of Latin and Gothic scripture, which is associated with a different belief system entirely. As the contrast between these spiritual and material symbols—clay, carbon, lighting, scripture, chanting—are only apparent through different senses, the beauty of nostalgia in unity thus became how it functioned in different experiential realities.

Installation view of KORAKRIT ARUNANONDCHAI’s nostalgia for unity, 2024, immersive installation with imageless film and carbon-embedded ground, at the Bangkok Kunsthalle. Courtesy Bangkok Kunsthalle.

Ultimately, negative space acted as a through line in bringing these ambiguous elements together. Where one would typically expect the sight of ghosts and shamans at the mention of Arunanondchai’s name, the technoanimistic artist here facilitated a different kind of fire gathering, one that married religion, belief, and postcolonial issues. “In Korakrit’s practice, language is the tool to connect different dimensions of reality,” stated curators Stefano Rabolli Pansera, Mark Chearavanont, and Gemmica Sinthawalai. The artist indeed achieved this actualization through emptiness and time, as viewers were confronted with prayers left unread, unrealized, and oblivious to postcolonial realities. Read another way, an unread prayer was a negative space within language; shadows functioned as a negative space of light; oblivion was a negative space in nostalgia. Akin to a Greco-Roman hero in classical antiquity viewing life as a vehicle to defeat death’s oblivion, Arunanondchai’s prayers, like scripture, expanded and shrunk themselves according to the semantics of existence. Through his installation, then, Arunanondchai invited viewers to rid their notions of life and death and embrace them as essential, mutually dependent stages.

Kamori Osthananda is a Bangkok-based art writer.