What Would a Memorial to the Partition Look Like?

By Alexandra Chaves

%20(1).jpg)

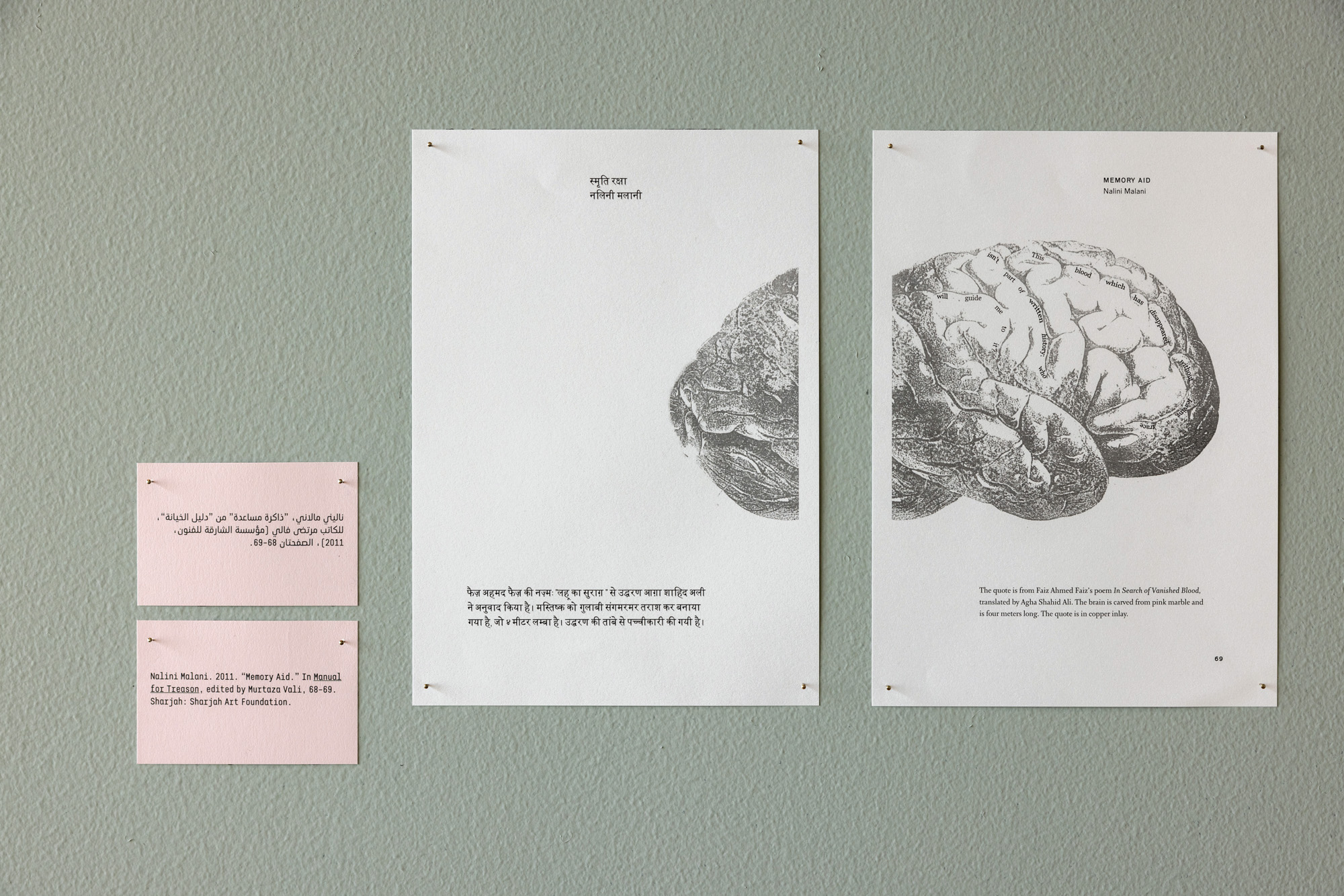

NALINI MALANI’s proposal Memory Aid (2011), included as a part of the book Manual for Treason (2011), edited by Murtaza Vali and published for the Sharjah Biennial 10. Installation view at "Proposals for a Memorial to Partition," Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, 2021-22. Photo by Daniella Bapista. Courtesy Art Jameel, Dubai.

Memorials to the partition of India are scant. Decades after the subcontinent’s cleaving by British colonizers in 1947, neither Pakistan nor India have built public monuments that commemorate the displacement and deaths that followed. The closest thing to a monument, perhaps, is the Partition Museum in Amritsar. Snippets of the Museum’s audio guide, recorded secretly by artist collective CAMP, are broadcasted through the motion-activated speakers in their installation You Are Now (2022), which were hidden and scattered across the group show “Proposals for a Memorial to Partition” at Jameel Arts Centre, creating disorientation with hints at ghosts or imaginings. This sense of incompleteness extended throughout the show, as intended by the curator Murtaza Vali: “It is preliminary, speculative, tentative, a suggestion, something put forth . . . This exploratory nature of the proposal is key.”

An idea originated from Vali’s book Manual for Treason (2011) published for the Sharjah Biennial 10, “Proposals” featured videos and installations by 20 artists of different generations and places in South Asia, including a few who contributed to the book. The show tackled questions around memory, such as “What is kept and sanctified? What is discarded in the aftermath of a historical trauma?” while weighing the consequences of nation-building on people and place.

.jpg)

Detail of SHILPA GUPTA’s Untitled, 2022, pinewood, 18 × 18 × 148 cm, at "Proposals for a Memorial to Partition," Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, 2021-22. Photo by Daniella Bapista. Courtesy the artist and Art Jameel, Dubai.

Satire runs through some works, as in Shilpa Gupta’s untitled proposal, which comprises maquettes made from deconstructed national flags, stacked to form a scale model for a larger monument. Yet the artist has rendered them as building block toys, mocking patriotic sentiments. Pak Khawateen Painting Club (Urdu for “Pure Pakistani Women’s Painting Club”) proposed a fictional state project for a Partition Museum in Pakistan, which features a desk heaped with folders of paperwork. On the papers are architectural plans, official correspondences between government departments detailing the bureaucratic procedures, and even an invitation to Queen Elizabeth II for the official opening.

.jpg)

Installation view of PAK KHAWATEEN PAINTING CLUB‘s The Case of Pak Khawateen Painting Club’s Proposed Museum, 2022, mixed-media installation, dimensions variable, at "Proposals for a Memorial to Partition," Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, 2021-22. Photo by Daniella Bapista. Courtesy the artists and Art Jameel, Dubai.

In the center of one gallery was Fazal Rizvi’s These winds that are etched in our bones (2022), a meditative installation constructed as a place of worship with its layered carpets akin to prayer rugs. The work comes to life with the sound of the human breath that shifts from labored breathing to howling winds. Rizvi forgoes symbols of nation and commemoration, and instead hones in on the emotional and invisible—the bodily experience of remembering. Unlike most public monuments, it exemplifies what Vali wrote: “Trauma resists representation.”

%20copy.jpg)

FAZAL RIZVI, These winds that are etched in our bones, 2022, four-channel audio installation, carpets, wooden table, and publication, dimensions variable, sound piece: 10 min 28 sec, at "Proposals for a Memorial to Partition," Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, 2021-22. Photo by Daniella Bapista. Courtesy the artist; Grey Noise, Dubai; and Art Jameel, Dubai.

The effects of trauma also lead to illusion and idealism, as in Bani Abidi’s two video works, which were created more than 20 years apart but displayed side by side. In Mangoes (2000), the artist plays two young women, one Indian and the other Pakistani, praising their country’s varieties of mango. What begins as a shared enjoyment quickly turns into a competition between the nations. In the subsequent Mother Lands (2022) the work plays out like a home video: two older women address the camera to talk to their son Mir, a young half-Indian, half-Pakistani boy who grows up between the two countries and Germany. Both played by Abidi, the women speak of borders and divisions: “Sadly as you grow, you’ll witness that there’s so much hatred and violence between people.” They describe their son as a “walking, talking monument” that embodies both unity and borderless state.

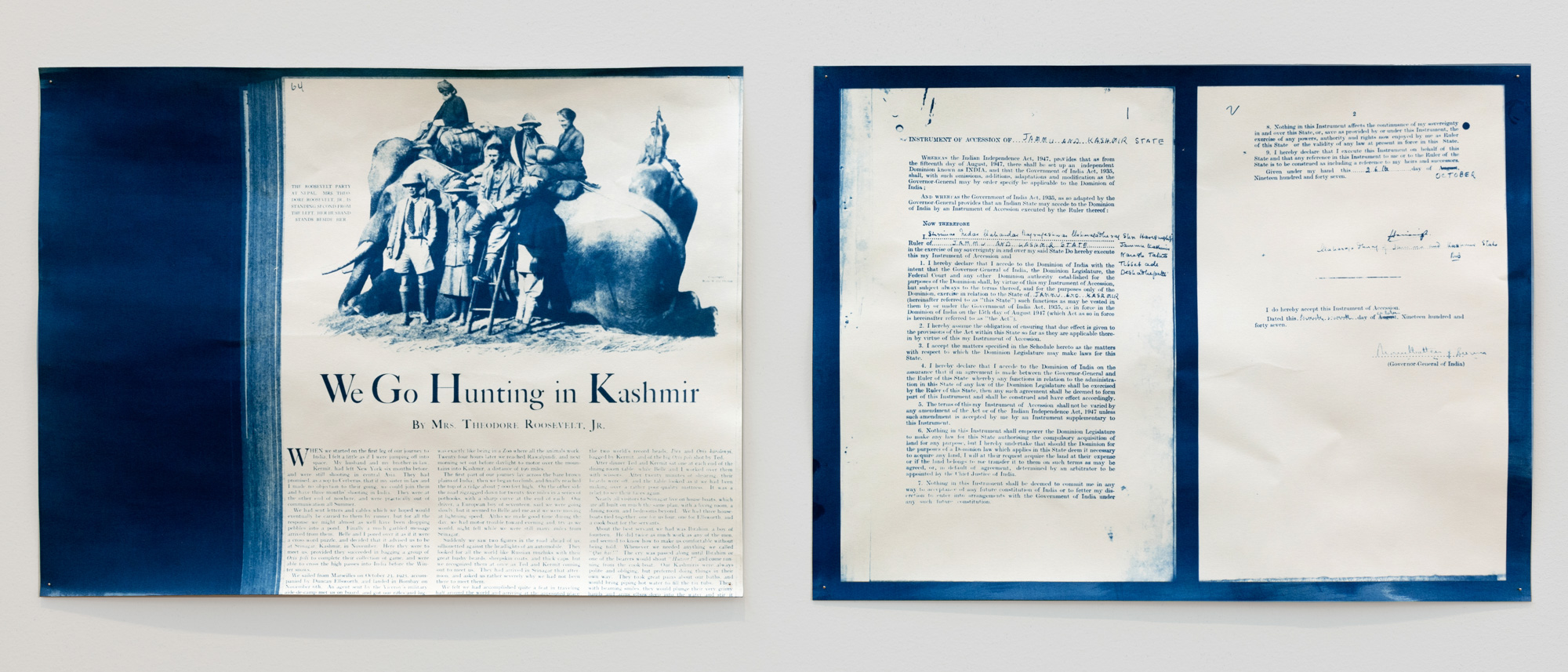

Abidi’s work, though laced with warm humor and familial love, also bears a sense of detachment afforded by distance. This reverberates in parts of the show, which Vali describes as seeking to find “a collective gesture towards excavating the traumatic underbelly of nation-building in the Subcontinent.” But legacies of the division persist on the streets in South Asia, with religious mobs and border conflict. Nabla Yahya’s Silsila (2022) explores these ongoing brutalities and their colonial linkages in the form of cyanotypes. The prints focus on documents related to Kashmir, including Dogra gold coins that are now in the British Museum’s collection and an x-ray of a young girl’s skull repeatedly struck by pellets of the Indian police.

.jpg)

Installation view of NABLA YAHYA’s Silsila, 2022, cyanotypes on paper, dimensions variable, at "Proposals for a Memorial to Partition," Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, 2021-22. Photo by Daniella Bapista. Courtesy the artist and Art Jameel, Dubai.

Perhaps this is why public monuments for Partition have been so few in number: a monument indicates an ending, a form of judicial resolution, or a collective agreement on narrative—none of which exist. Proposals hints at the political, but leaps into the contemplative. While the show deftly navigated this thorny history, it resigned to its own futility, with artists’ proposals more involved in reflection than resolution.

“Proposals for a Memorial to Partition” is on view at Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, through February 19, 2023.