Wei-Chieh Kung and Lydia Ya Chu Chang’s Blue House

By Annette An-Jen Liu

WEI-CHIEH KUNG and LYDIA YA CHU CHANG’s Blue House, 2022, timber, at the TFAM Plaza, Taiwan. Photo by Annette An-Jen Liu. All images courtesy the artists and TFAM, Taipei.

Since late May, a peculiar, blue-gray construction has occupied the plaza outside the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM). The wooden architecture’s elegant, undulating floor stretches across two sets of steps and three landings. This is Blue House, the 2022 X-site laureate, conceived by Taiwanese artists Wei-Chieh Kung and Lydia Ya Chu Chang for TFAM’s annual public-art open call.

Inside, exposed pine rafters frame a large, triangular opening in the ceiling and make way for a smaller, circular aperture. Light casts through these shapes, illuminating the interior’s blue coating. A gap is left between the eaves and the floor, and without side walls, the sloping roof doesn’t enclose the space, creating strips of asymmetrical openings along the ground that allow one to spy in from outside, or peek out from within.

A playful and unassuming dwelling where one can rest and hide, Blue House (2022) has a whimsical quality, like that of a tree house. The structure offers shade and shelter from the humid Taipei summer, becoming a place of repose and a site for imagination. Kung and Chang, who both come from architectural backgrounds, define Blue House vaguely. “Blue House could be home,” Kung describes, “[It] could also be weight, compromise, paper folding . . . a raindrop, cave, page number, or fishing.” Similarly, Chang expresses that the house may be “an entrance to a boundless ocean or forest,” as well as a “container full of events.”

These ambiguous definitions ground the series of accompanying public programs called “Blue House Study.” Curated by Kung and Chang in collaboration with other Taiwanese artists, the events are informed by the five senses, creating new ways of experiencing Blue House that facilitate “multiple [readings] of immediacy.”

.jpg)

WEI-CHIEH KUNG and LYDIA YA CHU CHANG, Blue Nose: Being There, 2022, fragrance, glass, rubber tubes, dimensions variable, as part of the Blue House Study at Blue House, TFAM Plaza. Photo by Lydia Chang.

Blue Nose (2022) was a two-week olfactory installation designed with artist Pao-Leng Kung and aromatherapists Melvin Chen and Raymond Tang. Two bespoke fragrances were stored inside nine elaborate devices made of glass tubes and rubber pipes that were placed around Blue House—on the floor, under the roof, on a beam. The perfumes were diffused subtly and slowly from the canisters, which were designed to limit the spread of the scent. One had to lean in to smell the dewy, zesty blends—an engagement that was unclear without the museum staff’s prompt. Nonetheless, Blue Nose encouraged a closer examination of its surrounding space.

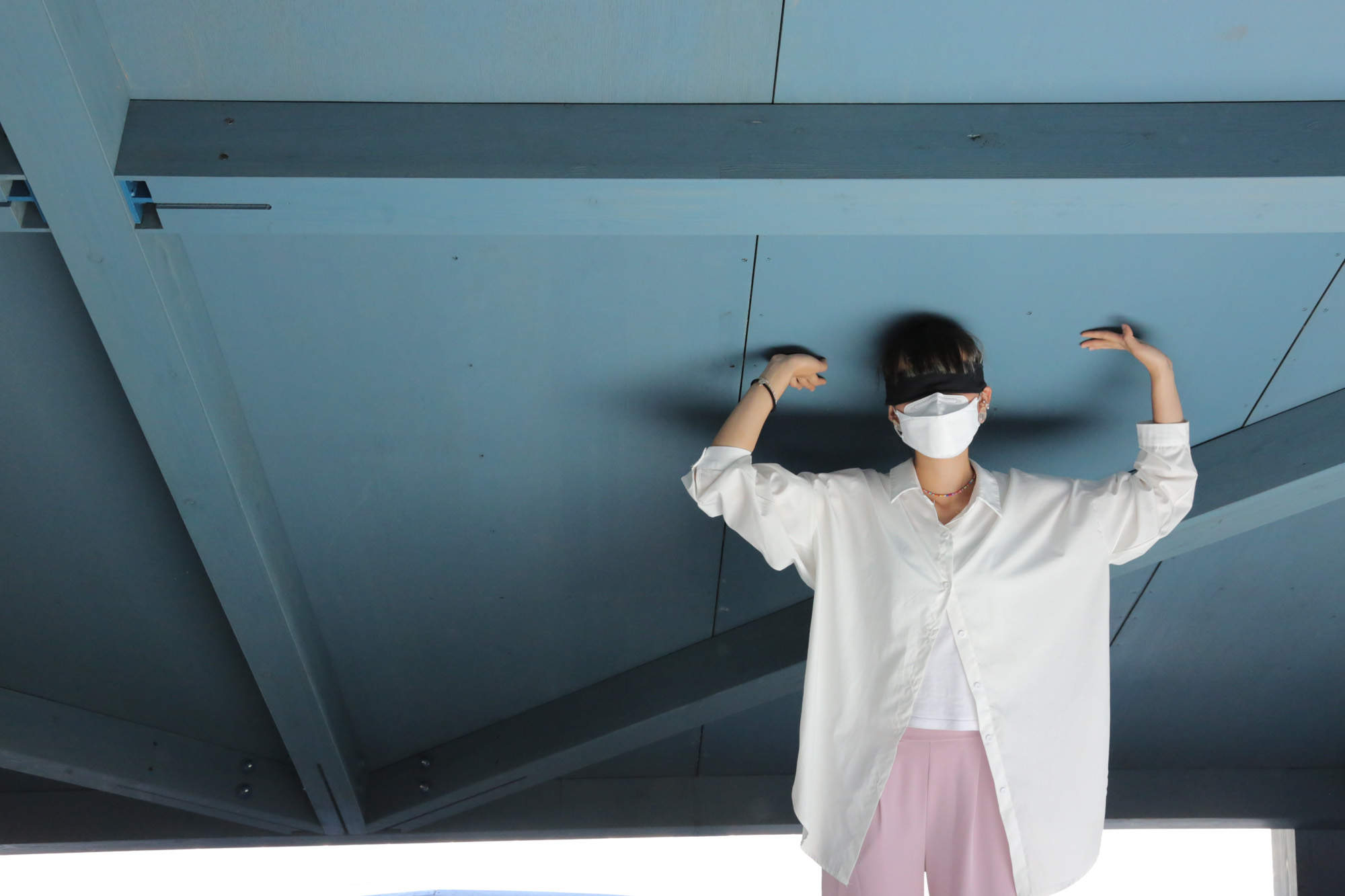

WEI-CHIEH KUNG and LYDIA YA CHU CHANG, "Blue Body: Spirit Song Over the Waters," 2022, 30-person workshop: 90 min, as part of the Blue House Study at Blue House, TFAM Plaza. Photo by Annette An-Jen Liu.

Stimulating more physically active forms of audience participation were the movement workshop “Blue Body” and the haptic sessions of “Blue Eyes.” “Blue Body” started out as a performance by dancer Chen Chen and musician Yi Fan-Chuang. Over the course of an hour, their choreography turned into collective play with guided participation. In three sequences, selected audience members were instructed to improvise gestures with a fabric sheet and painted masks. Watching Chen appoint the next person felt uneasy, but the anticipation and rotation of amateur performers steadily became something one looked forward to, perhaps voyeuristically. In these moments, Blue House transformed into a shared stage. One of the final scenes saw everyone participate by mimicking the movements of the appointed person. Hiding behind the anonymity of the masks, the leading participants seemed emboldened to move shamelessly: running, stomping, and dancing to music that grew louder and more upbeat. Laughter was shared across Blue House, turning the space into one of joyous gathering.

WEI-CHIEH KUNG and LYDIA YA CHU CHANG, "Blue Eyes: Inner Landscape," 2022, 24-person workshop: 80 min, as part of the Blue House Study at Blue House, TFAM Plaza. Photo by Lydia Chang.

In “Blue Eyes,” groups of blindfolded participants placed their hands on each other’s shoulders and were escorted around Blue House by visually impaired guides from the social business Dialogue in the Dark. The guides described the architecture’s various areas, and assisted each participant to reach out and feel their way around the space. For the visually nonimpaired, this haptic experience heightened sensitivity to sound and temperature. The volume of voices guided one’s careful and tentative navigation, and the textures of the space suddenly felt more protruding. Like “Blue Body,” this program required trust and a full commitment to the experience.

Public art projects come with their challenges, and hosting public programs requires even more consideration. The collaborative conception and execution of Blue House Study went through rounds of reviews and revisions. Despite these discussions and having precautions in place (such as additional staff, no after-hours access, and safety measures for typhoons), Blue House demonstrates the potential for public art initiatives to create surprising possibilities for—and from—thoughtful experimentation, enriching interactions, and new understandings of the environment around us.

Blue House is on view at the TFAM Plaza, Taipei, until July 31, 2022.