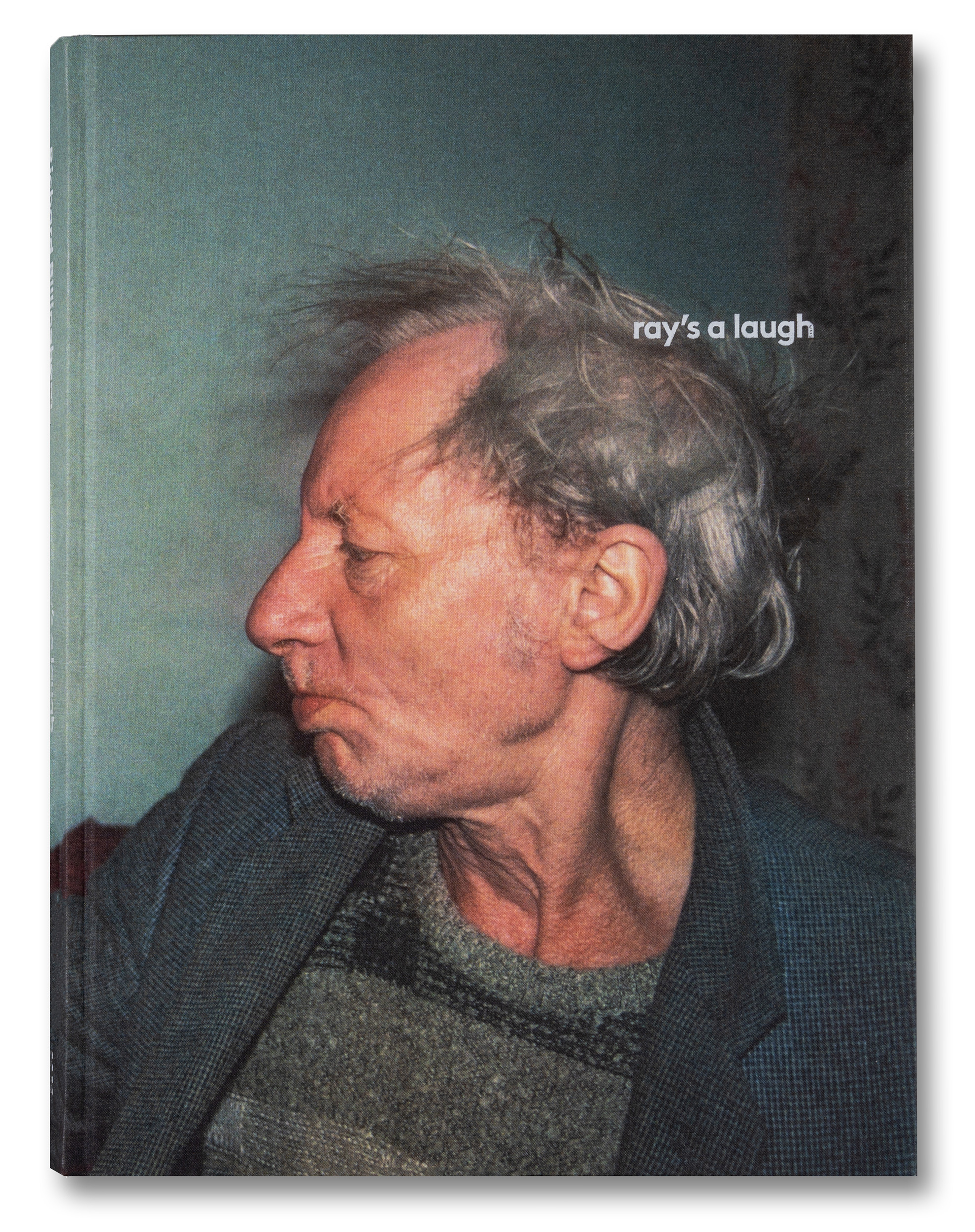

Tough Love in Richard Billingham’s “Ray’s a Laugh”

By OLIVER CLASPER

RICHARD BILLINGHAM, Ray’s a Laugh, published by Mack, London, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Mack.

Ray’s a Laugh

By Richard Billingham

Published by Mack

London, 2024

The first iteration of Ray’s a Laugh (1996/2024) was the result of a

strange and fortuitous journey. In the early 1990s, a young art student at the

University of Sunderland named Richard Billingham began photographing his

father, Ray, for the basis of early acrylic portraits on cardboard. Some were shot

in the Cradley Heath council flat where Billingham lived with his father; most

were taken after his mother Liz moved back into the flat following her earlier

separation from Ray. Also living there were several dogs and cats, as well as Billingham’s

younger brother Jason, who had at one time been in state care. According to

Billingham, the council estate was “a real ghetto”: shit and piss in the

stairwells, racist graffiti everywhere, broken windows, spit on the walls. To

make matters worse, Ray was an alcoholic. Over the course of a few years Billingham

recorded this caustic, majestic, mad, brutal, and strangely loving family

set-up in thousands of photographs, many taken on a cheap Zenit automatic

camera (he later used a more “professional” Nikon 35mm), many washed out by the

bright glare of the flash. But they were never meant for exhibition or

publication; Billingham simply wanted to document what he saw and experienced,

to capture what was unfolding around him—first to aid his paintings, later,

because it had become second nature. It was real life; a drama that, ironically

or not, was not all that dramatic.

That Billingham had his work published at all involved,

at various points, the art collector, dealer, and patron Charles Saatchi, as well as

established photographers Martin Parr and Paul Graham (Parr helped Billingham have a triptych of black-and-white portraits of his father included in a group show at the Barbican in 1994). During his studies,

Billingham had given a plastic bag stuffed full of his photos—many of them

crumpled, ripped, and splattered with paint from the studio—to a contact in

the art world via his university tutor, Julian Germain, and before he knew it his

work was being rushed into publication by Scalo with an epigraph by American

photographer Robert Frank. This was in 1996, and a short while later Saatchi acquired more of Billingham’s work for the

groundbreaking and infamous “Sensation”

exhibition in 1997 at the Royal Academy of Arts, alongside Damien

Hirst, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, Marc Quinn, and Jake and Dinos Chapman.

Last year, after close collaboration with Billingham, London-based publisher Mack

completely redesigned and reformatted Ray’s a Laugh, tripling the number

of photographs and jettisoning Scalo’s cheap and sensationalist marketing (where

Billingham and Germain had hoped for, and had reasonably expected, a gentler

approach, the Swiss publishers, much to Billingham’s disapproval, went with a garish

red cover that included a none-too-subtle blurred image of Ray, a somewhat

tone-deaf epigraph from Frank, and an overall mood that grossly overstated his

father’s alcoholism and his family’s dysfunction). In essence, Mack stripped it

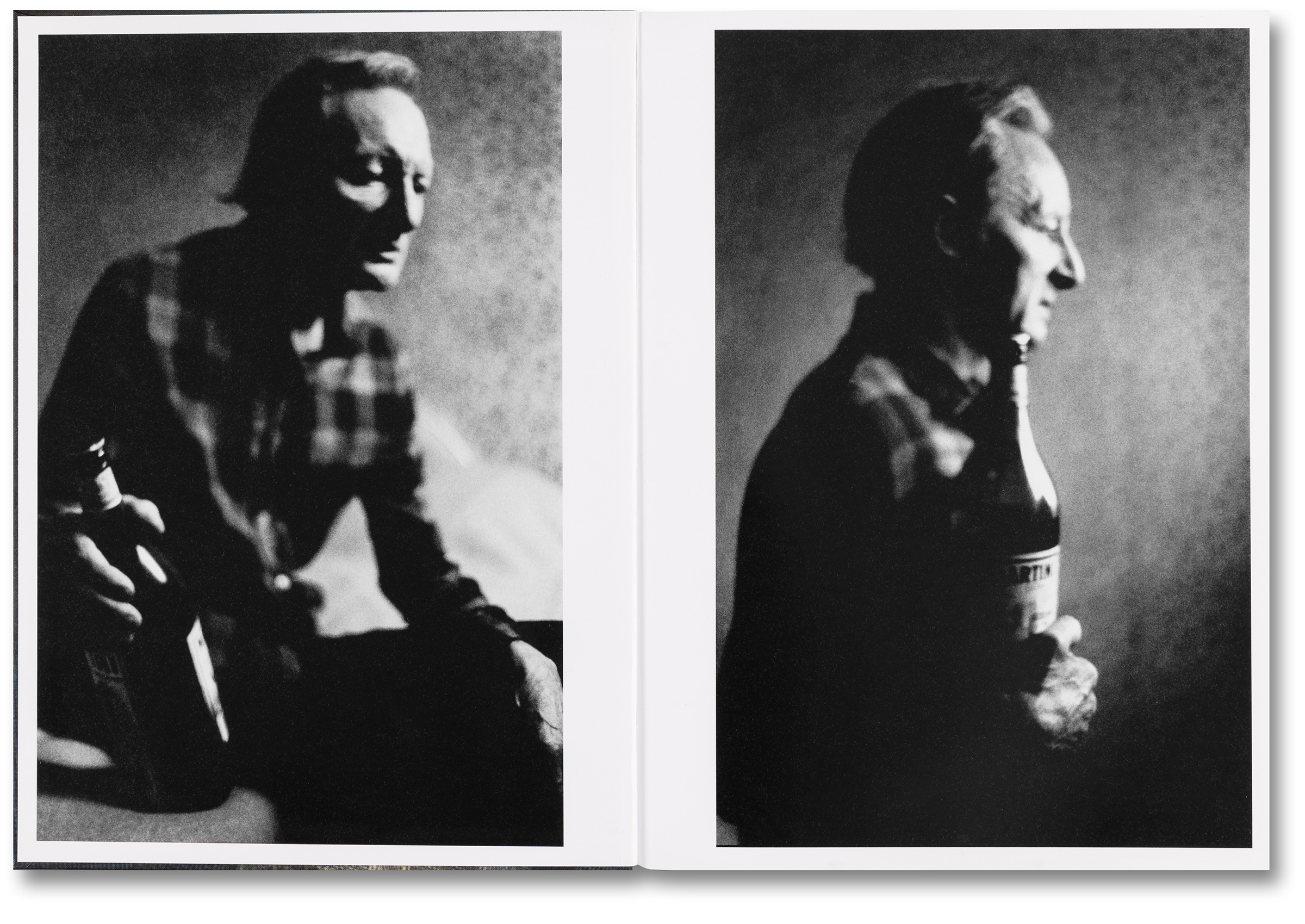

back to its roots. Where the Scalo book opens with an exterior of the

surrounding council blocks in color, the latest version opens with interiors: a

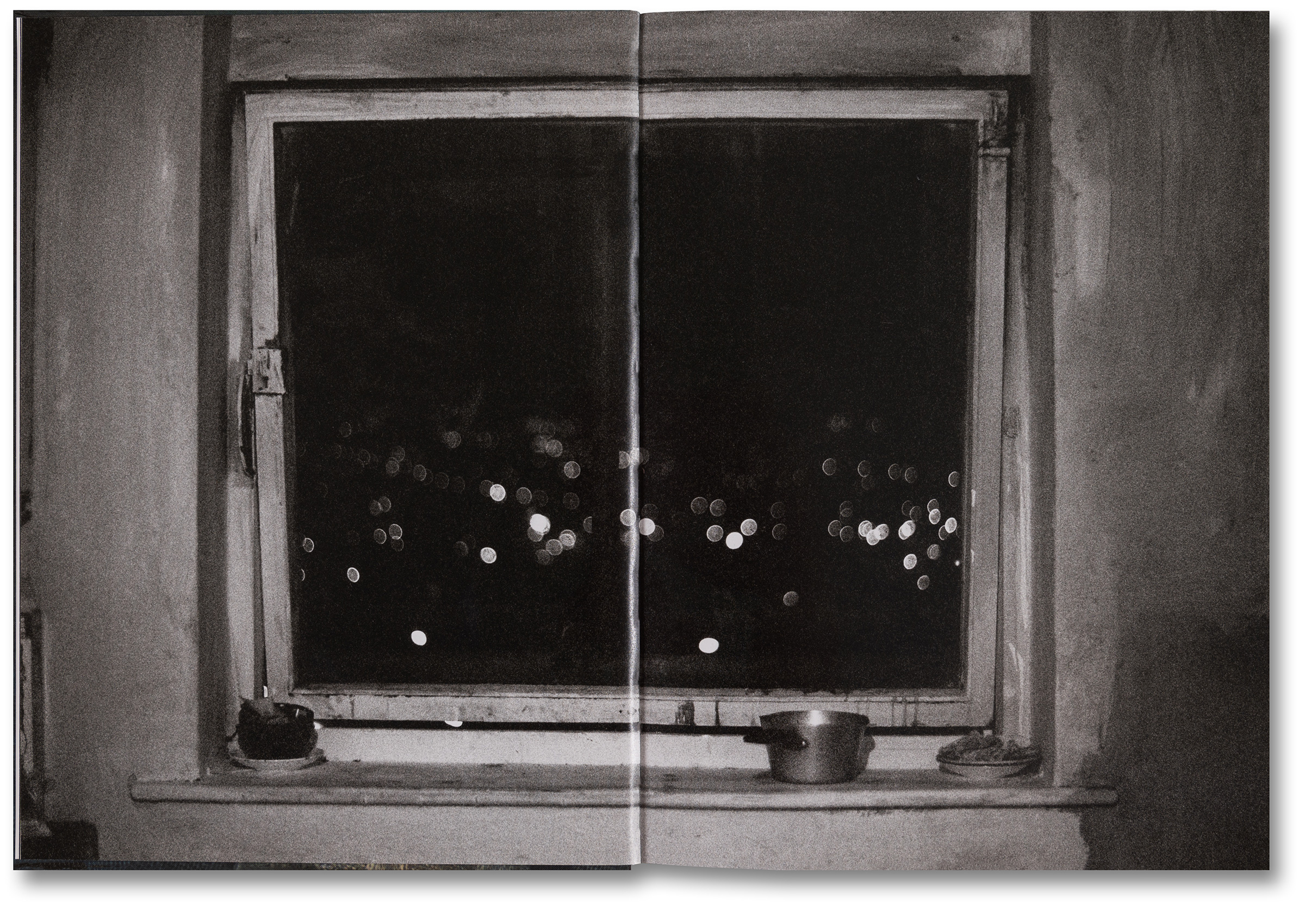

series of reflective, low-light, black-and-white portraits of Ray, sitting on

the edge of his bed holding a bottle of vermouth, followed by a close-up of a

wall and a window at night, most likely Ray’s point of view (how many hours Ray

must have sat and stared out into the gloomy Black Country night, pushing away the

demons). These photographs—compared to what follow, and certainly compared to

what most people think of when they picture Billingham’s iconic images—are

elegiac, somber, stately, universal. Ray’s thin, gray hair is combed back, he

wears a checked shirt hanging off his fragile frame, and in one image he sits

forward, no bottle, hands pressed gently together, in contemplation, or perhaps

in prayer.

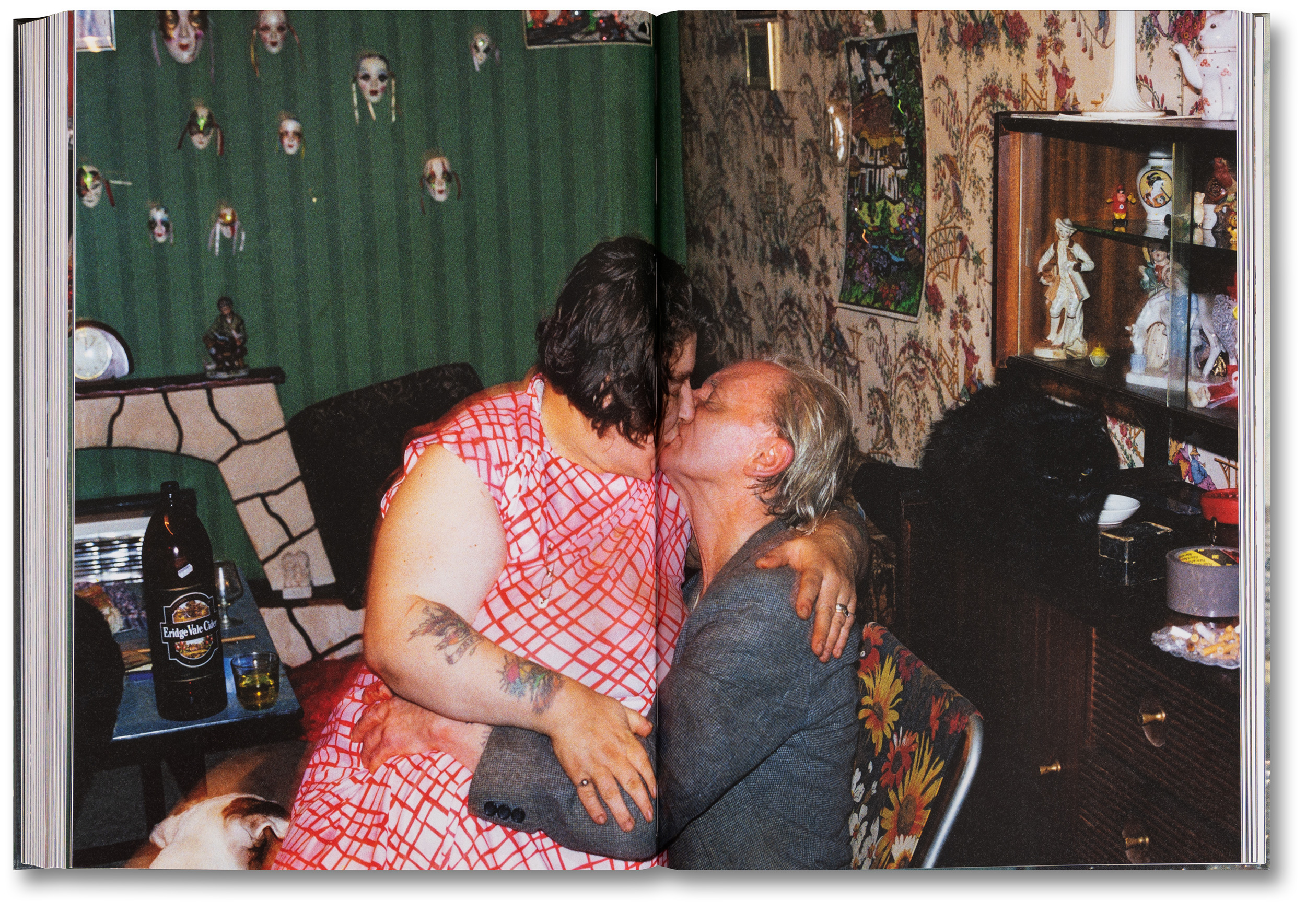

Image after image, a relentless cornucopia, a barrage, a riot, no, a

celebration of the chaotic, maddening life Ray shared with his wife and two

sons. As David Wise writes in Mack’s accompanying paperback, Ray’s a Laugh:

A Reader (2024): “Ray as Everyman who has ever been down on his knees,

confounded by the meaning of things. A scene Beckett would have understood.” Billingham

even once told an interviewer that every day he used to come home from college and

wonder whether he’d find his father dead or alive, and over the years a number

of critics have tried to decipher Billingham’s work as being spiteful, vengeful,

even Oedipal, which he has vehemently denied (“They like what I do. I want them

to see everything.”); for him, it was an act of devotion, or a tribute, of

sorts. And it’s easy to see why, despite the aggression and the intrusion and

the exposition of so many unadulterated, private moments: Ray in the midst of

falling over; Ray and Liz eating a TV dinner, gravy dripping down their front;

Ray slumped on the bathroom floor, the toilet bowl caked in vomit; Ray with a

bloody nose, the aftermath of a fistfight with Liz; Ray, later, stalking toward

Liz, fist clenched, no match for her, evidently (she’s over twice his size, and

fearsome, hardy, no-nonsense); Ray throwing the family cat across the room

toward the camera; Billingham’s troubled younger brother looking lost in front

of a table scattered with weed.

Interspersed with all this violence and disorder and claustrophobic rapture are

photographs of an old man dealing with the realities of severe alcohol abuse, a

stark record of that horrific disease: Ray eyeing up bottles of alcohol, then

staring forlornly out of the same window. Ray laughing, and laughing loud, so

hard we can hear it through the printed page. Elsewhere, Liz makes a birthday cake

onto which someone (Jason?) has drawn a hairy cock and balls in icing sugar;

and Liz completes a large jigsaw puzzle, the pattern of which, remarkably,

matches her blouse; the cats and dogs lounge around, licking their genitals;

and, most poignantly of all, Ray and Liz hugging, reconciling, making peace

with each other and the world.

Ray's a Laugh also manifests as both a universal undertaking and a distinctly parochial one: it’s in the fittings and in the furniture, in the products and brand names familiar to those of us who grew up in England in the 1990s. A specifically working-class milieu to be sure, but not all that far from how many of us saw our own grandparents at that time, in particular those men who had fought in the war, who smoked and drank themselves to death, who argued with their spouses, belittled their children (especially their daughters), and lived in dark and musty rooms in dreary commuter towns. In Billingham’s recognizable images we bear witness to the full panoply of lives lived: ordinary, complicated lives, nuanced existences, shades of gray. In a 1997 essay published in Artforum that is also included in Ray’s a Laugh: A Reader, Jim Lewis wrote that “what makes some photographs great is precisely the balance they strike between devouring their subject and adoring it, and the surprise they inspire at the idea that whatever they’re picturing can bear the weight of just that contradiction.”

French poet and essayist Paul Valéry once remarked that bad poetry “vanishes

into meaning.” And so rather than attempt some futile psychological

deconstruction of Billingham or his photographs, we simply look. And once

we’ve looked, we admire. Admire the audacity and the bravery, admire the

madness and the misdirection, admire the skill and the accident. And finally, we

might realize, after all, that perhaps this grand flux of images, this

concentration of cinematic prose, is nothing more beautiful or more profound

than a simple act of love.

Oliver Clasper is the managing editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

Subscribe

to ArtAsiaPacific’s free weekly newsletter with all the latest news,

reviews, and perspectives, directly to your inbox each Monday.