The sexuality of “Stargazing”

By Avni Doshi

JAISHRI ABICHANDANI, Klingon as Self, 2012, photo, 28 × 35.3 cm. Courtesy Rossi & Rossi, London.

In a recent show at Rossi & Rossi in London, artist and curator Jaishri Abichandani brought together the work of five artists, including herself, in a discussion about the ways popular imagination and fact surrounding the act of looking up at the night sky come together to shape sexual identity. The idea of stargazing, she says in the catalogue essay, “is understood as the absorption in chimerical or impractical ideas.” By pursuing the boundaries where fact becomes science fiction, Abichandani’s “Stargazing,” searches for the outliers, anomalies and bodies that fall beyond the reach of normative heterosexuality.

Abichandani's own photos playfully incorporate self-portraiture in images of characters from the popular television series Star Trek. The characters in the television show age differently than people and operate within a different spectrum of sexuality. Desexualized in some ways, the portraits reference a change in the artist’s understanding of her body and sexuality in relation to age, childbirth and motherhood. In Klingon as Self (2012), Abichandani superimposes her own image on that of an extraterrestrial male warrior. With long hair, a stylized beard and muscular build, the artist’s own individuality is clouded within the stereotypical image of the Klingon soldier. Klingons are not supposed to be driven by personal desire, but instead give themselves up to the greater good of the community. By combining her own image with that of an unquestioning soldier, Abichandani raises questions about how her own role within society has altered since becoming a mother. While giving birth is in some ways the most obvious reflection of a woman's sexual life, is it also the conclusion of her perception of herself as a sexual being? If not, how then does a woman formulate her sexual identity? The self-portraits reflect these questions as well as an intense longing to be recognized as a multifaceted sexual being.

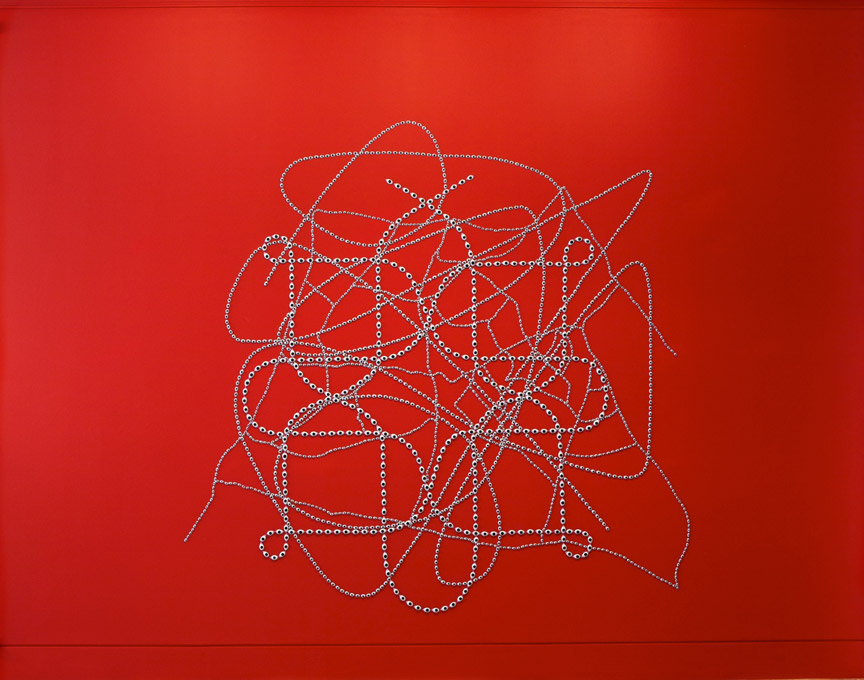

ANITA DUBE, Neti Neti, 2009, found votive glass eyes on painted wall, 250 × 250 cm. Courtesy Rossi & Rossi, London.

The title of Anita Dube's work, Neti Neti (2009), literally translates into "neither, nor" and refers to an ancient Hindu chant which describes the universe not by what it is, but by what it is not. The work, a maze-like constellation of enamel eyes, opens up a grid suggestive of omnipotence. The idea of a description which cannot actually describe but can only fill in the surrounding gaps of negative space, suggests the impossibility of a definitive identity, sexual or otherwise.

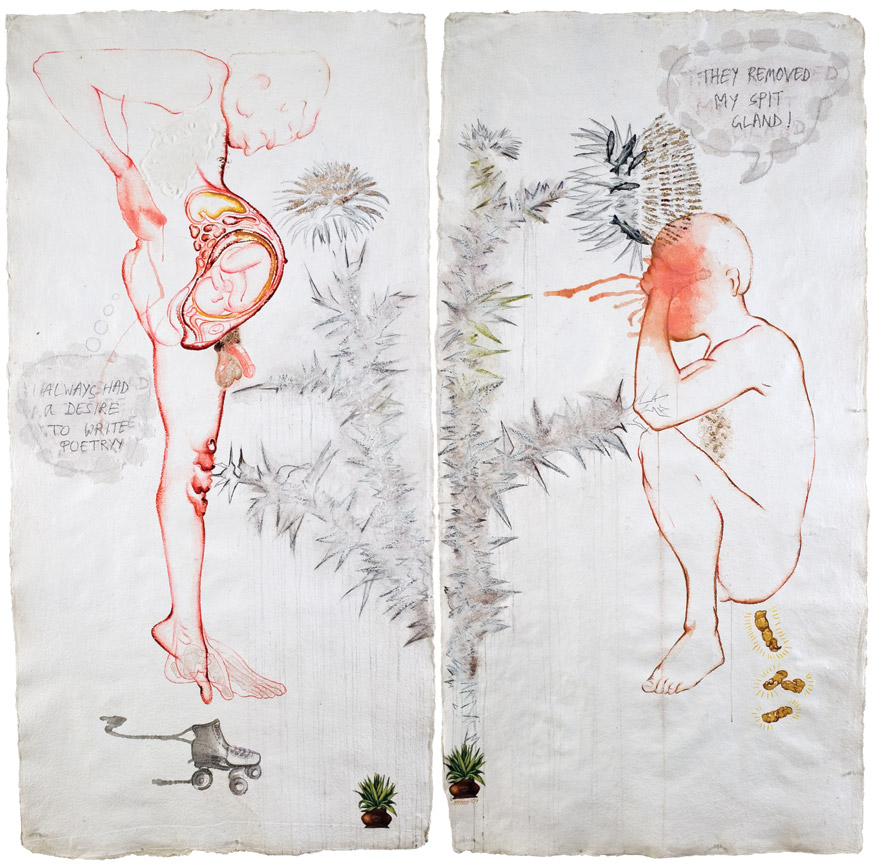

MITHU SEN, You Owe Me!, 2009, mixed media on handmade paper, 211 × 107 cm. Courtesy Rossi & Rossi, London.

Mithu Sen's mixed-media drawings identify male sexual anxiety. Her work conjures shame and confusion surrounding the male body, and its desire to be a controlled and fortified form. Sen places her protagonists in embarrassing and potentially nightmarish situations. In one drawing, from a pair titled You Owe Me! (2009), a man looks down at his penis only to find a pregnant belly in the way. In the other drawing, he defecates on the ground while sobbing.

Chitra Ganesh's large prints echo the form of popular graphic novels famous in India for illustrating religious stories, with their flat and brightly colored images and simple textual explanations. Ganesh’s narratives, however, undermine this popular form by including myths from various cultures along with her own interpretations of dreams and literature. In Melancholia (Mask of Red Death) (2011), a multi-breasted celestial deity births dozens of skeletal creatures from her mouth, which crowd the starry sky. In turn, one of the skeletons has begun to devour the deity’s leg. Ominous text reading in part, “She, a garbage picker whose future is our past. And eyes that rip black holes from which our secrets fall,” both explain and confound the imagery. The imaginary celestial beings are depicted in pain, miserable and enslaved in their bodies. Instead of bounty, they are surrounded with decay. Both the words and imagery seem to suggest a terrifying cycle of birth and death, in which the female body is objectified and consumed.

A particularly surprising departure in “Stargazing” can be found in Nida Abidi's video Weatherproof (2011), which is perhaps the most candidly and unabashedly hopeful of the group. Her video shows a veiled woman transformed into a space traveler, blasted into outer space. With its flat, primary-colored penciled lines, the visual language of the piece is decidedly childlike. Abidi’s fantastical narrative emphasizes potency rather than limitations. The character’s hijab morphs into multiple forms, taking on the shape of a condom, and even a helicopter that propells her in the air. The artist uses humor, sexually suggestive imagery along with the fantastical story to subvert the notion of oppression traditionally associated with the veil.

While this exhibition is a part of an ongoing conversation on the slippery parameters of gender and sexual identity, each participating artist brings their own individual questions about otherness to the forefront. For Abichandani, curating this show was an attempt to further investigate the story of the other, which she explored in previous curatorial endeavors, including the group show of Iranian diaspora artists, “Shapeshifters and Aliens,” in 2011. The notion of the alien or unknown being provides a powerful metaphor for the experience of the outsider. By drawing from mythological and otherworldly themes, Abichandani lends otherness an oft-ignored sense of grandeur and awe. Not belonging, in this instance, becomes a space of imagination and transformation, ripe with possibilities.