Smoke, Smog, and Opaque Socio-Politics in the Indian Subcontinent

By Alessandra Alliata Nobili

.jpg)

Detail of PALA POTHUPITIYE’s Kokkilai, 2017, printed map, ink and pencil on paper, 91 × 66 cm. Courtesy the artist.

“HAZE – Contemporary Art From South Asia” was the inaugural exhibition of Fondazione Elpis’s new headquarters in Milan, located in a former 19th century industrial laundry. Interpreting the concept of haze in a metaphorical sense, Goa-based curators Mario D’Souza and the collective HH Art Spaces (comprised of Romain Loustau, Madhavi Gore, Nikhil Chopra, Shivani Gupta, and Shaira Sequeira Shetty) gathered works by 21 artists active in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh that delved into the opaque politics of the subcontinent and the socio-political turmoil now exacerbated by climate crisis.

Welcoming visitors was a wall-sized charcoal drawing of a barren seascape under a sky dotted with hazy, airy clouds. Towering in the foreground is a conical rock, caressed by amicable waves on the deserted beach. Titled The rock needs no water and the island never cries, after a song by Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel (2022), the drawing was part of a performance by Kolkata-born painter Nikhil Chopra and French artist Romain Loustau during the show’s opening, when viewers were presented with miniature chalk rocks on trays. Inspired by Goa’s coastal landscape, the piece foregrounded the ecological theme threaded throughout the show.

Photo documentation (top) and installation view (bottom) of NIKHIL CHOPRA and ROMAIN LOUSTAU’s The rock needs no water and the island never cries, after a song by Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, 2022, performance, canvas, charcoal, chalk, porcelain and a soundtrack, duration and dimensions variable, at "HAZE – Contemporary Art From South Asia," Fondazione Elpis, Milan, 2022. Photo by Noemi Ardesi. Courtesy the artists and Fondazione Elpis.

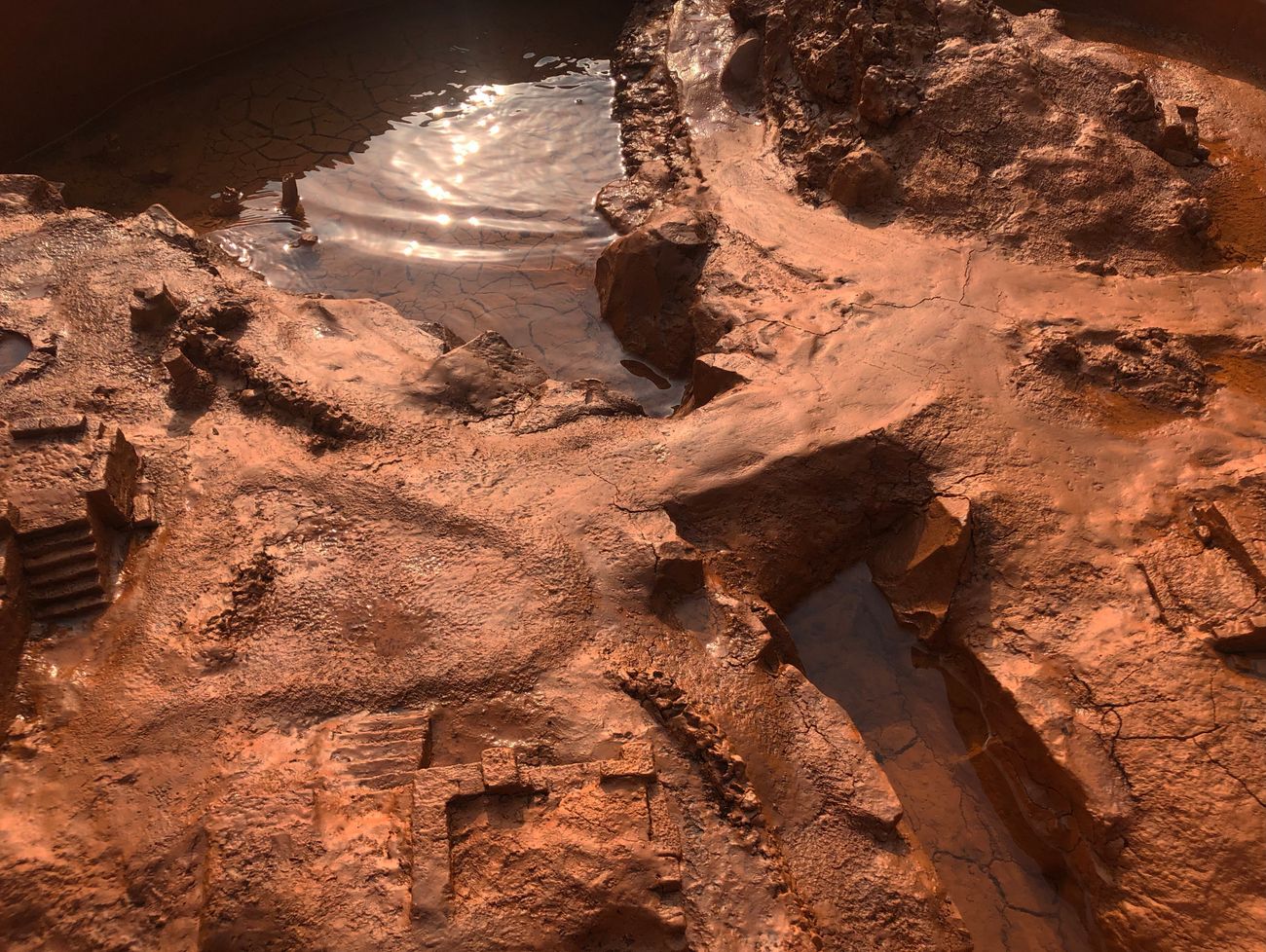

Adjacent was Sahil Naik’s kinetic installation All Is Water, And to Water We Must Return (2021), a 1.6-meter fiberglass miniature model of the ghost village of Kurdi in South Goa. Periodically pumped with water from below, the miniature becomes partially submerged in certain intervals; it reproduces the flooding of Kurdi since the Salaulim Dam was built in the 1980s. Submerged like many other villages in India, Kurdi resurfaces in the dry season when waters recede. Annually, the uprooted villagers gather to clean up the ruins. Warmer waters and heavy rainfalls are now leading to the ruins’ fast disintegration; eventually, Kurdi’s displaced communities would lose its physical remnants permanently.

On the gallery’s third floor, attention shifted to social and physical borders in conflict-ridden areas. Bani Abidi’s prints Security Barriers A-L (2008–19) comprises 26 digitally-reworked pictures of various security barriers placed at checkpoints in Karachi after the 9/11 attacks, with their exact location specified below the image. Rendered in vivid colors on a white background, the barriers appear emptied of their menacing connotation. Rather, they recall an abecedary of minimalist furnishings, and ironically comment on growing state securitization processes, now incorporated into urban design.

.jpeg)

Detail of SAHIL NAIK’s All Is Water, And To Water We Must Return, 2021, timed sculpture, fiberglass, paint, water, timer, motor, photography and eight watercolors on paper, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata / Mumbai.

Captivating ink and pencil drawings on topographic maps by Pala Pothupitiye occupied the opposite wall. Mannar Map, Pallampiddi Map, and Kokkilai (all 2017) address the postcolonial legacy of the artist’s native Sri Lanka, torn by a 30-year conflict between the Sinhalese majority and the Tamil minority. The latter’s presence increased significantly in the island during the British colonization as a labor force for plantations, exacerbating social tension. In the maps, coasts and bays morph into fantastic clawed creatures that recall the symbols of the Sinhalese’s and Tamil’s resistance—respectively a lion and a tiger—their prominent teeth and curly manes visualizing the fierce socio-ethnic struggle. A fourth map shows the Indian subcontinent turned upside down, a roaring beast atop of it, ironically overturning the balance of power.

The persistent legacy of the caste system in India informs Amol K. Patil’s series Stagnant; What is Human Becomes Animal?; Gaze Under your Skin (2017–22), featuring 11 differently sized ink drawings and a statuette of a cow. Deformed and twisted limbs are minutely rendered as disquieting creatures in black ink on cream and white paper. These appendages echo the rotting corpses of men and cows from the streets that the Dalits or “untouchables”—considered the lowest caste in the Indian social hierarchy—are expected clean up. Patil’s ongoing research addresses the presumed “destiny” of the Dalits, which bar them from social benefits such as education, condemning them to perpetual social exclusion.

.jpg)

Detail of AMOL K. PATIL’s Stagnant; What is Human Becomes Animal?; Gaze Under your Skin, 2017-22, ink on paper, dimensions variable.

A meditative exhibition, “HAZE” introduced Milanese audiences to a cross-section of stories about the problems that linger in the folds of modernization in the Indian subcontinent. Providing a concise but meaningful overview of the region’s artistic viewpoints, it is a promising start for a foundation that aims to bring new international perspectives to Italy.

“HAZE – Contemporary Art from South Asia” is on view at Fondazione Elpis, Milan, until March 5, 2023.

%20x%20135(H)%20px-03Rc-72dpi%20(2).jpg)