Reflections “On Foraging” at 421

By Nicole M. Nepomuceno

Installation view of "On Foraging," at 421, Abu Dhabi, 2022. All images courtesy 421.

The United Arab Emirates’ arid climate bolsters the impression that it is a barren landscape, yet there the lettuce thrives, soaking up its rich sunlight. To prevent their tips from wilting in the superabundant sun, farmer Abu Ahmed had the roof of his greenhouse painted with even stripes so that, as the sun moves throughout the day, the lettuce heads are only exposed to direct light half the time. As I learned about this from the accompanying publication of the exhibition “On Foraging: Food Knowledge and Environmental Imaginaries in the UAE’s Landscape,” it occurred to me that the history of humankind is simply a patchwork of instances where we made the most of our environments—hunting, cultivating, foraging—to survive.

“On Foraging” was an exhibition that explored this relationship between food, the people who cultivate it, and the terrain from which it is grown and harvested. Curated by Dima Srouji, Faysal Tabbarah, and Meitha Almazrooei, the show at 421 (formerly Warehouse 421) restaged the exhibition that was first presented at the UAE Pavilion at Expo Dubai 2020, with added works.

Installation view of "On Foraging," at 421, Abu Dhabi, 2022.

For this second iteration, 15 artists from the region presented inquiries and reflections on historical and present-day food production and their entanglements with class and culture. Of these projects, image-based works provided the most depth. Painted directly onto the wall, multimedia artist Moza Almatrooshi’s mural The Agriculture School: Sayed’s Mural (2022), depicting a small wooden house placed snugly within a lush landscape, opened the show by treading the idealization of the often-exploitative agricultural industry.

On the table across were printed photographs from Lithuanian photographer Auguste Nomeikaite’s 2021 series From the Field, capturing agricultural practices and technologies used in farms in the UAE. This echoed Awaiting Fruition (2021) by self-taught photographer Ammar Al Attar, which likewise looked at methods of cultivation. Documenting the growth of seasonal trees indigenous to the Gulf within domestic spaces, Awaiting Fruition recalls the relationship between produce and seasonality, as well as the homemade agricultural technologies that arise from growing food within the home. While their concepts are simple, both series provided necessary imagery of landscapes and technologies, grounding the exhibition into the physicality of its subject.

Installation view of TAREK AL-GHOUSSEIN’s Windows on Work, 2016, lamda print/diasec, 190 × 120 cm each, at "On Foraging," 421, Abu Dhabi.

Three works that focused on labor supplied the show’s substance. The late Kuwait-born Palestinian artist Tarek Al-Ghoussein’s photographic series Windows on Work (2016) occupied the entirety of a room with almost two-meter-wide prints featuring windshields of buses used to transport migrant workers. With the sunlight casting a brightness that starkly contrasts the dark interiors of the empty vehicle—the water bottles, pillows, and tissue boxes left unceremoniously by the bus window become still-life compositions. A genre that arose from the abundance of (exotic) produce drawn in by early market capitalism in Europe, the still-lifes in Al-Ghoussein’s series counter these lofty ideals associated with food via the scarce belongings of those who toil for them. Viewed from below, as one would a bus window while standing outside, the objects become larger-than-life, almost enshrined.

Honey, Rain and Dust (2016), Nujoom Al Ghanem’s documentary on bee-keeper Ghareeb and honey finders Aisha and Fatima, ruminates on our dependent relationships with nonhuman species who provide staple foods. Foraging for wild honey in the UAE’s northern mountains, Aisha and Fatima embody age-old eating traditions at a time where such practices are rendered peripheral to the consumption of mass-produced materials. Al Ghanem puts the viewer in close proximity to the bees, with close-up shots of the insects in their hives, flying around, and interacting with people. While it seems like a more environmentally considerate alternative, foraging is only sustainable if foragers respect the limits of the earth and its species. With alterations to the climate and landscapes hurting bee populations, the film provokes us to ask: how much of the bees’ honey can we—should we—still take?

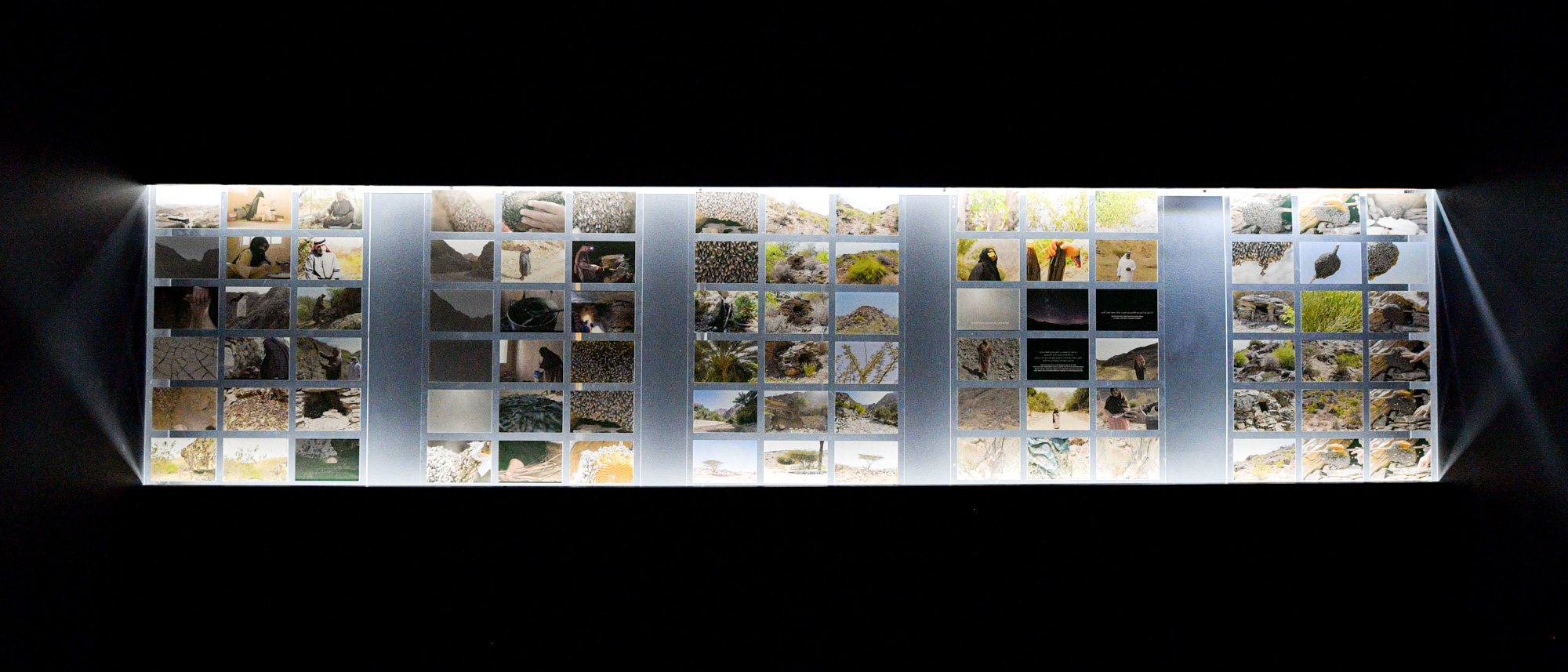

Installation view of NUJOOM AL GHANEM’s Honey, Rain and Dust, 2016, photo installation and film with sound and color: 86 min, at "On Foraging," 421, Abu Dhabi, 2022.

Commissioned by 421, Vikram Divecha’s 34-minute video Dohrana (2021) was an intimate watch as it follows the poet Shabbir wandering across gardens while a voice reads poems in Urdu. Meaning “to reiterate” in Urdu, Dohrana slowly pans across Shabbir’s body and the landscape he inhabits repeatedly before moving to the next destination. As the video progresses, Shabbir’s body becomes more and more intertwined with the foliage. The poems also shift their themes, from longing to hunger, migration to farmers’ rights. Continuing Divecha’s collaboration with municipal gardeners in Sharjah, these sumptuous gardens filmed in Dohrana are landscaping sites tended to by South Asian migrant workers in the UAE, where migrants account for about 90 percent of the population. This added layer brings to the fore the South Asian community’s expansive contribution to the country, including tending to the land itself.

“On Foraging” was a didactic show; tables filled with scientific reports on fruit farms, zines on bees, and various books encouraged visitors to be active foragers of information. At the same time, the show’s publication is one worth reading as a stand-alone repository of essays on food and the landscape. In walking through the exhibition, I found it timely to foreground our surroundings in a time of catastrophic changes in our climate, and ultimately, was in awe of how we have adapted and found nourishment from even the most formidable terrains.

“On Foraging” was on view at 421, Abu Dhabi, from October 9 to December 25, 2022.

Nicole M. Nepomuceno is ArtAsiaPacific’s assistant editor.