“Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, and Earth”

By Arthur Solway

Installation view of

Summer groups shows have long been gallery mainstays in which to pass the dog days of the season. At best they are curatorial test sites to highlight emerging talents, or platforms for imaginative theme-driven exhibitions. At their worst, they can sometimes seem like a summer picnic overrun by ants.

“Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, and Earth” at Pace Palo Alto took the thematic approach by bringing together the work of five prominent women artists from China. Curated by Michael Xufu Huang, patron and founder of Beijing’s X Museum, the exhibition featured paintings, works on paper, and sculpture by Cui Jie, Yang Bodu, Li Shurui, Zhang Zipiao, and Zhang Ruyi, each representing one of the five unifying elements in ancient Chinese philosophy.

Denoting the element of metal, Cui Jie’s solitary painting in this exhibition, Swan Swirl Chair #2 (2020), is a nod to Danish architect Arne Jacobsen, who designed this chair in the late 1950s. Much of Cui’s work alludes to the history of modernism with a disquieting flair for the dystopian when it comes to architecture and cityscapes. A black and pink squeegeed background with intensely incised areas elevate the work’s physicality, transforming this iconic mid-century piece of furniture into an abstract sculptural monument. A few minor color pencil sketches of other chair motifs were included; however, it would have served the exhibition well if more of Cui’s paintings had been presented.

CUI JIE, Swan Swirl Chair #2, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 150 × 120 cm. Courtesy Pilar Corrias, London; and Pace Gallery, London / Palo Alto / Seoul / Hong Kong / Geneva / New York / East Hampton / Palm Beach.

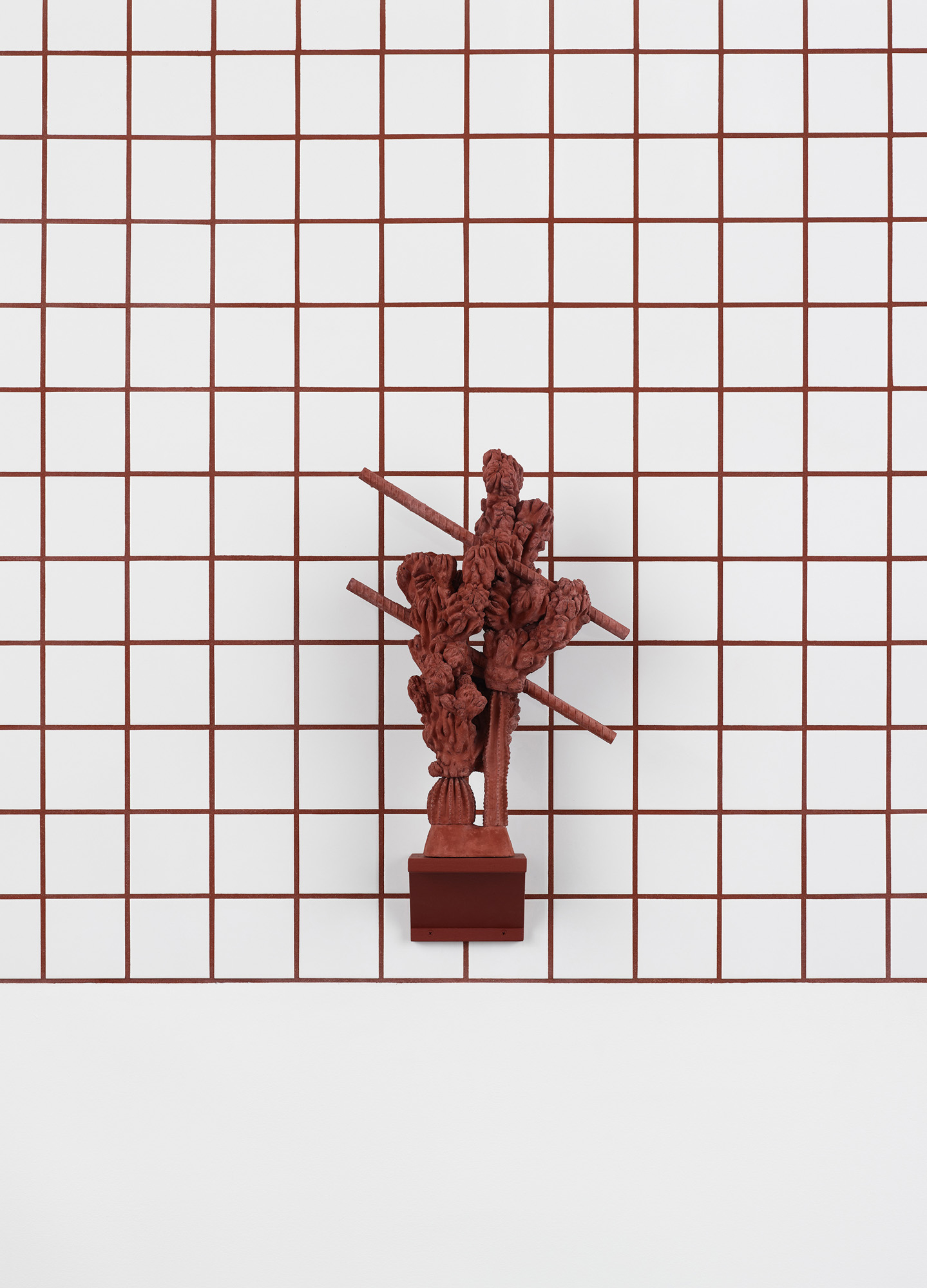

It became a stretch to connect the curatorial premise of this show, although Zhang Ruyi’s familiar sculptures of cast concrete cacti seemed easy enough to equate to earth. At the gallery’s entrance, along with Cui’s single painting, two pristine white tile shelves for Zhang’s hybrid cacti forms feel like relics of a bygone world. A somewhat more ambitious installation using printed vinyl rather than actual ceramic tile had its own cloistered area in a partitioned section of the gallery. There, a pair of wall-mounted, rust-colored sculptures, Grafting 1 (2018) and Puncture (2019), were presented. Zhang’s choices of palette for her pigmented botanical specimens—concrete gray, red, blue or teal—combined with the clinical white tile seem to amplify their feeling of detachment from the natural world as we know it.

ZHANG RUYI, Grafting 1, 2019, concrete, pigment, flower pot, steel, 66 × 25.6 × 16.5 cm. Courtesy Don Gallery, Shanghai; and Pace Gallery, London / Palo Alto / Seoul / Hong Kong / Geneva / New York / East Hampton / Palm Beach.

ZHANG RUYI, Puncture, 2018, concrete, pigment, steel, 64.9 × 37 × 20.5 cm. Courtesy Don Gallery, Shanghai; and Pace Gallery, London / Palo Alto / Seoul / Hong Kong / Geneva / New York / East Hampton / Palm Beach.

Representing water, Li Shurui’s pair of plum flower paintings, Making Up for Lost Spring No. 49 and Making Up for Lost Spring No 50 (both 2021) were conceived during the earlier days of the pandemic. Symbolic of spring’s plum season rains in China, they are meticulously airbrushed, in soft, luminous hues of pale green and lavender. Each central blossom-shaped canvas is surrounded by a group of scattered teardrop petals. These are a decorative shift for the artist who is well known for her more minimalist abstract works.

Installation view of LI SHURUI

Most of the artists in this exhibition are in their thirties, with the exception of Li, who was born in 1981, and the youngest of the group, Zhang Zipiao, born in 1993. Four of the latter’s paintings dominated the main space, the largest of which, Peony 08 (2021), measures 230 x 190 centimeters. Zhang also riffs on images of flowers to represent her element, fire. They are visceral, fiercely gestural abstract works; their physicality is admirable even if they feel like throwbacks to Abstract Expressionism.

The only figurative works in this exhibition were by Bodu Yang, a realist painter who takes her inspiration from intimate experiences of viewing art in museums or galleries. In the Museum 2021 May (2021), the larger of two works in the show, is rendered in plush, earthy tones, and offers a sense of nuance and attention to detail. A tiny wooden figure, elevated to eye level, strikes a pose as if dancing before a window to the outside world.

While this showcase of Chinese women artists was indeed refreshing and overdue, there were missed opportunities by the curator to better bolster his elemental premise. Hu Xiaoyuan came to mind immediately for her meticulous, lifelike, and labor-intensive tracings of wood grain on silk. Or Shanghai-based Shi Zhiying, well known for her mesmerizing monochromatic paintings of seascapes, would have been an excellent choice for the subject of water. While perhaps too pedantic or obvious, more literal representations of the five elements would have strengthened the curator’s thesis.

Arthur Solway is a contributing editor at ArtAsiaPacific.

“Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, and Earth” was on view at Pace Gallery, Palo Alto, from July 14 to August 21, 2021.

%20x%20135(H)%20px-03Rc-72dpi%20(2).jpg)