Elusive Edge: Philippine Abstract Forms

By Sean Carballo

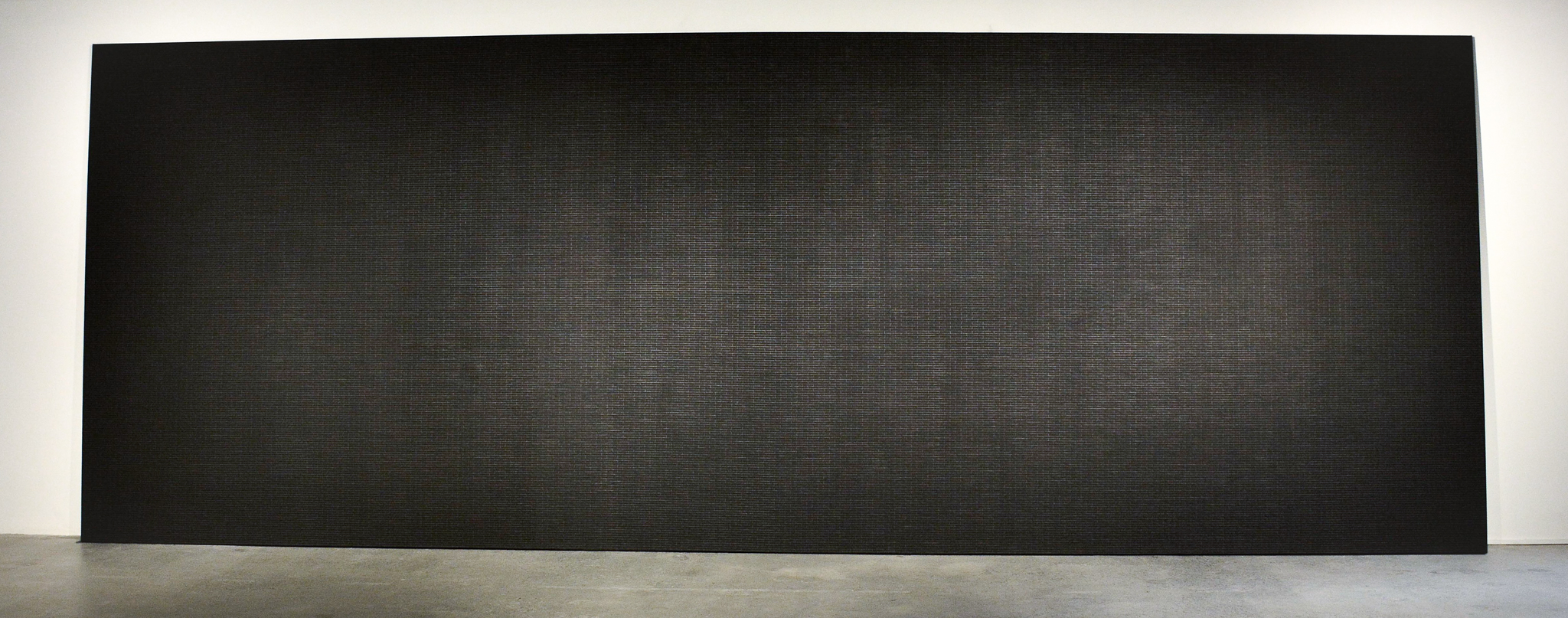

MARIA TANIGUCHI, Untitled, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 289.6 cm x 792.4 cm, "Elusive Edge" at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila. Silverlens Galleries Collection. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

Elusive Edge: Philippine Abstract Forms

Metropolitan Museum of Manila

Jun 13–Aug 31, 2023

What purpose does lineage serve with regard to understanding abstract art?

One might reasonably argue that any artistic lineage is fraught, given how it

institutes a trajectory that often parcels complex, thorny movements and

counter-movements into tidy, simplistic compartments. Others might argue that

abstract art struggles against such direct historical framing. To abstract,

after all, is to excise. It is the work of distillation, the process of

extracting the material of lived experience until what endures is a flash of

feeling, an energy beyond imagery.

Taken on these terms, it is no surprise that some consider abstract art as

an evasive, slippery art, prone to antagonisms across cultures and political

orientations. “Abstract art is attacked as the enemy with such a passionate

urgency,” art historian Alice Guillermo wrote in a 1983 essay, alluding to

accusations of escapism and conservatism allegedly inherent to the practice. To

couple lineage and abstraction, then, at least on the surface, seems like a

thankless task.

“Elusive Edge: Philippine Abstract Forms,” curated by critic and professor

Patrick D. Flores, alerted audiences to abstract art’s traits but only as a

foundation for scrutinizing what exactly constitutes this broad concept.

Displaying a loose genealogy of works from the 1960s to the present day, the

exhibition served as an appraisal of abstract art in the Philippines, bringing

into focus its manifold configurations—from Arturo Luz’s relief carvings on

plywood and Ramon Orlina’s glass sculptures to Gary-Ross Pastrana’s sharply

defined collages and Maria Taniguchi’s brick wall installation—as a tactic for

encountering a new abstraction’s historical, though assuredly not linear,

trajectories.

The sweeping scope on display suggested that Filipino artists, deploying

abstraction to sift through their own artistic preoccupations, have always been

attentive to the effort of mediation, or, as Flores put it, “how the

Philippine artistic ecology and intelligence decisively responded to the

abstract aesthetic, conversing in both its international and vernacular

registers.” Lineage, as the show understood it, does not tread a straight line

but teeters, falls back on itself, reorganizes, and shuffles back to its feet

again.

,%20Metro%20Series%20(Tunnel).jpg)

GARY-ROSS PASTRANA, Untitled (Flight), 2021, collage and acrylic on canvas, 61 cm x 46 cm, and Metro Series (Tunnel), 61 cm x 48 cm, "Elusive Edge" at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila. Silverlens Galleries Collection. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Manila.

Flores’s attitude to curation in “Elusive Edge” was speculative rather than

prescriptive. And despite the exhibition’s formidable framework, encompassing 85

works organized into five clusters, Flores offset this intricacy by

undergirding the show with questions that catalyzed his thinking. Why is

abstract art so often pitted against figurative art? How have artists unsettled

such rigidities? Can abstract art acquire an ethical position? What does a

Filipino expression of abstraction look like? These inquiries, sparked by

Flores’s probing intellect, became the generative ground for the

exhibition.

Such extensive inquiry gave the works a chance to converse with one another

in unexpected ways. There was a fidgety spirit animating the show,

providing thrust and physicality as we were shuttled through one piece after

another. The show asked—no, demanded—that we confront color as a snarl of energy,

transfiguring and shapeshifting into forms bounded and unbounded. Jess Ayco’s

sensually apocalyptic reds in Untitled (1970) came into fierce contact

with the much more geometric and stable variations in Lamberto Hechanova’s Homage

to Julie (1968). Likewise, repetitions of black emerged as either

unsettlingly pensive, as in Nice Buenaventura’s charcoal triptych Ditto

Studies 1–3 (2017), or tranquil to the point of hypnosis, as in Maria Taniguchi’s

brick painting Untitled (2018).

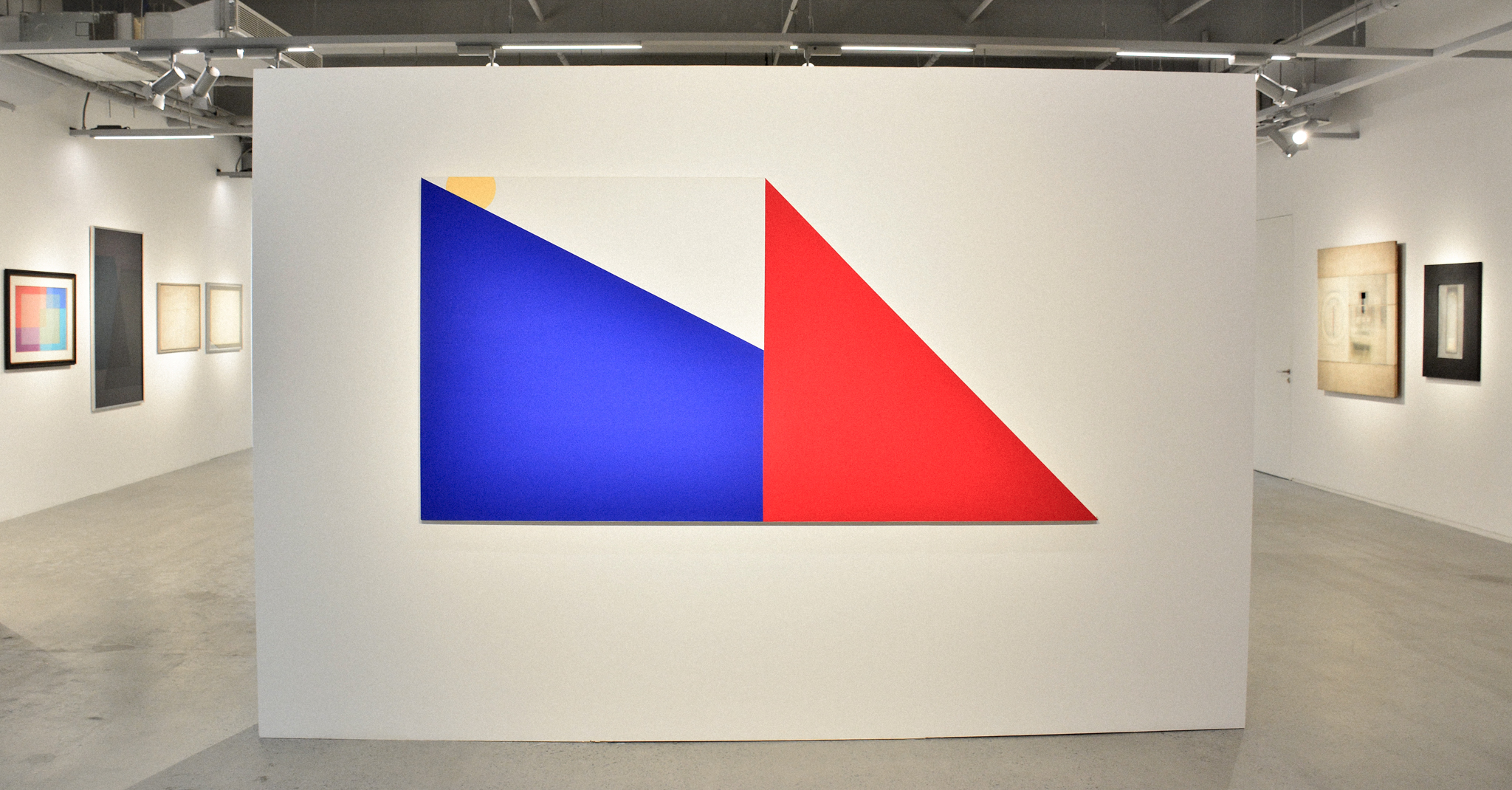

In one section of the show, which tracked the development of hard edge and

color field approaches, jolts of color were sublimated into monochromatic,

razor-like forms, such as in Leo Valledor’s A.I.R. (Artist in Residence) (1981).

Altering the Philippine flag’s shape until it is transformed into a sharpened

structure, making no distinguishable hierarchy between the blues and reds

(symbols for peace and war respectively), Valledor, a Filipino born in San

Francisco, grafts questions of national history and diaspora onto the very

activity of abstraction. A mediator himself, Flores showcased throughout

“Elusive Edge” the instances in which practitioners of the abstract form have either clung to tradition or chosen to deviate from it. Conveying this dynamic of hold

and release, the exhibition was an encompassing and purposeful feat, a

remarkable proposition of abstraction and its decisive fusions.

LEO VALLEDOR, A.I.R. (Artist in Residence), 1981, acrylic on canvas, 122 cm x 244 cm, at "Elusive Edge" at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila. Lina Juntilla Collection. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Manila.