Beneath the Surface: Wu Chi-Tsung

By Judy Chiu

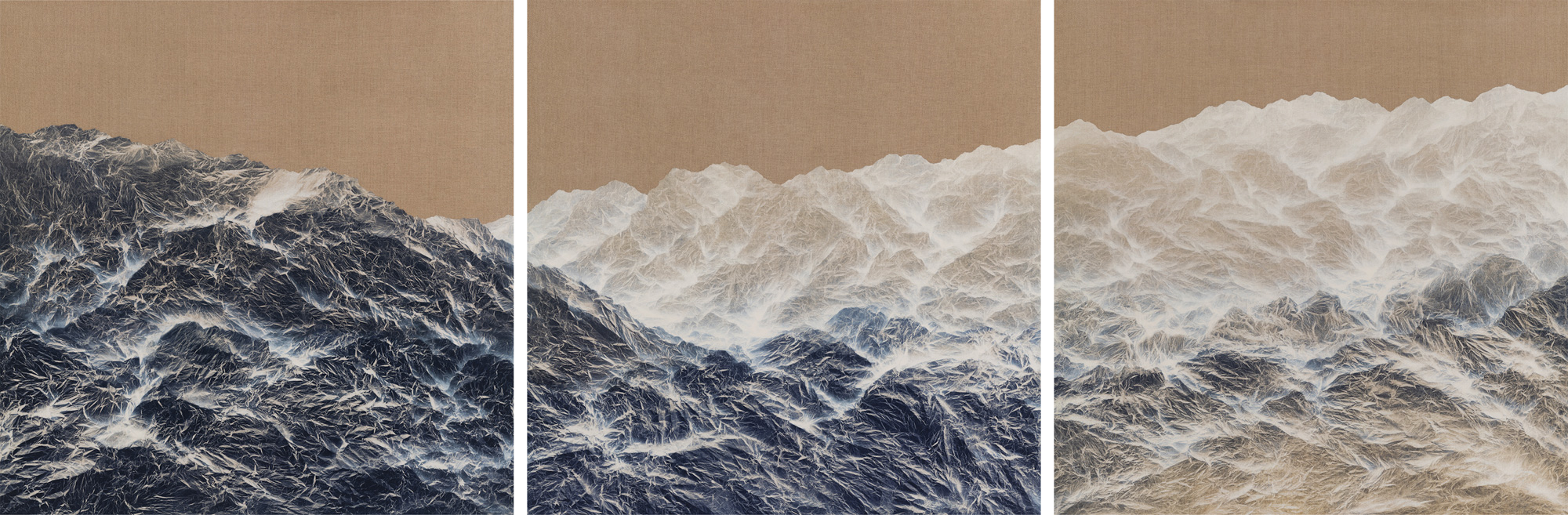

WU CHI-TSUNG, Cyano-Collage 095, 2021, cyanotype, Xuan paper, acrylic gel, acrylic, 200 × 600 cm. All images courtesy the artist and Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong.

At the entrance of Wu Chi-Tsung’s exhibition “Exposé” (2021), curated by Ying Kwok at Galerie du Monde, stood a six-part folding screen depicting blue mountain peaks. The work was made from cyanotype-treated Xuan paper (Chinese rice paper), a laborious process derived from early photography whereby Wu translates the markings of light and time into shades of blue.

The folding screen ushered visitors into the main exhibition space, where the eye-catching, three-part Cyano-Collage 095 (2021) evoked a great mountain range across an entire wall. Its wrinkled texture mimics the contours of majestic slopes and valleys, while the contrast between its deep indigo shades and its misty white layers recall the subtle ink-control seen in Chinese shanshui painting. Wu is heavily inspired by traditional Chinese landscapes, although he eschews the traditional medium of ink in favor of cyanotype. Trained from a young age in Chinese calligraphy, ink painting, and watercolor, Wu turned to cyanotype as a way to simultaneously pay homage to and reinvigorate classical ink aesthetics.

Installation view of WU CHI-TSUNG’s Cyano-Collage 094, 2021, cyanotype, Xuan paper, acrylic gel, acrylic, 225 × 540 cm, at "Expose," Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong, 2021.

Wu started experimenting with cyanotype in his Wrinkled Texture (2012– ) series as a means of reinterpreting the cun fa (texturing method) of Chinese landscape painting. Wu’s creative process is a strenuous one. To start, he soaks Xuan paper in a photosensitive solution. Then, he crumples the paper and exposes it in the sun for 30 minutes. Strong sunlight results in dark indigo hues, while cloudier days bring lighter blues. The paper is subsequently washed and flattened in a water tank for an hour to set the final image; it is during this step that Wu first sees his work. After selecting a section he finds interesting, he crops and mounts it on a canvas or scroll. “My creative practice is filled with endless experimentations. Every step along the process, I am constantly exploring the possibilities within, and always failing too,” Wu said in an interview with Obscura magazine. Even with limited control over the final image, Wu still manages to capture the essence of shanshui painting through his strategic cropping and framing of the work. In Wrinkled Texture 107 (2021), for instance, the placement of darker blues at the bottom of the frame grounds the image against its overexposed counterparts, and creates an illusion suggestive of shanshui’s classic peaks.

In his Cyano-Collage (2015– ) series, Wu harnesses the uncontrollable aspects of this process—the weather, light intensity, wrinkle patterns—by collaging multiple sheets of paper on a canvas and sealing them with several layers of matte acrylic gel. In Cyano-Collage 086 (2020), for example, he adds layers of white rice paper on top of dark blue pieces to create an illusion of mist wavering between valleys. Paper fibers can even be seen in some white layers, highlighting its soft, nebulous quality. Such fine details achieved through his delicate craftsmanship create an impressive dimensionality. Meanwhile, Cyano-Collage 096 (2021) overlays treated Xuan paper in a blue gradient onto an unexposed paper background, a nod to the traditional Chinese painting technique liu bai (leaving areas blank) that creates breathing room.

WU CHI-TSUNG, Cyano-Collage 086, 2020, cyanotype, Xuan paper, acrylic gel, acrylic, 70 × 190 cm.

“Exposé” demonstrated Wu’s ability to reconcile seemingly contradictory qualities. The depth and elevation created by the textures in his works belie the flatness and smoothness of their surface. The illusions of ink mountains are reconsidered on closer inspection. What was unintentional—colors and patterns dependent on natural forces—transforms into intention through Wu’s meticulous arrangements. Wu’s inventive practice reinterprets the traditions of Chinese art, and invokes hidden depths beneath the works’ surface.

Judy Chiu is an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.

Wu Chi-Tsung’s “Exposé” was on view at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong, from March 24 to June 13, 2021.