The Essential Works of Lee Mingwei

By Camilla Alvarez-Chow

LEE MINGWEI, Guernica in Sand, 2006- , mixed-media interactive installation with sand, wooden island, lighting, 1300 × 643 cm. Courtesy Taipei Fine Arts Museum.

*updated on March 5, 2024.

Whether an intimate dinner, a private concert, or an encounter with objects from the past, Lee Mingwei stages participatory events that take people out of the everyday through unique and contemplative experiences. Beginning in the late 1990s, these encounters were often created by the artist himself. In recent years, Lee has increasingly incorporated performers as collaborators and actors. Throughout the artist’s practice, he has reinterpretated and restaged rituals from daily life in the spaces of museums, galleries, and other cultural venues.

Today based between New York, Paris, and Taipei, Lee was born in Taichung in 1964. As an adolescent, beginning at the age of six, he spent six summers training under the tutelage of a Ch’an Buddhist monk, learning the tenets of the sixth-century, indigenous Chinese belief system. The religion’s core beliefs revolve around the experiential and relational, where the source of spiritual wisdom lies in the mundane instead of celestial realms; the state of enlightenment is not something to be sought out but already exists within ourselves and can be practiced in our everyday lives. From these early studies, Lee learned about the important interrelations between people and how the ordinary can be transformed through acts of compassion.

In the 1990s, after Lee moved to the United States, he obtained a bachelor of fine arts from California College of the Arts in San Francisco in 1993, during which time he studied with the artist Suzanne Lacy, who introduced “new genre public art” that was often political and made outside formal institutions, situations which brought the artist into direct engagement with the audience. Lee went to earn an MFA in sculpture from Yale University in 1997. His artistic career became an amalgamation of Buddhist philosophy and late 20th-century socially engaged art where his participatory installations have gained international renown. He exhibited at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York in 1998 and then in the Taiwan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2003. In 1999, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston invited him as an artist-in-residence. The following year, in 2000, he staged the exhibition “Living Room,” which he later adapted into a more permanent space in 2012, in the museum’s new wing.

Lee’s recent exhibitions include “Li, Gifts and Rituals” (2020) at Gropius Bau in Berlin and the creation of the permanent installation Spirit House (2022– ) at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, and “The Gifts of Connection” in 2023 at the Kimball Art Center, Park City, Utah. His solo exhibition “Rituals of Care” opened on February 17 at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco – de Young Museum. Later in the year, starting from August 27, he will stage his performative installation Sonic Blossom (2013– ) at M+ in Hong Kong for one month.

Ahead of these major projects in 2024, here is a look at eight influential artworks by Lee Mingwei.

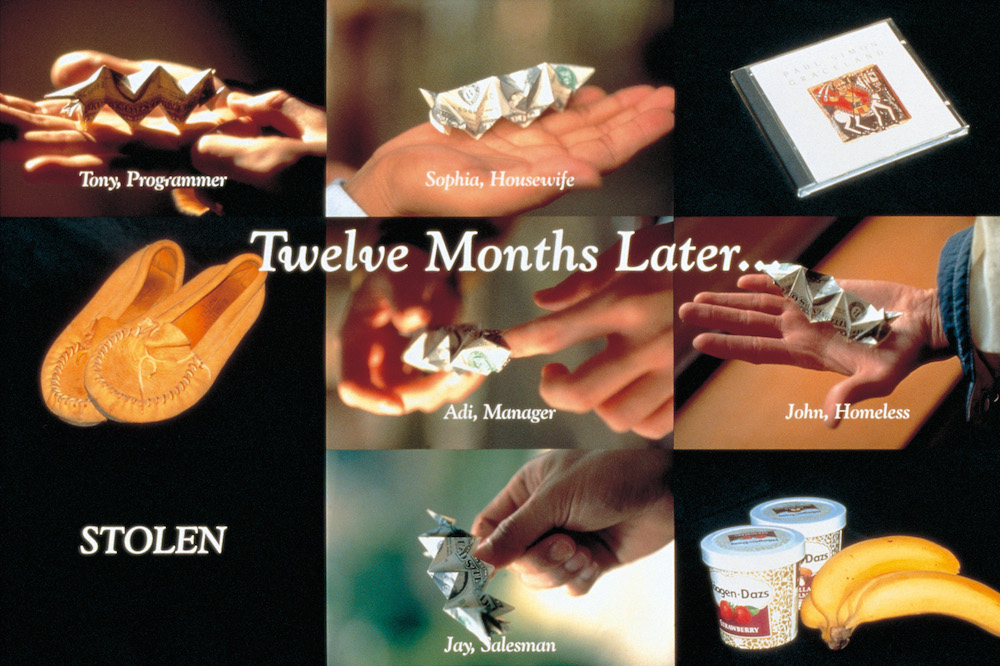

LEE MINGWEI, Money for Art, 1994/97, silver-dye bleach prints, 27.9 × 35.6 cm each. Courtesy the artist.

Money for Art (1994/97)

One fateful day in 1994, Lee Mingwei sat at a cafe and started to fold nine US ten-dollar bills into small, zigzagging origami. He garnered attention from passersby and offered the finished pieces to them in exchange for their phone numbers, to receive updates on the sculptures every six months. As half a year went by, Lee took photographs that documented what had become of the mini sculptures. Some were used to buy footwear, a CD, and groceries, while one of the participants, a student, had their sculpture unfortunately stolen. Despite these rather mundane outcomes, the project led to a curious event. A Vietnam veteran named John, who was unhoused at the time, took part in Lee’s social experiment. As the months passed he proudly showed the artist the sculpture intact each time they met. To John, the small artwork that fit in the palm of his hand held more value than any short-term comfort he could have obtained from spending it.

Lee later updated Money for Art for an exhibition in 1997 that featured a simple open shelf filled with geometrical, origami-folded USD 1 bills. Visitors could exchange them for another item they thought correlated with its value, leaving behind their name and profession stated on a card. Lee’s artwork became an open invitation for participants to reflect on the same question that fuelled the creation of his work: “When, under what circumstance, does one [the art] equal the other [money]?”

LEE MINGWEI’s The Dining Project, 1997- , mixed-media interactive installation with wooden platform, tatami mats, video, at "Lee Mingwei: Li, Gifts and Rituals," Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2020. Photo by Laura Fiorio. Courtesy Gropius Bau.

The Dining Project (1997– )

During a period of loneliness while pursuing his graduate degree at Yale University, Lee put up posters all over campus extending an invitation to anyone who would be interested in “sharing foods [sic] and introspective conversation.” This became The Dining Project (1997– ), for which the artist prepared a meal in accordance with the dietary preferences of his guest. In later versions, participants were chosen to have a private after-hours dinner with Lee at venues such as the Whitney Museum of American Art or New York’s Lombard Freid Fine Arts. For the exhibition, one of these dinners was recorded—the guest was kept anonymous by having the camera’s focal point on the food and sound was altered to become barely audible. With this example, and their imagination, Lee invited audiences to witness these experiences as examples of where the little things in life that are taken for granted become powerful artistic engagements when elements of generosity are introduced.

Installation view of LEE MINGWEI’s The Letter Writing Project, 1998- , mixed-media interactive installation, wooden booth, writing paper, envelopes, 3 pieces, 290 × 170 × 231 cm each, at Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. Photo by Yoshitsugu Fuminari. Courtesy Mori Art Museum.

The Letter Writing Project (1998– )

When Lee’s maternal grandmother passed away, he dedicated a year-and-a-half to penning his belated reflections to her. Pouring onto paper the thoughts and feelings that he was not able to express before her death, Lee developed the idea for The Letter Writing Project (1998– ). When the work was first shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and later at The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, Lee included three booths constructed out of wood and translucent glass. Inside of these structures, Lee invited visitors to either stand, sit, or kneel at a small table and write about things that should have been said but never were—such as unexpressed gratitude, forgiveness, or an apology to loved ones who were no longer there. After finishing their letters, participants place them in envelopes either sealed for the museum to send it by post or unsealed in a slot on the booth’s wall for others to read. At the end of the exhibition, the curator of the exhibit collected letters that are for the deceased and sent them to Lee, who then performs a ritual to “purify them in flames.” The Letter Writing Project creates a contemplative space that offers the participants both solace and catharsis.

Installation view of LEE MINGWEI’s The Sleeping Project, 2000- , at Lombard Freid Gallery, New York. Courtesy Lombard Freid Gallery.

The Sleeping Project (2000– )

The Sleeping Project (2000– ) was sparked from another memory from the artist’s life. When Lee was a high-school student, he was traveling overnight on a train from Paris to Prague. En route, he met an elderly Polish gentleman, the sole survivor in his family of a Nazi concentration camp, who shared stories about his life during the German invasion. Lee carried this experience with him for years, and it inspired The Sleeping Project (2000– ), for which he staged an intimate situation with randomly selected participants. Two beds and bedside tables were located in the exhibition space where the artist and a participant would sleep overnight. Each participant brought an object they regularly kept on their bedside with them. During the evening, Lee and the stranger would share a moment of platonic intimacy. These conversations were recorded and played the next morning along with a display of the item left by the participant, as testaments to what occurred the previous night.

Installation view of LEE MINGWEI’s, Guernica in Sand, 2006- , mixed-media interactive installation with sand, wooden island, lighting, 1300 × 643 cm, at "Lee Mingwei: Li, Gifts and Rituals," Gropius Bau, Berlin, 2020. Photo by Laura Fiorio. Courtesy Gropius Bau.

Guernica in Sand (2006– )

Lee’s installation Guernica in Sand (2006– ) is a replica of cubist painter Pablo Picasso’s famous antiwar composition Guernica (1937) made entirely of colored sand on the floor in a 23-by-11 meter design. While the original painting commented on the devastating consequences of war—specifically, the Spanish Fascist bombing of a Basque town during the civil war—Lee transforms this iconic painting to explore “impermanence as a lens for focusing on such violent events in terms of the ongoing phenomena of destruction and creation.” (Opposites, in this case, destruction and creation, are reliant on each other to achieve harmony in Buddhist ideology.) The majority of Guernica in Sand is formed prior to the exhibition opening, and Lee reserves one day’s work to be completed in the middle of the exhibition period. After that, during a separate day, from noon until sunset, he allows visitors (one at a time) to walk barefoot through the sand-painting, destroying it. The final stage involves four participants sweeping the sand toward the center of the installation where it is left until the exhibition’s conclusion. The sand is then recycled back into nature to complete the cyclical process. The work is never in one state of existence, reflecting the continual change in life.

Lee Mingwei, "The Mending Project," 2009

The Mending Project (2009– )

The Mending Project (2009– ) exemplifies Lee’s innovative style of staging an experience with the audience through one-on-one interactions. In this project, a gallery docent or the artist himself sits at a table and waits for visitors to bring clothes that need repair. The visitor sits at the other side of the table, perhaps engaging in a conversation, and using thread and needle, the artist or surrogate patches up the garment with colorful thread from spools attached to the wall. Maybe the object’s owner will share memories about the piece of clothing: its history, the places it has been to, or the experiences it has lived through. After the clothing is fixed, the garments remain for the duration of the exhibition still attached to the spools of thread hung on the wall. The process leads to a shared awareness of how interconnected our lives are with those of others and how these threads are created and repaired through time. As Lee revealed in an interview with ArtAsiaPacific, the conceptual installation was inspired by the traumatic event of 9/11 and is a work about “how humans can move forward with integrity, trust, and intimacy.”

LEE MINGWEI, Sonic Blossom, 2013- , participatory performance installation with chair, music stand, costume (designed by Lee Mingwei in collaboration with Akira Isogawa or Kelima K) and spontaneous song. Photo by Randy Dodson. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Sonic Blossom (2013– )

First staged at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, in Seoul, Sonic Blossom (2013– ) is a participatory performance installation with a simple, elegant premise. The work involves a skilled opera singer walking through the gallery halls and approaching a visitor with the question, “May I give you a gift?” If the visitor accepts, the performer leads them to a chair where they experience a gift of a song: one of five Lieder by Franz Schubert. Adorned in a patterned draped robe that the artist calls the “Transformation Cloak,” the performers stage this private recital in front of other museum guests. The idea for Sonic Blossom came from Lee’s memories of spending time with his mother while she was bedridden in the aftermath of surgery, and they both took great comfort from listening to Schubert’s music. Seeing his mother’s frailness brought the acknowledgment of Lee’s own mortality and it occurred to him that our brief lives are made even more precious, even more beautiful, in their brevity. This impactful performance frequently induces tears in the recipient, as well as the singer, demonstrating the power of generosity.

Installation view of LEE MINGWEI’s Spirit House, 2022, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Sydney, 2022. Photo by Diana Panuccio. Courtesy AGNSW.

Spirit House (2022)

Lee’s most recent project, Spirit House (2022), was commissioned by the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) for its new architectural addition known as Sydney Modern. This work was inspired by Lee’s first visit to the AGNSW in 1999 where he came before a standing Buddha marble statue from the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE). The encounter, Lee has explained, led to him opening himself spiritually and inviting the spirit of the enlightened being to accompany him on his own emotional journey, with the promise of returning the spirit back home when the journey reached its conclusion. More than 20 years later, Lee designed a dome-shaped interior space made of rammed earth that houses a bronze Buddha sitting in meditation. Visitors are welcome to take the stone wrapped in rattan as a spiritual guide for their own personal journey with the knowledge that when it is finally fulfilled, they will come back and return the stone for someone else to take. If there happens to be no stone in the Buddha’s hands when one visits, visitors can ask for the spirit as an unwavering guide. Inspired by personal memories, Lee’s work in turn aspires to spiritually ignite the audience’s everyday rituals.

Camilla Alvarez-Chow is an editorial assistant at ArtAsiaPacific.

“Rituals of Care” is view from February 17 to July 7, 2024, at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco – de Young Museum.