Direct Action: An Interview with Ge Yulu

By Anqi Li

Portrait of GE YULU. Photo by Li Yingwu. All images courtesy the artist and Beijing Commune, unless otherwise stated.

Ge Yulu has been surprising the art world in China since 2017. As a student, he utilized the literal translation of “lu” as “road” in Chinese and installed a road sign carrying his name on an anonymous Beijing street; in Eye Contact (2016), he gawked at a surveillance camera; and volunteered to do the work of three museum workers so they could take time off in Holiday Times (2020). Where did he get these unusual ideas? What does he really care about as an artist? In this first English interview with Ge, he opens up to share behind-the-scenes stories of his social-intervention projects, resistance, and struggles with reality.

Photo documentation of GE YULU’s Ge Yulu, 2013-17, public performance in Beijing.

Photo documentation of GE YULU’s Ge Yulu, 2013-17, public performance in Beijing.

Your single-channel video Eye Contact comprises two-hour-long footage of you staring into a public security camera until the person sitting behind the monitor came out to stop you. What motivated you to do this and did you get into any trouble?

During that time, I was working in Xu Bing’s studio on his film Dragonfly Eyes (2017), which required editing thousands of hours of surveillance footage. I then realized that our existing discourse on surveillance cannot yet epitomize my experiences with it. At the same time, I have been interested in ways to surface human beings from enormous systems. I realized that it is people who sit inside these control rooms, appointed to monitor us, not the conceptual idea of the “Big Brother.” My work in Xu’s studio made me one of these people behind the security camera, neglected by both the people I was observing and the discourse on surveillance.

Outside the studio, I felt passive being observed through these lenses, but with Eye Contact, I found ways to depart from this system. When I look into the security camera, my eyes meet those of the person behind it. I believe this system cannot simply shield this gaze, which is not just eye contact but a mirror image and a reflection. Since then, whenever I see a security camera, I no longer take it as a symbol to turn against. It is more like looking at a friend, and this suffocating system can be totally ignored for that brief moment.

This project is not just intended to criticize surveillance, because I want there to still be space for open discussions. The space between criticism and praise, approval and denial, is dynamic, so it’s not surprising that I stir trouble and disagreements from time to time. I don’t really worry about causing trouble, it helps me understand reality better.

Photo documentation of GE YULU’s Eye Contact, 2016, single-channel video: 2 hr 14 min 52 sec.

Photo documentation of GE YULU’s Eye Contact, 2016, single-channel video: 2 hr 14 min 52 sec.

You once told me that you were very empowered by how artist Hasan M. Elahi responded to a mistaken FBI investigation by initiating a “self-surveillance” project where he shared his everyday activities in detail, not only with the FBI, but with the public online. He described his approach as “creative problem-solving.” I see a similar method in your Untitled (2019) portrait series, a product of self-censorship. What encouraged this work?

I originally planned to show digital prints of me wearing a suit for the Prix Yishu 8 exhibition in Beijing (2019), but when they were up on the walls, the organizer told me they felt very uncomfortable seeing these images, and stressed that they may have a bad impact for other visitors. This obviously didn’t make any sense and I was furious. Are ordinary people taking professional portraits considered a risky thing now as well? I decided to ruin this work by covering my face with spray-painted color blocks. Ironically, the organizer then green-lighted my “ruined” portraits. These now-abstract images visually departed from my original plans, but passed through the exhibition organizer’s self-censorship. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry, but responding to the reality of censorship by abstracting this work might have called more attention to it.

Do you have other experiences of being censored?

There are too many of them. I have had all kinds of experiences that invoke humiliation, anger, and frustration. ■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■—■■■■■ ■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■■■—■■■ ■■■■ ■■ ■■■ ■■■■, ■■■■■ ■■ ■■ ■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■. ■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■■■■, ■■■■■■■ ■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■■■■, ■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■’■ ■■■■ ■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■-■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■-■■■■■■, ■■■■■■■ ■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■ ■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■. ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■, ■■■■■ ■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■ ■■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■, ■■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■ ■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■. ■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■ ■■ ■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■■ ■■■■■■■■■■.*

You can only learn to adapt to this environment and take a broad view of censorship’s multifaceted nature. For example, I would sometimes convince myself that lacking an exhibition budget or clashing ideas with peer artists can be censorship as well. They are all factors that limit your art-making, with ideology and politics being some of them. Complaining makes no difference and it is a daydream to try to correct this system. I would rather rely on what I can do in my practice, and not expect changes initiated by others.

* This text is blocked out by the artist after his self-censorship.

Installation view of GE YULU’s Untitled, 2019, a set of 18 digital prints on canvas, spray paint, and wooden frame, 86 × 60 cm each, before censorship.

Installation view of GE YULU’s Untitled, 2019, a set of 18 digital prints on canvas, spray paint, and wooden frame, 86 × 60 cm each, after censorship.

You have mentioned your admiration of anthropologist and anarchist activist David Graeber’s concept of “direct action.” Do you apply this to your practice?

Yes, I like some of Graeber’s concepts. Direct action is to dig your own well when you don’t have water, instead of protesting in front of the government and questioning why there is no water provided. The latter is about confrontation, which can easily result in individual destruction, and by nature, its dependence is on the government. On the contrary, the former not only solves the most urgent need but also denies the necessity of a central rule. I think anarchism is not about eliminating the government, but about living your life the same way with or without it. This can be an inspiration for other fields, such as the art industry, in relation to exhibition spaces and artworks.

I see the work of a social activist in your practice and this makes me think of many artists who also engage with sociopolitical issues in Hong Kong, particularly during and after the 2019 anti-extradition bill movement. After the national security law was enacted, many artworks started to fall into obscurity. Is there anything you would like to share with your fellow artists in Hong Kong?

I can totally empathize with these feelings. It can be very defeating to face such a force majeure, but as long as there is breath left, there will be ways out. I want to recommend the movie Hibiscus Town (1986) directed by Xie Jin. It gave me lots of hope and power when I was in despair.

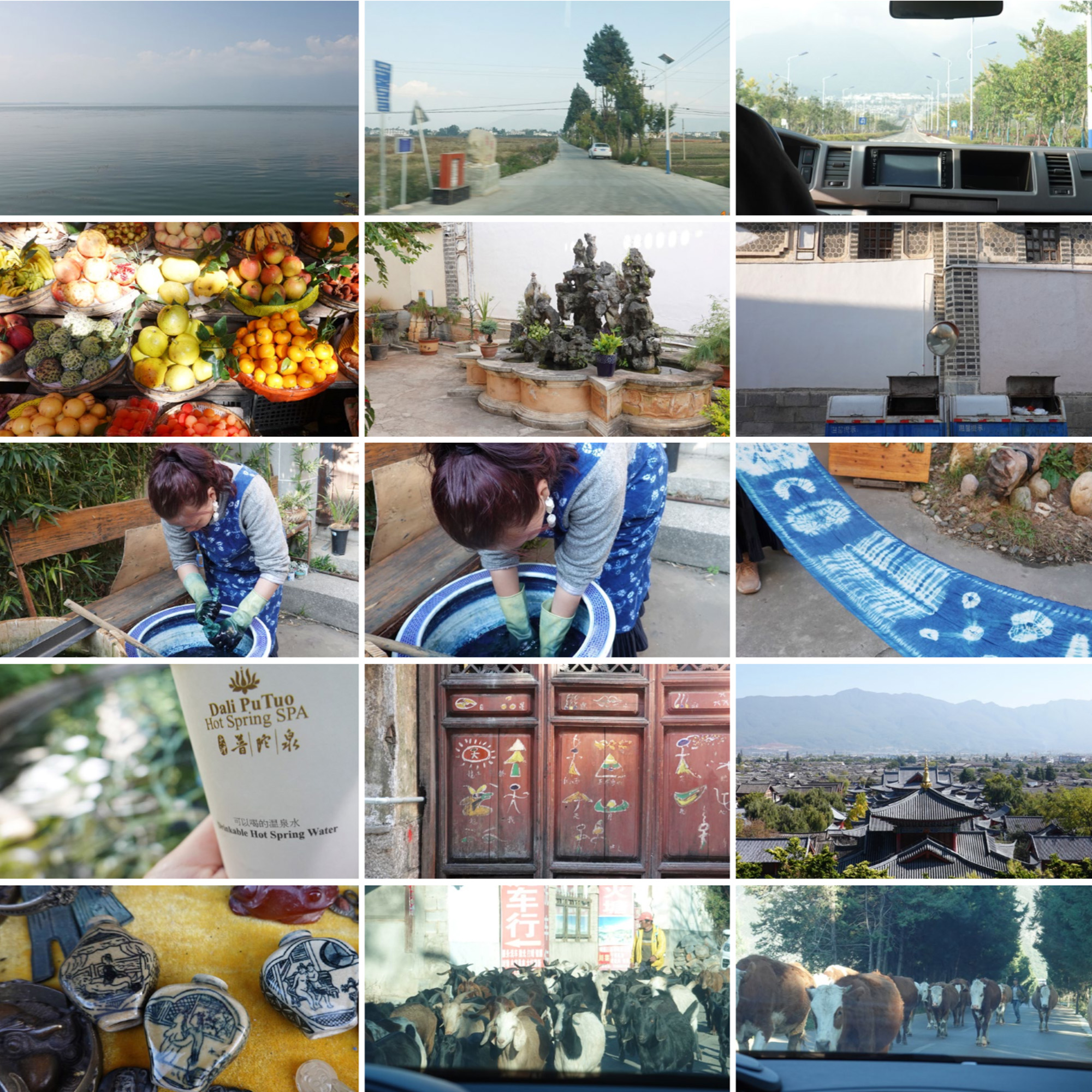

Images of Fei Arts Museum staff on vacation in Putuo, Zhoushan, as a result of GE YULU’s Holiday Times, 2020. Photo by Junjun, Xiling, and Xueying.

During your exhibition “Sometimes Doing Something Helps Nothing” at Guangzhou’s Fei Arts Museum, you took over the roles of three museum workers as part of the project Holiday Times, so they could take a rare holiday. As someone who has worked for art nonprofits for years, I have many first-hand experiences of losing work-life balance due to an intense workload. What is the feedback you received with this project, and would you want to implement it at other venues?

Oppression in museums is part of a systemic issue. Museums, such as Fei Arts, hope to organize the most influential exhibitions with the least cost, which inevitably overworks their staff. The unprofessionalism of artists and their abusive treatment of museum workers are deteriorating this working environment, too. Artists tend to only provide remote directions while the production of their work is completely handled by the museum, which leads to museum workers becoming their temporary assistants on top of their regular roles and responsibilities.

Thus, I decided to step out of my comfort zone and replace three museum employees during my exhibition, so that they can rest while I’m completing their tasks. People seem to have enjoyed this project, as there were nonstop discussions and new solutions proposed at the talks and workshops organized by the museum. Although the approach of Happy Times has limitations and may not be suitable for popularization on a bigger scale, I appreciate the creativity and authenticity that is deeply rooted in this practice of resistance.

I will not replicate this project elsewhere because it was not my intention to volunteer free labor for the benefit of the museum. What I truly hoped to challenge are the fixed roles and relationships within institutions. In fact, Fei Arts Museum did change. After this exhibition, I reflected on the problems I’ve observed and gave the museum feedback. The museum was willing to face some of the issues instead of holding onto previous modes of exhibition-making and personnel arrangements. For example, they agreed to curate more small-scale exhibitions that would give more curatorial freedom to non-managerial staff, enabling them to produce the programs as curators and be adequately credited for their work, instead of remaining as nameless individuals with no opportunity for creative input.

I feel very fortunate to see this project contributing to a virtuous circle. The staff are no longer just tools, or cogs in the machine, as they can see that their creative initiatives can now make the museum more impactful.