Soft Power, Hard Truths: An Interview with Pio Abad

By Nicole M. Nepomuceno

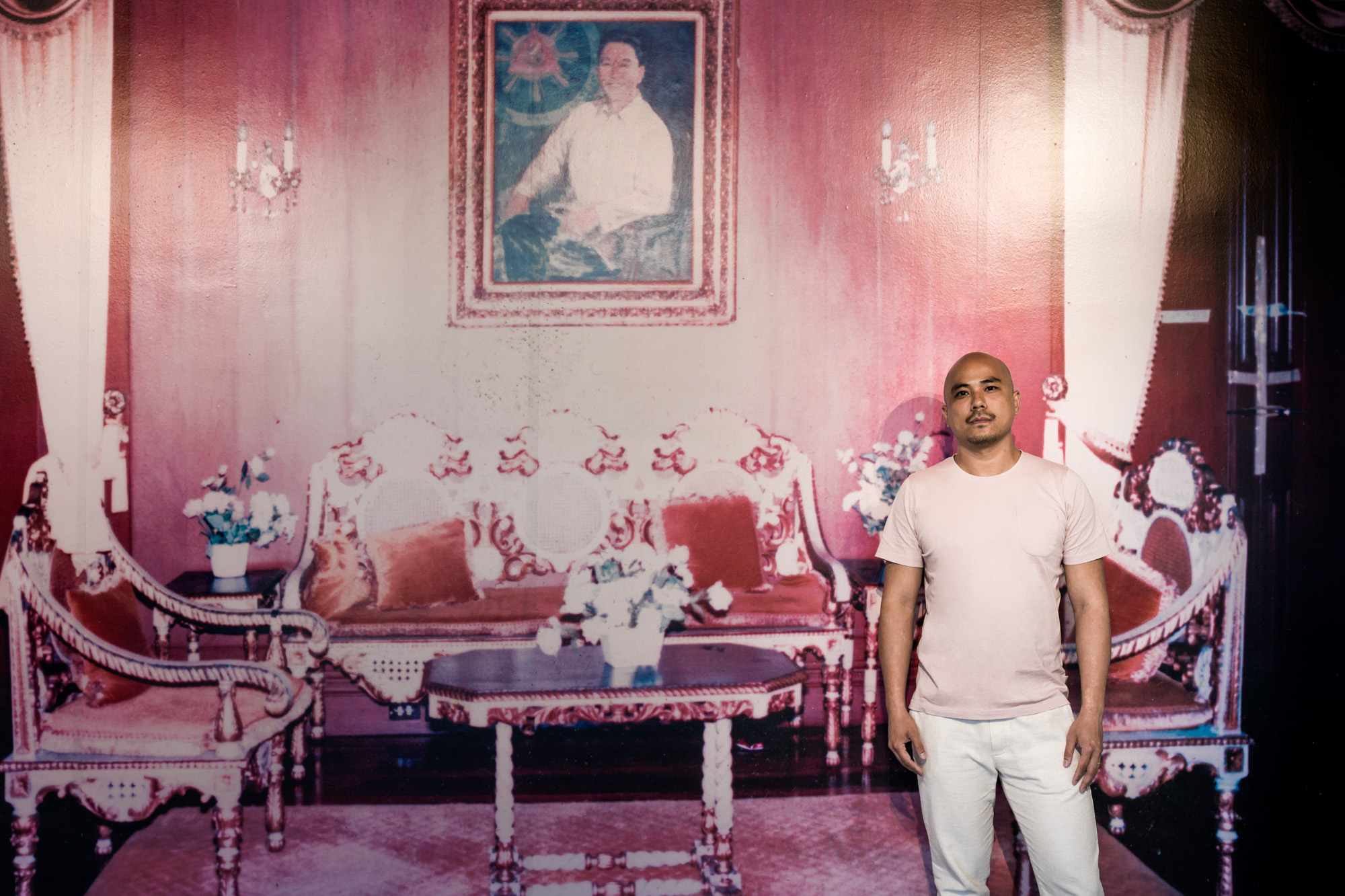

Portrait of PIO ABAD at "Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts," Ateneo Art Gallery, Manila, 2022. Courtesy the artist.

We often forget how difficult it is to remember. On June 30, 2022, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. was sworn in as president of the Philippines, 36 years after his father, the kleptocratic Ferdinand Marcos Sr., was deposed from his dictatorship and exiled to Hawai‘i. With more than 30 million ballots in favor of Marcos Jr., the 2022 election seemed to have reversed the sentiments of the 1986 People Power Revolution, the nonviolent popular movement that ended the elder Marcos’s 20-year rule and called for the reinstatement of democracy in the country.

After 1986, multiple pro-democracy presidencies failed to substantially raise the quality of life of the middle and working classes. This shortcoming, exacerbated by Marcos’s well-oiled social media misinformation campaign and the lack of nuanced study of the Marcos dictatorship in schools, allowed the former regime (1965–86) to be repackaged as a “golden age” of economic prosperity, culture, and infrastructural development. Its human rights violations, with at least 11,103 individuals who had been subject to involuntary detention, exile, torture, and murder, are erased or downplayed to highlight the economic growth of the administration’s early years—neglecting the recession suffered toward the end of the dictatorship. The success of this historical distortion operation provoked conversations on historical amnesia, soft power, and social media: How is it possible that a country could reelect the same autocratic family it chose to depose after merely two generations?

This time last year, when the Philippine presidential campaigns were in full swing, artist Pio Abad was in Manila for his exhibition “Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts” (April 19–August 6, 2022). There, he featured his ten-year multimedia project that illustrates the vastness of the Marcoses’ ill-gotten assets at Ateneo Art Gallery, from their “smuggled jewelry collection” to “the largest collection of English royal silverware in the world.” Our conversation last December recalled the historical shifts that occurred that year, with the privilege of distance as two members of the Filipino diaspora. Through Abad’s works, we discussed how the Marcoses have utilized culture to obscure their corruption and human rights violations; the 2022 grassroots organization that opposed the return of Marcos as president, also known as the Pink Movement; and the difficulty in remembering history within an environment of rampant misinformation.

Below is an extended version of my transcribed interview with Abad that was first published on January 1 as part of the ArtAsiaPacific Almanac 2023. In a similar way to how Abad’s practice is an exercise of remembering a history that is being actively erased, the process of transcribing, editing, and revisiting this text is my way of keeping myself from forgetting.

How would you describe the energy in Manila this year?

I was in Manila from March to May 2022 to do the show “Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts” at Ateneo Art Gallery. Coming back for the first time since 2018 was a bit of a shock because during my absence so many things have been upended. Former president Rodrigo Duterte had launched a full-scale attack on public discourse, from shutting down the media company ABS-CBN to arresting the journalist Maria Ressa along with other various voices of dissent.

It was a bit of a roller coaster before the May 9 presidential elections because, on the one hand, all signs were pointing to Ferdinand Marcos Jr. winning—and thereby winning this fight over history—but at the same time there was this incredible outpouring of support for his opponent, Leni Robredo. But the Pink campaign wasn’t even just about her, it was a movement to protect what we fought for in the 1986 People Power; it was a gathering of people who really wanted to fight for history, for whatever democracy we had left, done in such an incredibly creative way. A million people gathering in the streets is not something to dismiss, but to then realize it didn’t matter to the elections was incredibly painful because Marcos won by an outstanding majority.

I keep in touch with friends who have worked with Robredo’s campaign or are doing more grassroots activism. I observed a sense of despondency, because if a million people in the streets can be trampled by one of the most well-funded historical distortion campaigns, then what do you do? How do you fight it? I think that’s where people are: gathering their thoughts, nursing their wounds, and trying to work out where to go next. What was amazing was that normally Philippine politics is so personality-led, but for once in my lifetime it felt like it wasn’t about one person but an entire community of people who care about truth, democracy, freedom of expression, and how these values can be expressed through creative means. You can’t dismiss that. It’s there and that’s not going away.

Installation view of PIO ABAD‘s Forty pieces of silverware sequestered from Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos and sold by Christie’s on behalf of the Philippine Commission on Good Government from the series The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders, 2014, forty giclee prints on semigloss paper, mounted on dibond, dimensions variable. Photo by At Maculangan. Courtesy the artist.

Detail of FRANCES WADSWORTH JONES and PIO ABAD‘s Twenty-four reconstructions of pieces from the Hawaii Collection, modelled from photographs taken by Christie’s, 2019, from the series The Collection of Jane Ryan and William Saunders, 2012- , 3D printed plastic, brass and dry-transfer text, dimensions variable. Photo by Matthew Booth. Courtesy the artist and Ateneo Art Gallery.

“Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts” is the culmination of your ten-year multimedia project on the Marcos’s ill-gotten assets. Can you tell me more about your reproduction of the objects the family amassed and the act of remembering that history of corruption?

In its very essence, the show is a reconstruction of the Marcos loot through art: drawings, sculptures, 3D-printed works, text, paintings. And in reconstructing this loot-slash-collection, it becomes a way of inviting people to look at that history closely. Because the works, such as those in the series The Collection of Jane Ryan and William Saunders (2012– ), invite close inspection: the intricate, 3D-printed replicas of the Marcos’s smuggled jewelry collection that I made with my wife, Frances Wadsworth Jones; postcard prints of the family’s Old Masters collection that visitors can take with them; ink drawings of sumptuous furniture. I think one factor that contributed to widespread historical amnesia of the Marcoses’ theft is that their loot is so vast: USD 10 billion. They use art culture as a cloak of civility but it’s so outrageous: buying the entire contents of an Upper East Side apartment, buying a tiara that used to be owned by the Romanov family, or having the largest collection of English royal silverware in the world. The Marcoses also absolve themselves through their ostentation and narratives so outrageous that they can dissolve into fiction. It was important to me that this collection was presented as factual evidence.

The other aspect of the show is that it’s a response to a much more personal history. My mom passed away in 2017 and we had her wake at the Ateneo de Manila University. It was a place that meant a lot to her and my dad. Ateneo was where their advocacies as young activists were shaped in the 1970s, and during the growing threat of the Marcos dictatorship in the early ’80s that was where they were both held under campus arrest. My mother also taught there for a number of years. Since her passing, this project has been irrevocably tied to personal grief and it became important that it culminated at Ateneo.

The act of remembering plays a big role in the show and in your practice in general. Works such as The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders physically reproduce objects that are laden with the Marcoses’ kleptocracy. And the show at Ateneo acts as a reminder of the dictatorship and its reliance on soft power. How can we remember actively to ensure that we won’t forget?

I can only talk about this from the point of view of someone who makes things. For me, to remember history actively means to continue telling its story against all odds. The odds against us might be insurmountable, but we write and we draw. It sounds incredibly naïve, but it’s important that we commemorate histories that people in power want to erase or want to write over by insisting on what we know and how we lived through it, and by creating things that can communicate that history to a wider audience. This is a challenge when it comes to contemporary art because it’s still a rarefied audience but remembering is a very active thing to do and as an artist it’s in the very tactile nature of making that allows you to resist.

Why do you think it’s so easy to forget?

There are multiple reasons. One has always been education. The Marcos dictatorship was never committed to producing textbooks; history was never taught actively in public schools. There’s that lack of infrastructure to teach this history properly. And, for many Filipinos, life is difficult. In going through the day-to-day, history becomes a distant thing, or even an unnecessary thing—or even a distraction—and so the politics of patronage that allow you to earn a living but don’t necessarily give you freedom is a more convenient choice.

The third reason is there is so much dark money that is being spent to ensure that you forget. When you think about the role social media networks played in editing things out and literally changing Philippine history, and the role that money has played in disempowering people—that is probably the largest cause of historical amnesia. You open your phone and you’re being told historically distorted information because they worked out an algorithm to ensure that that’s all you see—how do you counter that? Disinformation is a machine that ensures that bad people stay in power while you remain disempowered but entertained.

PIO ABAD’s Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas before it was painted black after the events of November 18, 2016, 2012-2016, digitally printed canvas and faux gold bamboo frame, 180 × 117 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Installation view of PIO ABAD’s Portraits of Imelda as Maganda and Ferdinand as Malakas, painted black after the November 18, 2016, 2012-2016 at "Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts," Ateneo Art Gallery, Manila, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Silverlens.

Some works in the show address historical erasure through the act of erasing itself. Tell me more about the Portraits of Imelda as Maganda and Ferdinand as Malakas, painted black after November 18, 2016 (2012–16) and the series Silme and Gene (2022– ), which obscure either parts of or the entire image.

Imelda as Maganda, Ferdinand as Malakas are reproductions of two portraits commissioned by the couple which depict them as mythical figures Malakas (Strong) and Maganda (Beautiful), believed to be the first Filipinos who entered the world. The Marcoses hung the original portraits in their private chambers, showing how they have internalized this myth. In 2016, after Marcos was redesignated a hero, I decided to paint the paintings black.

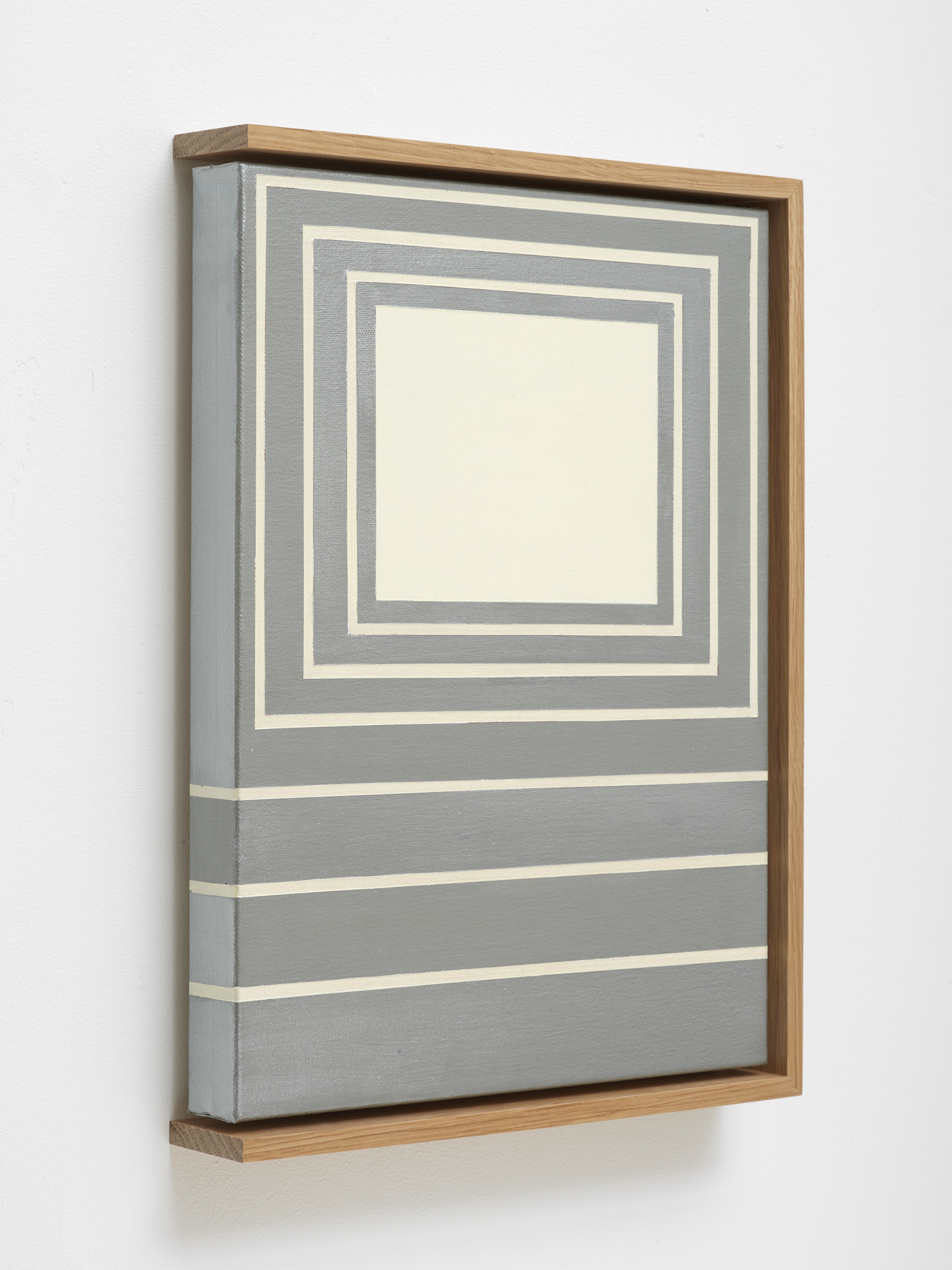

Silme and Gene are based on Marcos-era propaganda about dreaming of a new society, pamphlets they produced to distract people with this rhetoric of progress or change as a smokescreen for their kleptocracy. In my hands, these well-designed but ridiculous pamphlets are transformed into painted memorials for specific individuals who devoted their lives to fighting against these violent texts, these violent acts. I removed the propaganda texts, kept their designs, and renamed them after young democratic leaders Silme Domingo and Gene Viernes, as well as my mother Dina.

The two bodies of work are different but they are very much shaped by the same thing. I wanted to find a way to use erasure as a way of protest: if you can erase me, I will erase you back—literally. By erasing the Marcos portraits on the day that he was redesignated a hero by Duterte, there’s a strong element of wanting some kind of accountability to go with erasure. But at the same time, some poisonous texts do need to be erased. How do you then use that erasure as a way of commemoration? By taking away the texts on these propaganda in Silme and Gene and then re-appropriating them so each painting is named after someone who fought against the indoctrination, there is a sense of justice there as well, of doing right by people who have been forgotten or who are in the process of being erased.

PIO ABAD‘s For Dina II, 2022, acrylic on canvas in artist’s frame. Courtesy the artist.

How do you envision the future for your own practice?

I haven’t stopped making and I haven’t stopped dealing with this history. I might not sound particularly triumphant at the moment, but the very act of making art is an act of hope because you hope that there will be an audience for it who will take something from the work and turn it into something else.

One of the saddest but most hopeful moments during “Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts” was when the Pink Movement gathered at the Ateneo grounds after [the bulk of the ballots had been counted] and Marcos was clearly going to be the presidential winner. We opened the exhibition space so that people can come in. It wasn’t a very big space, but we had thousands of people all dressed in pink streaming into the galleries and just looking. The work became a site for people to grieve, to be angry, and to be confronted by history. A lot of young people were taking this in. They know how the world works in a way that my parents’ generation and my generation aren’t that attuned to, and I think there’s hope in that.

This is an extended version of the interview published in the ArtAsiaPacific Almanac 2023.

Nicole M. Nepomuceno was ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.