Recap: Hawai‘i Contemporary Art Summit 2021

By HG Masters

Screenshot of the keynote conversation between artist AI WEIWEI and the curatorial director of Hawai’i Triennial 2022, MELISSA CHIU, at Hawai’i Contemporary Art Summit 2021. Courtesy Hawai’i Contemporary.

Since the late 1980s, economists and politicians in Europe, North America, and Australasia have used the term “the Pacific Century” to describe the postwar growth of large East Asian economies and the shift in geopolitical power away from the countries of the Atlantic to those encircling the world’s largest ocean. This term—with all of its imperialistic political and cultural baggage, particularly in its revision of Henry Luce’s jingoistic 1941 declaration of the American Century before the United States entered World War II—is part of the title of the Hawai‘i Triennial 2022, “Pacific Century – E Ho‘omau no Moananuiākea.” As curatorial director Melissa Chiu explained at the Hawai‘i Contemporary Art Summit 2021 (February 10–13), in conversation with the Triennial’s associate directors Miwako Tezuka and Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick, “Pacific Century” will look at Hawai‘i as a midpoint culturally between the Asia Pacific and United States (sorry, Canada!), and would place the former region at the “forefront of our thinking.”

The aim of the Summit was to illustrate what that perspective might mean, and to that end, several days of livestreamed talks and Zoom discussions attempted to flesh out the curators’ research to date. The Summit occurred during the Lunar New Year holidays, and at very early hours in the morning Asia time, but organizers kept their recorded conversations online through the end of the month. However, in discursive terms and in its approach to the countries and cultures of Asia, it quickly became clear that the Summit’s imagined audience was located in the continental United States rather than the cultural communities in countries on the western rim of the Pacific.

Installation view of DREW BRODERICK‘s Billboard I (The sovereignty of the land is perpetuated in righteousness), 2017, vinyl banner and neon sign on support structure, 366 × 732 cm, at Honolulu Biennial, 2017. Photo by Christopher Rohrer. Courtesy Hawai’i Contemporary.

Though Chiu stated that the Triennial would not necessarily be about the shift in geopolitical power from the Atlantic to the Pacific, she did foreground the new nationalistic drumbeating of Cold War 2.0 that has kept the Asia-Pacific region on edge in the last decade. The Summit kicked off with a keynote conversation between Chiu—who is the director of the United States’ only national museum of art, the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC—and artist/activist Ai Weiwei. Chiu’s first question to Ai was about Cockroach (2020), his new documentary tribute to the 2019 Hong Kong protests, which have been instrumentalized by politicians and commentators on both sides of the Pacific as a proxy struggle between China and the United States and its allies, at the expense of local perspectives and the specific realities on the ground. But in his human-rights-campaigner mode, and as a victim of the Chinese Communist Party’s persecution himself, Ai tends to view situations in broad, civilizational strokes, and on this topic he was no different.

Screenshot of the conversation between KAPULANI LANDGRAF and MARK HAMASAKI of PILIAMO’O, at Hawai’i Contemporary Art Summit, 2021. Photo by kekahi wahi (Sancia Shiba Nash and Drew K. Broderick). Courtesy Hawai’i Contemporary.

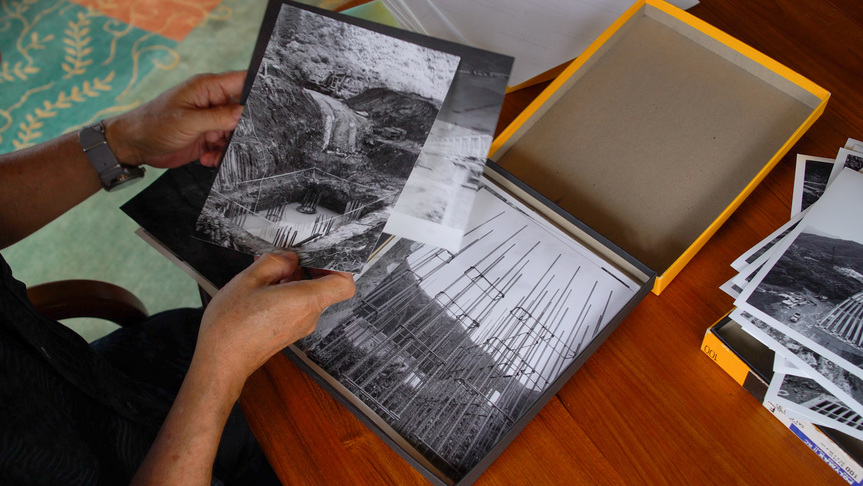

Detail of PILIAMO’O’s photographic documentation project into the construction of the H3 freeway in O’ahu. Photo by kekahi wahi (Sancia Shiba Nash and Drew K. Broderick). Courtesy Hawai’i Contemporary.

As a preview of the Triennial, the Summit felt most rooted and engaged through the perspectives of Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick, an artist and co-founder of the Honolulu art space SPF Projects. He said of the Triennial’s mission: “It is vital to challenge stereotypical representations of [Hawai‘i] and expose the violent legacies of settler colonialism and imperialism that lie beneath these false veneers of leisure.” One aim of the Triennial then is to move through colonial histories “to recenter on local, Indigenous knowledge.” To that end he refrained from translating the Hawaiian phrase in the exhibition title, “E Ho‘omau no Moananuiākea,” though he directed viewers to the online Hawaiian dictionary wehewehe.org. Videos featuring the poetry and literary-focused Elepaio Press’s cofounders Mark and Richard Hamasaki, as well as with the duo Piliāmo‘o (Mark Hamasaki and Kapulani Landgraf) about their photographic documentation project into the construction of the H3 freeway in Oʻahu, previewed the ways that the Triennial might dig into specific aspects of the island’s history of development, from cultural and environmental perspectives.

LEULI ESHRAGI, AOAULI, 2020, still from lecture-performance, digital artwork including video, image, sound, archive, at Hawai’i Contemporary Art Summit, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), Melbourne.

Beyond the Hawaiian islands, the Triennial’s interest in locating and tracing of interconnected cultures and histories of the Pacific are topics central to the practice of artist and curator Léuli Eshrāghi, whose Samoan-Cantonese-Persian ancestry informs his performative works about rituals of the body. In his lecture-performance, he read a letter from “the recent future of 2025” about his artworks made in 2020 that engage with ideas of kinship across gender and cultural boundaries. Addressing Indigenous conceptions of territory, the Karrabing Film Collective, the majority of whose members are Aboriginal inhabitants of the northern coast of Australia, was present in a recording by one of its founding members, Elizabeth A. Povinelli, a professor of anthropology and gender studies at Columbia University in New York. Using excerpts from their films, Povinelli wove a story about visiting Carisolo, Italy—where her father’s parents came from—with Karrabing members Linda, Rex, and Aidan. Povinelli compared the frontier disruptions to the clan systems of Carisolo to the establishment of European settlements in Darwin in 1865 and violent dispossession of Karrabing lands, noting the crucial difference that despite generations of discrimination, eventually her immigrant Italian family was able to insert itself into the formation of White America.

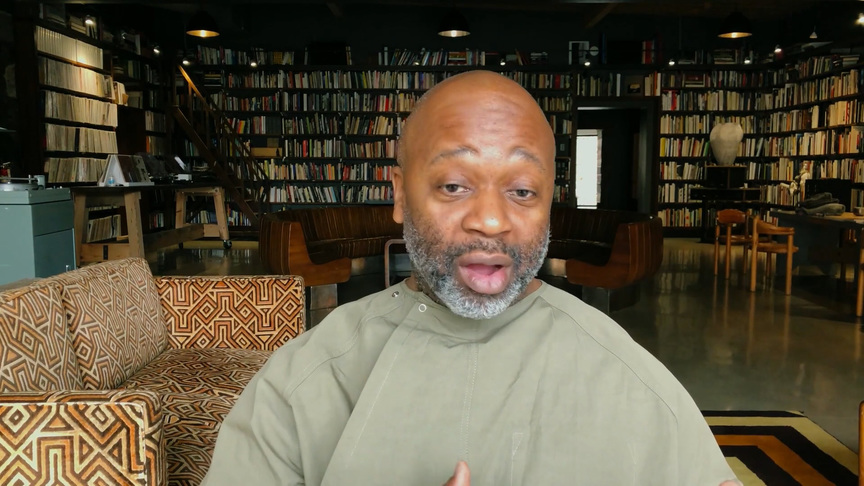

Screenshot of THEASTER GATES at Hawai’i Contemporary Art Summit, 2021. Image by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific.

THEASTER GATES, Afro-Ikebana, 2019, cast bronze, clay and tatami mats, 185 × 200 × 108 cm. Copyright the artist. Photo by Theo Christelis / White Cube. Courtesy White Cube, London / Hong Kong / New York / Paris / Palm Beach.

MIKA TAJIMA, Untitled (incense), 2019, handmade incense (basil, basil oil, cedar, frankincense, geranium oil, laurel, makko, pinon resin, Psilocybe cubensis, vetiver), dimensions variable. Copyright the artist. Courtesy the artist and Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles.

Screenshot of MIKA TAJIMA at Hawai’i Contemporary Art Summit, 2021. Image by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific.

In the keynote discussion, Miwako Tezuka, who is based in New York, noted that she had been doing an exercise of looking at the map of the world with the southern hemisphere on top, which, she said, “gives you a simulated ‘aha’ moment, when a brand new worldview opens up suddenly in front of you.” In the same way, some of most interesting threads of the Summit were from unexpected connections, like hearing from New York-based artist Mika Tajima about her interests in traditional Japanese crafts and new forms of artificial intelligence, and from Chicago-based Theaster Gates about his “Afro Mingei” projects, in which he connected the folk pottery of early modern Japan to the Black Art Movement of the 1960s and ’70s. Harvard professor Homi Bhabha recollected with delight encountering a bronze sculpture of Mahatma Gandhi at one end of Waikiki beach, a mark of the “inbetweenness” of the Sindhi community that had come to the island in the 1950s. In these conversations, Hawai‘i, and the Pacific more broadly, become a meeting point for cross-cultural journeys and intersections.

Mahatma Gandhi’s sculpture in Waikiki. Photo by Salvatore S. Lanzilotti / SS Lanzilotti Photography. Screenshot by HG Masters for ArtAsiaPacific.

One other salient thread that ran through several conversations was the cultural moment (and movements) of the 1990s, which is when the emerging idea of the Pacific Century was gaining recognition. The period coincided with Ai Weiwei’s decision to make art back in Beijing after more than a decade in New York; Broderick’s mention of the book Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Culture (1990), which Chiu cited as her “bible” in university; and in Chiu’s conversation with Bhabha, where they discussed his involvement with the iconic 1993 Whitney Biennial in New York that injected identity politics into the center of the city’s commercially oriented art scene. But the difference between then and now, Bhabha observed, is that identity politics has been weaponized by ethno-nationalists in charge of many countries, which is forcing minority communities into identitarian positions. Instead, Bhabha proposed, we should work for a broader solidarity based on interests, rather than identities, as a platform for progress in the 21st century. It will be interesting to see how the Triennial tackles this and other cultural topics around the Pacific, and whether it can really escape the heavy influence of the East Coast, Atlantic Ocean perspectives on Asia seen from a distance.

HG Masters is the deputy publisher and deputy editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

The Hawai‘i Contemporary Art Summit ran from February 10 to 13, 2021.