Guest, Worker

By Matt Hanson

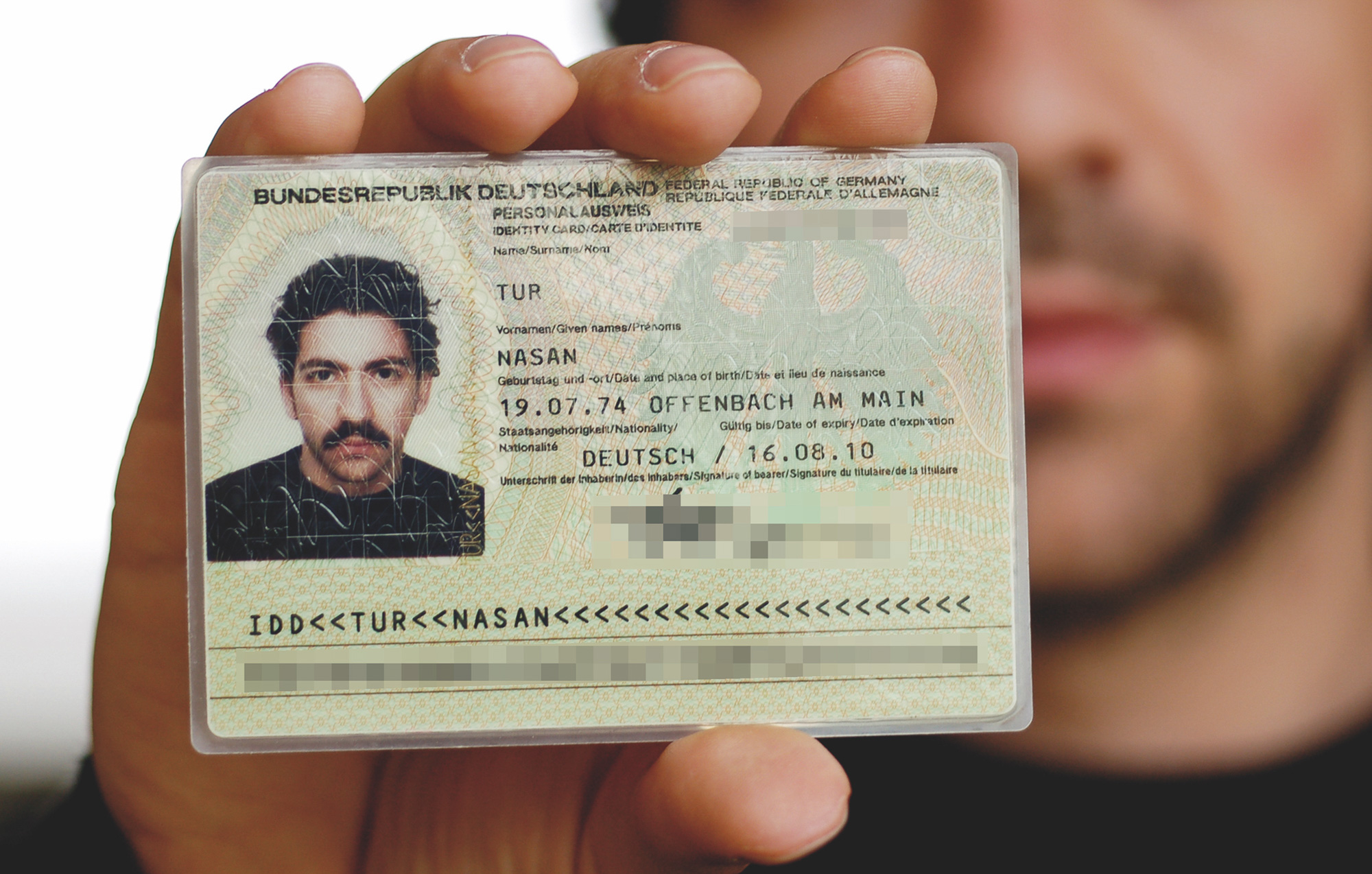

NASAN TUR, Self Portrait, 2000, c-print with actual federal ID card, 7 × 10 cm. Copyright Artists Rights Society, New York/VG-Bildkunst, Bonn. Courtesy the artist.

In need of a sizable labor force to boost its postwar economy, West Germany signed a Recruitment Agreement with Turkey in 1961, ushering in waves of Turkish "guest workers.” Though the arrangement lasted only 12 years, until the 1973 global oil crisis, the contributions and cultures of these migrant laborers remain ingrained in and vital to Germany today.

In 2021, to mark the Agreement’s 60th anniversary, a series of projects revisited this period of history, examining the workers’ confrontation with racism in Germany, and the sociopolitical conditions, such as gender oppression, that spurred their exodus from their home country.

Three creative productions in particular revealed comparative insights about workers’ experiences from Anatolia to the Rhineland since the mid-20th century: “Thorn Shelter,” a group exhibition at Istanbul’s Depo art space, Peter Chametzky’s book Turks, Jews and Other Germans in Contemporary Art (2021), and the “Intimacy of Longing” mixtape project by DJ and anthropologist Kornelia Binicewicz.

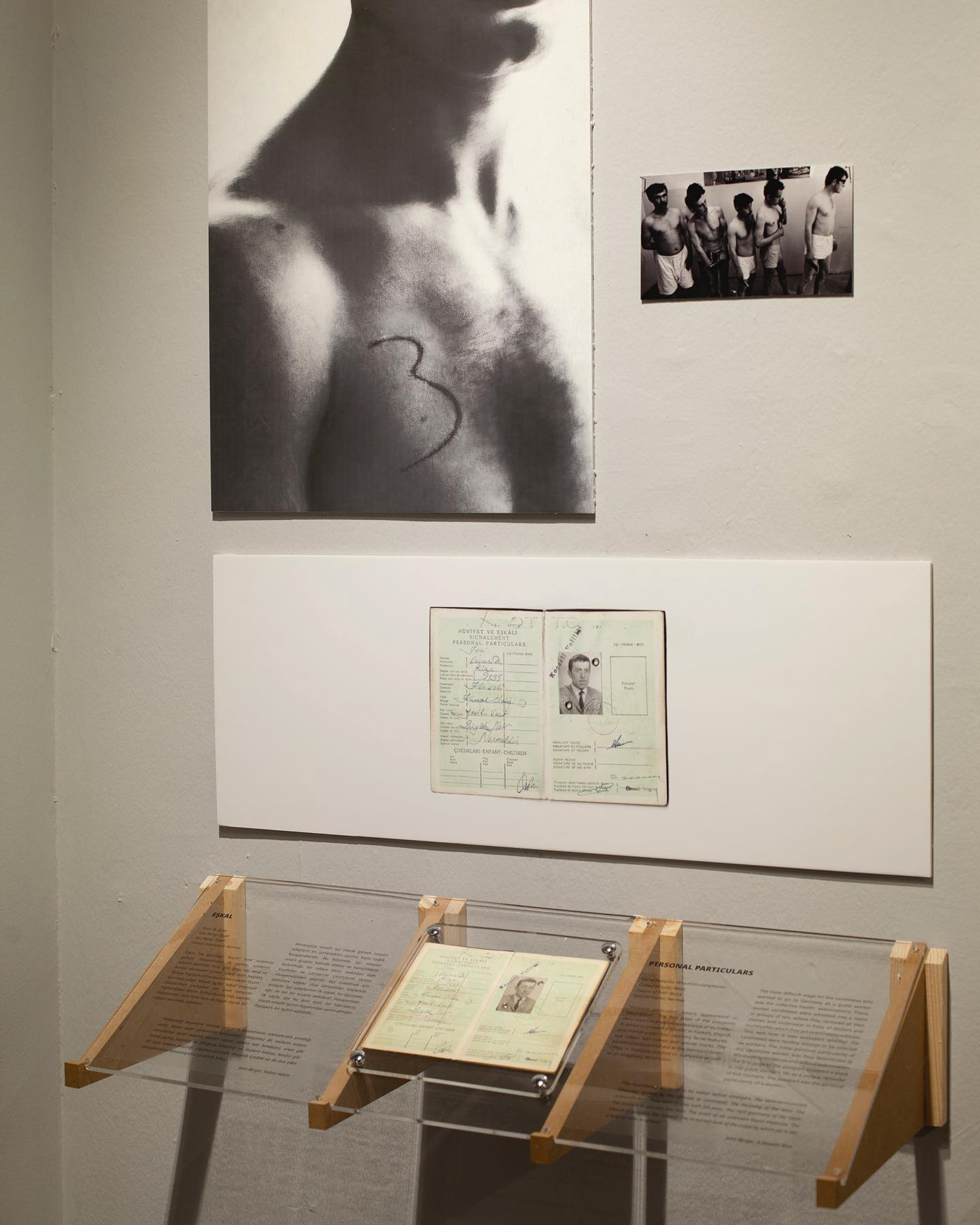

Installation view of DIASPORATURK’s Passport, 2021, workers’ passports and images from the archive of DiasporaTurk, dimensions variable, at "Thorn Shelter," Depo, Istanbul, 2021. Courtesy Depo, Istanbul.

“Thorn Shelter” opened in the former tobacco warehouse that is the patrimony of Osman Kavala, who has chaired the space from jail since 2017. The show began with an archival reel from Yugoslav Black Wave filmmaker Želimir Žilnik, and included research-intensive projects by Turkish artists Özlem Sarıyıldız, Cana Bilir-Meier, and collectives bi’bak and DiasporaTürk. Evincing that history was “quietly in the making” was DiasporaTürk’s installation Passport (2021), of travel documents issued by the German government for Turkish guest workers. These passports set a strange precedent for identity papers with their inclusion of the categorical term “worker.” The installation also incorporated photographic and documentary evidence of how closely Turkish laborers were scrutinized according to their physiological traits. Their bodies enumerated, standing in line in nothing but their underwear, individuals were itemized based on their “wheat”-hued faces, black eyes, or, most peculiarly, “normal” characteristics. This mass indexing of subordinated people evokes the unfinished denazification of postwar Germany, which was still reeling from the Holocaust in the 1960s.

In his exhaustive book Turks, Jews and Other Germans in Contemporary Art, Chametzky similarly argues that, as Germany’s largest ethnic minority group before and after the Second World War, Turkish guest workers were stigmatized, much like Jews. Among the artists that Chametzky profiles is the Turkish-German Nasan Tur. In his photographic Self-Portrait (2000), a clean-shaven Tur is seen holding up to the camera his German identification card, on which he appears with a mustache. He had deliberately grown out his facial hair to appear like the cliché unassimilated Turk before renewing his ID. Tur’s photograph of his ID portrait is, as Chametzky analyzes, a performative act, capturing the permanent transience of immigrants as racialized and objectified bodies. Although born in Germany, Tur is among the nation’s 800,000 non-German residents who became German citizens between the years 2000 and 2005.

FATIH KURCEREN, from the series Pithead, 2015, c-print, 56 × 71 cm. Courtesy the artist.

In the book’s second chapter, “Bodies,” Chametzky goes on to discuss Turkish-German artist Fatih Kurçeren’s photo series Pithead (2015), which captures immigrants of color and working-class ethnic Germans in Ruhr, a mining region. Unlike the historical focus of DiasporaTürk’s government-issued ephemera in “Thorn Shelter,” Tur and Kurçeren draw attention to the still sizable chasm between their communities and those whom Chametzky problematically refers to as “German Germans” (read: “White”).

That is not to say that present-day perspectives were missing at the “Thorn Shelter” exhibition. Sarıyıldız’s video Look, Listen Carefully (2021) shows three working-class women reflecting on their migration to Germany. One woman with shoulder-length gray hair, sat on an antique chair in front of a wall of paintings, explains how other migrants knew to bring their cookware, even food, but she did not. She relied on helpful friends. All three stress their poverty, their naivety, their nostalgia for Turkey, and their hopes to reunite with their families. Nevertheless, Look, Listen Carefully also alludes to the freedoms that women guest workers experienced in Germany, with one interviewee remembering how wider streets and a greater diversity of products in local markets led to her socioeconomic betterment, compared to her more modest and restricted life back in Turkey.

OZLEM SARIYILDIZ, Look, Listen Carefully, 2021, still from single-channel video: 48 min 29 sec. Courtesy Depo, Istanbul.

Delving further into gender dynamics and offering more substantial historical context to the video’s testimonies is the “Intimacy of Longing” initiative, which comprises texts, illustrations, and a mixtape arranged by Binicewicz. As part of her research, Binicewicz spoke with Turkish women migrants in Germany with the help of interviewer Aysel Aycan Aktaş, and probed the fact that one out of every three Turkish guest workers was female. Taking into consideration the different class backgrounds of these women, Binicewicz reasons that, for some of these migrants, working in Germany was not so much about making more money as it was about living free from Turkey’s patriarchal oppression.

Yearnings for female emancipation are embedded in the songs on the mixtape. For example, featured is “Almanya’da Ölenler” (1972) by singer Yüksel Özkasap who, unmarried and educated, became the “Nightingale of Cologne” after emigrating to Germany in 1966. The title of the track translates to “People Who Died in Germany,” expressing the sadness of many first-generation migrants in the 1960s over what they imagined, often rightly, to be their terminal expatriation. The lyrics also whisper of domestic abuse. “Germany, they say, it wouldn't have happened / Our funeral is also found on Turkish soil.”

Records and cassettes from the "Intimacy of Longing" project. Courtesy Ladies on Records.

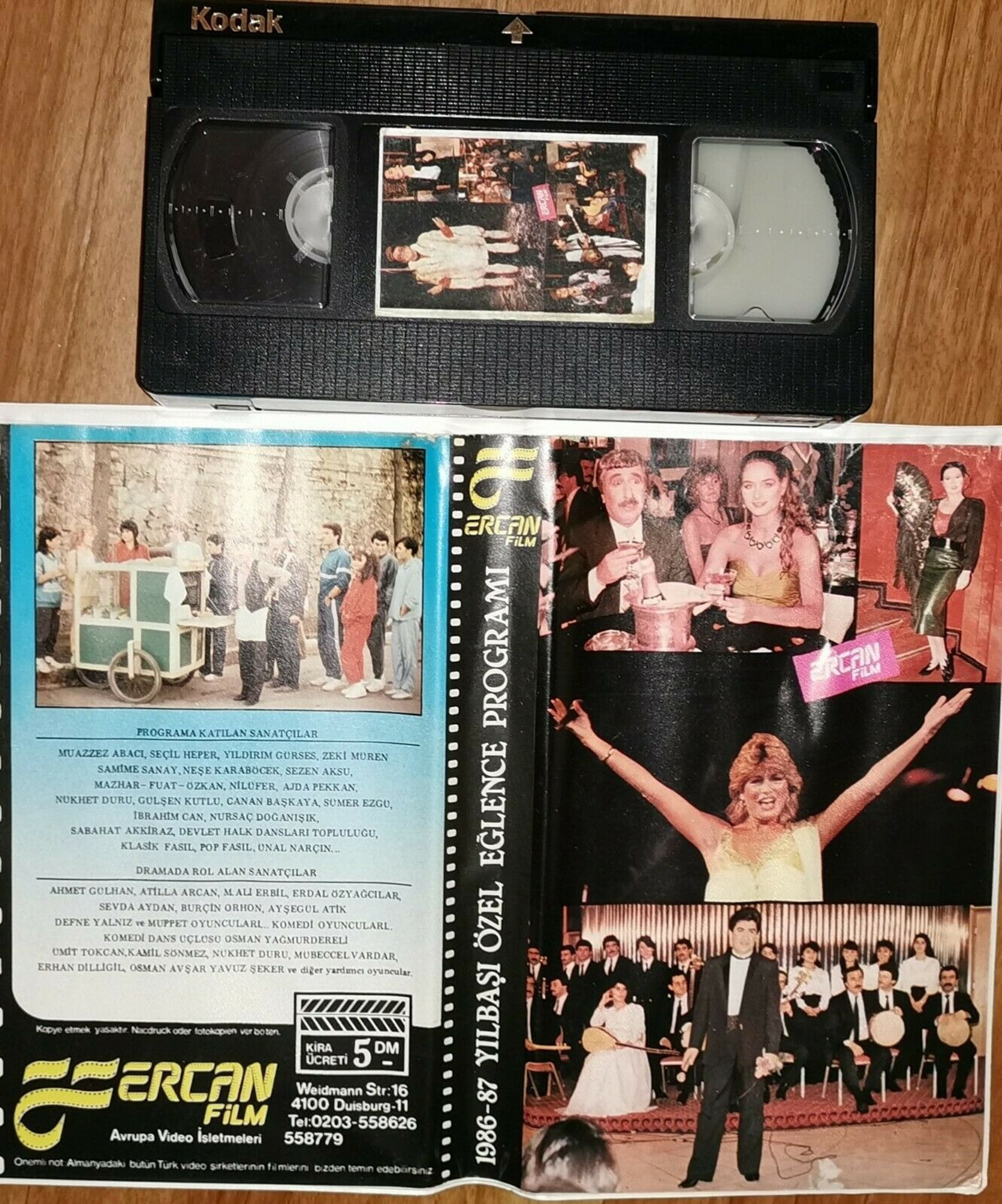

In the text component of “Intimacy of Longing,” Binicewicz expands on another facet of Turkish immigrant culture, with reference to the research of author Martin Greve, who found, in 1982, that every third Turkish resident in Germany had a VHS, a key way to access Turkish content. Likewise foregrounding the importance of the medium, bi’bak installed a vitrine at “Thorn Shelter” filled with Turkish VHS tapes produced in Germany, many of which are titled “expatriate pain” (in Turkish, “gurbet acısı”). Behind this assemblage was bi’bak’s video installation Please Rewind (2019), which evidences the thorny project of Turkish integration into German media culture, such as when a blonde anchorwoman presents a glamorous television program of Arabesque musical dramas from eastern Anatolia. The multiculturalism that Turkish guest workers instilled in Germany directly challenged Eurocentric racism and Turkish sexism.

When the angst of expatriation became too much to bear, a Turkish family might have piled into a Volkswagen and hit Europastraße 5, a 3,000-kilometer highway through Austria, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria. Binicewicz found that their road trips from Turkey to Germany and back provided ample opportunity to turn up the car stereo and blast tracks like “Almanya Acı Vatan” (1979) by Ruhi Su, translating to “Germany, the Bitter Land” (also a 1979 film).

GIZEM WINTER’s digital illustration for the "Intimacy of Longing" project. Courtesy Ladies on Records.

Another video work by bi’bak at “Thorn Shelter,” Sıla Yolu (2016–17) relays testimonies of the journey from Germany to Turkey, which took at least two days. The collective cast a somber light on the topic by focusing on roadside memorials. Migration was life-threatening for Turkish guest workers unused to long-distance travel, especially via the closed communist society of Yugoslavia, where many drivers kept their windows shut the whole way out of fear.

Perhaps not much has changed since the 1961 Agreement. Germany still grants citizenship mostly based on genealogy as opposed to territorial birth. And, facing the difficulties of life as an immigrant head on, Turkish citizens continue to move to Germany. In “Thorn Shelter,” Sarıyıldız’s multichannel video Welcomed to Germany? (2018) splices together nine interviews with Turkish people who recently emigrated to Germany for reasons ranging from better job opportunities to state violence. What transpires is the traumatic urgency of their exilic loss.

OZLEM SARIYILDIZ, Welcomed To Germany?, 2018, still from single-channel video: 25 min. Courtesy Depo, Istanbul.

Despite this, what can be found in all three projects is a sense of migrants’ resistance against injustice. In “Thorn Shelter” was the film Semra Ertan (2013) and the audio installation Her Own Voice (2016), Bilir-Meier’s homages to her aunt, the poet Semra Ertan, who set herself aflame in Hamburg protesting racism against Turkish guest workers. Beside these works, the show included a newly published, Turkish-German edition of Ertan’s poems, which recall the enraged disquiet in the musical lyrics catalogued in “Intimacy of Longing,” such as those by Afro-Turkish singer Esmeray. “Go back to your home, they say,” Ertan wrote in her poem "My Name is Foreigner” (1981), echoing themes in Esmeray’s song “13,5” (1975), when she sang, “May my color always be black, so long as my heart is not.”

In turn, Esmeray’s anti-racist music resonates with the artwork and scholarship of the Afro-German luminaries that Chametzky writes about, including the pioneering intellectual of Afro-German studies May Ayim (whose death by suicide mirrored that of Ertan), and Mwangi Hutter, a duo whose works harness their African and German identities. Standing in solidarity, these cultural laborers humanize and critique the artifices of national exclusivity through their art and lives.