Diane Severin Nguyen: In Her Time (Iris’s Version)

By Coco Zhou

DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN, In Her Time (Iris’s Version), still from video: 67 min. Courtesy the artist.

For decades, China has tried to build a cohesive national identity among its citizens despite uneven economic development and rising inequality. But when nationalism and neoliberalism conspire to determine social value, how can one’s mundane aspirations of recognition and transformation—of “becoming somebody”—be understood? This question, which explores tensions between uniformity and uniqueness, between institutionalized history and individual narrative, forms the center of In Her Time (Iris’ s Version), a new feature-length film by Diane Severin Nguyen. The work is currently showing as part of the 2024 Whitney Biennial and at Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery, while a previous edit, In Her Time, debuted in 2023 at Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum.

In Her Time (Iris’ s Version) follows an actress, Iris, preparing for her first lead role in a historical film about the Nanjing Massacre, a horrific series of murders and torture after the Japanese invasion of China during the Second World War. Through this filmographic inception, Nguyen captures the mechanism of how trauma is recalled and recognized somatically; how it vaguely activates specific sensuous memories and reconstructs an individual past. Ideologically, this process can also be used as a tool for nation-building, encoding violent events with collective moral significance.

DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN, In Her Time (Iris’s Version), still from video: 67 min. Courtesy the artist.

Nguyen immediately establishes the illusionary, dreamlike nature of repressed traumatic events. Toward the film’s beginning, the protagonist looks out the window at her backdrop—flashing signs and a Ferris wheel—and remarks, “It’s like a fairyland.” This place, Hengdian World Studios, is no ordinary theme park. Claiming to be the nation's largest film and television shooting base, it amalgamates architectural replicas that evoke various eras in Chinese history. Hundreds of thousands of aspiring actors known as hengpiao, or Hengdian drifters, have come here for work in the past two decades, recruited into the mass production of historical dramas under the state’s mandate of reclaiming Chinese history and promoting national unity.

Formally, In Her Time (Iris’s Version) draws on the documentary format. Using realistic and intimate staging, there are scenes of rehearsal, roleplaying, and confessionals in a car and living room where Iris speaks to the camera and answers interview questions. Yet, the film also defies the genre by providing no overarching narrative or explanation besides the glimpses Iris offers into her thinking and journey. Indeed, while it reenacts scenes from the Nanjing Massacre, In Her Time is deliberately vague about the event, which remains unidentified until one scene, where Iris reads a book whose cover unveils the historical film’s subject. Instead, recurring imagery like mangosteens being crushed, or a rifle poking through bubbles and beaded curtains, metaphorically portray the acts of historical violence.

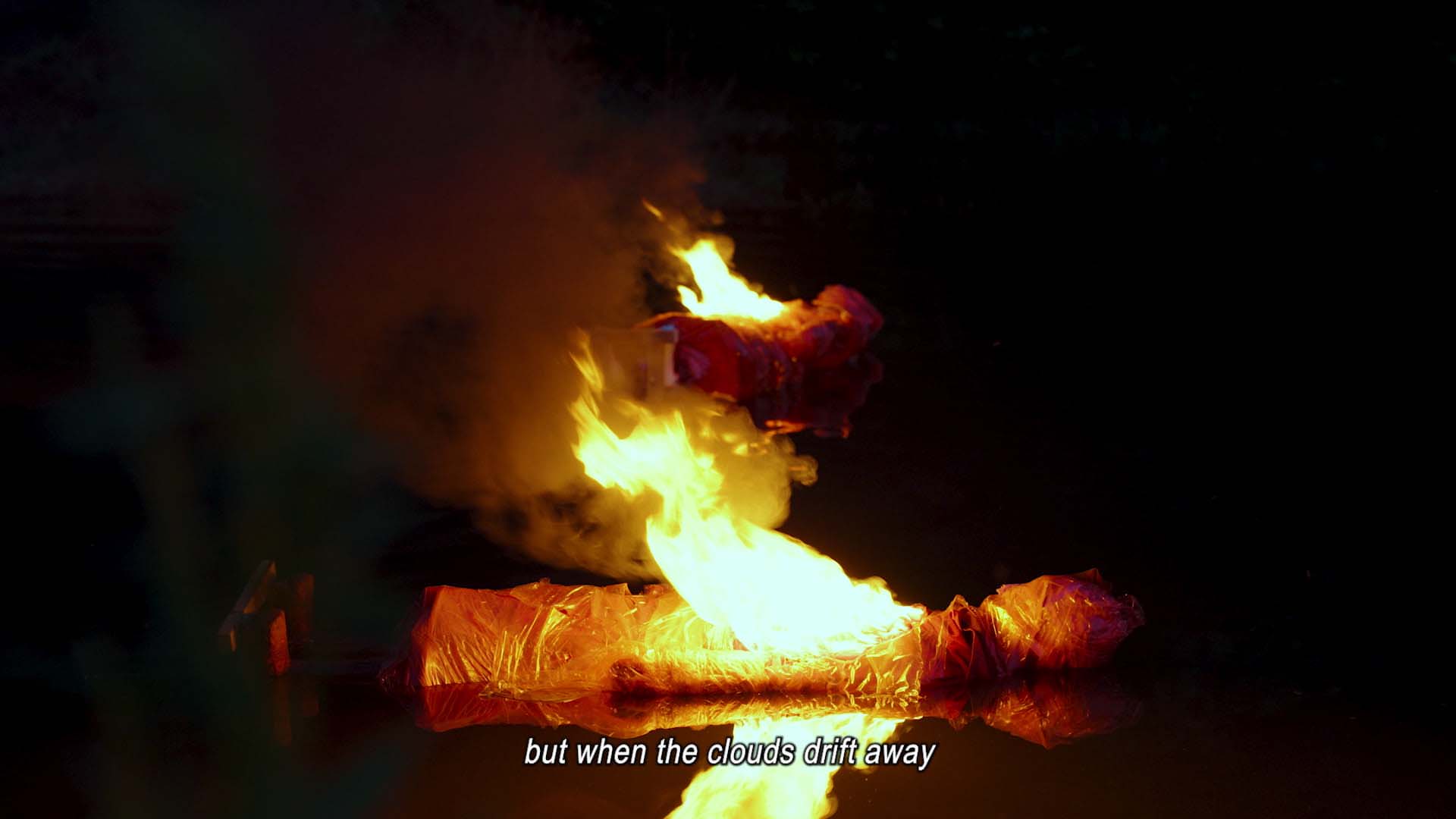

DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN, In Her Time (Iris’s Version), still from video: 67 min. Courtesy the artist.

Nguyen’s emphasis on the objects’ sensuous textures recalls her past photographic works. In her 2021 film If Revolution Is a Sickness, Nguyen uses pop music and youth culture to explore how material symbols and bodily rhythms inform national identity in postrevolutionary Poland. In her current work, she continues that investigation by presenting an actress’s struggle as a woman in the Chinese film industry, centering on the bruised juncture where nationalist ideology meets personal aspirations. Such themes linger within the popular Chinese historical film genre about the Nanjing Massacre (and other instances of national trauma), which follows a set of conventions depicting the heroism of individuals who sacrifice personal happiness for patriotic duty. As cultural critic Rey Chow observes, these films tend to feature willful women whose desires are “redirected and reincorporated into the social and communal fabric.”

In a scene-within-scene that re-enacts the emotional climax of the Massacre in In Her Time (Iris’ Version), Iris clutches a child tightly to her chest while surrounded by imperial Japanese soldiers in a confetti shower; at the same time, the camera spins in a dizzying display. Here, the odd appearance of confetti exposes how such popular films turn women into representations of a nation in crisis while making their virtuous suffering appear glamorous. With its playful irony, Nyugen’s intervention reroutes the usually straightforward emotion that the genre promises: a feeling of righteous rage, pity, or empowerment that confirms one’s belonging to a nation—an imagined community materialized through such emotions.

Installation view of DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN‘s In Her Time (Iris’s Version), still from video: 67 min, at "Diane Severin Nguyen: If I hadn’t created my own world, I would have died in someone else’s," Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG), Vancouver, 2024. Photo by Rachel Topham Photography. Courtesy CAG.

Instead of offering a transparent critique, In Her Time (Iris’ Version) uses the mise-en-scene to shed light on alternate readings. In one rehearsal scene, Iris paces underneath the Ferris wheel while practicing a line about freedom “being a struggle to fly upwards.” As she experiments with cadence and tries to deliver the appropriate tone, what sounds like a resolution is made ambiguous by the slow-turning Ferris wheel in the background, animating the cyclical nature of “resolution” in modern Chinese history.

One could also read the line as a double entendre, as optimism for the war’s end and the post-1980s economic liberalization in China and beyond. After all, the struggle for freedom from occupation has become one of achieving economic freedom through upward mobility. The latter is perhaps more relevant to Iris’s lived experience, as, after China deindustrialized, traditional wage-labor forms like factory work became increasingly unattainable. More citizens seek gig work, which sells flexibility as freedom despite slashed benefits and minimal protection. In creative industries that rely on workers’ dreams for self-actualization, getting paid while “doing what one loves” has created additional appeal. In Her Time hints at how these labor conditions feed off individual aspirations: smiling at the camera, Iris explains in one interview scene that she is excited to finally have a role with dialogue. Later, she muses that her work—performing authentic emotions and embodying different characters—makes her feel most alive.

Shedding light on the relation between the systemic and the personal, In Her Time (Iris’ s Version) offers a case study on how individuals cope and bargain with the known reality of their exploitation. In one scene, a collage of magazine and newspaper cutouts featuring famous Hong Kong and Hollywood actresses is shown by Iris’s bed. But while these images demonstrate she is aspirational, Iris is not naive. She often questions the motivations of her audiences, suspecting that Chinese viewers want to see a Nanjing Massacre story of dying women while assuming North American viewers would not differentiate between Chinese and Japanese characters. She also inhabits fantasies of reverse role-playing, aiming a rifle at a teddy bear she carries from set to set, then crying over it melodramatically during those practices. Iris is thus realistic in her optimism, knowing that it will not save her from structural subordination. Rather, she acts repeatedly for the pleasure of becoming someone other than herself. Perhaps her optimism makes her realistic, for it sustains her attachment to the world of precarity and objectification while keeping despair away.

DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN, In Her Time (Iris’s Version), still from video: 67 min. Courtesy the artist.

Iris’s realism could thus be considered a political strategy, induced by an awareness of her social position. Feminist scholars have identified this phenomenon in China, where the state mobilizes images of women’s suffering in its cultivation of nationalism, all the while retaining tight control over the feminist movement. For Chinese feminist activist and writer Lü Pin, because dreams of reform and revolution are likely to shatter under authoritarian rule, it matters more to focus on the ordinary ways that people may live a meaningful life and connect with others; so that they may “contribute to changes not yet envisioned,” however and whenever possible. In this context the “crisis ordinariness,” as positioned by theorist Lauren Berlant, gives rise to unintentional tactics of adaptation and negotiation rather than complete retreat or refusal. Such tactics become a means of staying undefeated amid an impossible situation, of retaining hope when faced with totalizing oppression.

Accordingly, by the end of the film, when Iris declares “If I hadn’t created my own world, I would have died in someone else’s,” her statement registers as somewhere between a heroic assertion of personhood and a trauma response. This is not to minimize the latter as a mode of survival, but to point out the mundanity of trauma under China’s current socioeconomic conditions. However, neither analysis conveys the whole story, at least if one believes that historical subjects are not doomed for re-enactment. With its unsettling ambivalence, In Her Time (Iris’ s Version) resists becoming a portrayal of victimhood that audiences can feel morally superior toward. Rather, it forces viewers to expand definitions of political agency to include grandeur, impactful actions, and ordinary activities. For, longing, bargaining, fantasizing, and adapting all express a will to live—and in the face of trauma, that too is revolutionary.

Installation view of DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN‘s In Her Time (Iris’s Version), still from video: 67 min, at "Diane Severin Nguyen: If I hadn’t created my own world, I would have died in someone else’s," Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG), Vancouver, 2024. Photo by Rachel Topham Photography. Courtesy CAG.