Life, Through the Frame of Kok Yew Puah

By Lim Sheau Yun

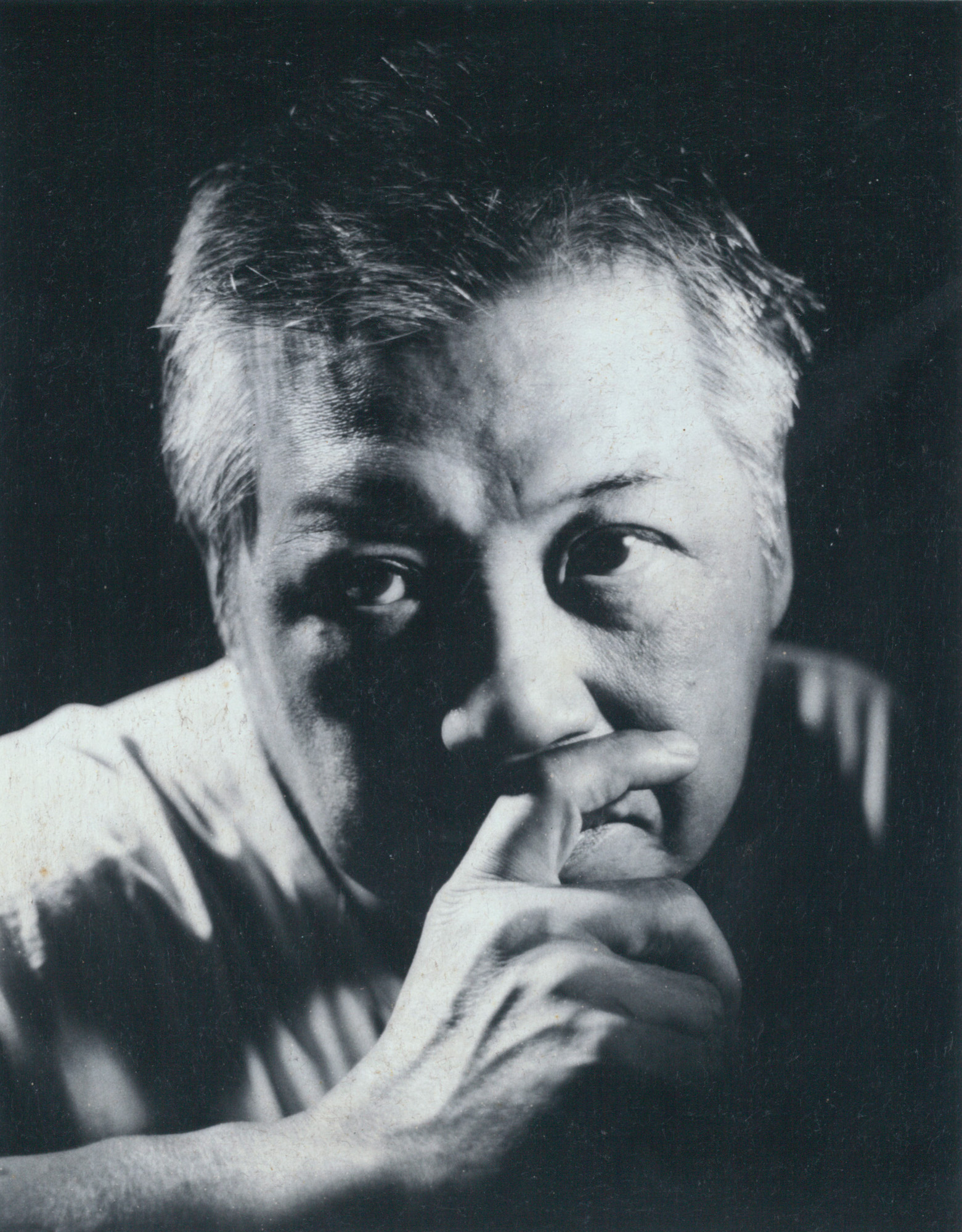

Portrait of KOK YEW PUAH. Photo by Yeh Poh Chung. All images courtesy Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur.

In the 1950s, Marcel Duchamp infamously derided “retinal art,” rejecting the lowly pleasure of the eye. Instead, he advocated conceptual art, which he claimed was “in the service of the mind.” “The retinal shudder!” he exclaimed in a 1951 interview. “Kok Yew Puah: Portrait of a Malaysian Artist” shuddered and exclaimed with the joy of the retinal. The retrospective, presented at Ilham Gallery in Kuala Lumpur, noted the timbres and transformations of Puah’s eyes—including his attempts in his early years to rationalize sight with experiments in abstraction, the subsequent development of his cheeky realism, and the fusing of his eyes with the lens of the camera. Never mind the mind, it was a feast for eyes long stuck behind screens.

Born in Klang, Selangor, Kok Yew “George” Puah (1947–1999) had two professional lives. The son of a business family, he studied at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School in Melbourne. There, he was introduced to abstraction and pop art, and made screen prints in bright purples, greens, and oranges. However, shortly after his return to Port Klang in the early 1970s, he gave up on art and took over his family’s business—Life Chili Sauce, whose sauce packets are today ubiquitous in KFCs all over Malaysia. Life’s success as a brand was not due to Puah’s efforts, but rather in spite of them: in the 1980s, Puah returned to art after a 12-year hiatus, having slowly run the family business into the red. This time, he turned to the paintbrush instead of the printmaking screen.

Installation view of "Kok Yew Puah: Portrait of a Malaysian Artist" at Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, 2022. Photo by Kenta Chai.

While it is tempting to see Puah’s artistic career as comprising two distinct phases—before Life and after Life—the proclivities encapsulated in his early screen-printing experiments echo throughout his practice. His early silkscreens play with the relationship between Platonic forms—squares and circles feature extensively with variations and dissolutions. In an untitled print from the 1970s, four squares, each containing more concentric squares, are skewed in mockery of the planes of a room in an imperfect one-point perspective. Two opposing “walls” are rendered in bright red, orange, and yellow, while the back “wall” appears in blue and gray, and the “floor” is treated with ochre lines. While the planes are all suspended in the same dark-green void, each one also exists independently, with a different vanishing point. Instead of fixing on a single horizon with an immobile eye, viewers are subtly forced to continuously relocate their gaze. This print is less a room than a deliberation of the traditional mechanics of a room’s geometric construction: quite simply, planes brought in proximity on a field suggesting space. Flatness and dimension are twin poles.

Puah’s post-hiatus paintings investigate similar formal possibilities of color, space, and illusion, albeit with a new interest in the subject matter of the known, phenomenal world instead of the rational, abstract one. Having encountered and been deeply inspired by the works of painter and printmaker David Hockney, Puah assembled an iconography of his hometown, Klang. Thoroughfares, road signs, and neighborhood kids were to Puah’s Klang what swimming pools and fancy friends were to Hockney’s California.

KOK YEW PUAH, Urban Playground, 1994, acrylic on canvas, 139 × 185 cm.

Through his paintings and drawings, Puah chronicled his ambivalence about Klang’s transforming landscape amid the rapid economic development of the 1980s and ’90s. The Ilham exhibition could have easily been a portrait of Klang as much as a portrait of the artist. In Urban Playground (1994), five children rollerblade underneath a flyover (Puah’s daughter is the model for the girl on the far right). Perspectives collide: the underside of the flyover and the dirt ground curve in subjective ocular perspective, mirroring the curvature of the eye, yet the shop houses, traffic light, and road signs on the left stand graphically, flattened in both perspective and color. The old and the new do not form a united front. Distortions abound elsewhere. Each child in the foreground stands independently of one another, caught in their own actions, their bodies out of proportion, torsos elongated, heads teetering precariously on necks that should be physically unable to support them. The central figure squints out of the painting: in this small pocket of Klang, his shirt reads, “OCEAN Pacific reaLLy BIG.” For Puah, Klang becomes the axis upon which the world arranges itself.

With Puah’s fondness for painting religious sites, ordinary people, and urban infrastructure, it is no surprise that his work has been read as typifying the genre of Malaysiana, a term as easily extended into bookstore category as souvenir marketing. Picture this: high-contrast photographs of exotic destinations and pristine beaches from Visit Malaysia tourism campaigns, nostalgic black-and-white films of old towns. Commonly associated keywords include tradition, community, memory. Although there is no doubt that Puah had a romantic attachment to Klang, he did not seem to indicate any interest in the project of picturing the nation (although, unusually, this image of the nation would be located not in the capital city of Kuala Lumpur but in Klang, the older port that gave rise to Kuala Lumpur and is now overshadowed by it). There is always a risk, in riffing on the typologies of “Malaysian” culture, of reinforcing rather than undermining the hegemony of the image of the nation-state. Yet, Puah always maintained a reflexive self-consciousness in his compositions, placing his works in irony and critique rather than reproduction.

His later engagement with the camera bites at the idea of documentary reality itself, as his project of sight expanded to include the question of photographic sight on canvas. The square and circle motifs of his early prints are refashioned as a viewfinder of a camera in his later paintings, such as Camera View of the Artist (1993), made asymmetric by the introduction of a color bar. Not accidentally, many of his paintings were made on square canvases in fealty to the perspectival possibilities of Platonic form. In the absence of the flat color fields that form the grounds of his earlier works, however, the viewfinder stands in as a signifier of a field: it is the condition, defining the space on which subjects are brought into relation. Puah’s subjects are mediated through the painter (the subject), the paint (the medium), and the lens (the mechanical-cultural apparatus). His paintings thus locate themselves on multiple timescales: the instant of the photograph, the duration of painting, and the time and place of Klang in the 1980s and ’90s. The viewfinder also makes apparent his compositional—or, more accurately, compositing—process, where he frequently took photographs to study his subjects before rendering them in paint. Puah’s paintings treat each brushstroke like a pixel, each line or shape a distinct color in stark contrast with the one adjacent to it. The picture emerges only when you step back. The image we are left with, like the idea of Malaysiana itself, is “virtual” in the dictionary definition of the term—that is, it is “almost or nearly as described, but not completely.”

KOK YEW PUAH, Festival Series I, 1992, acrylic on canvas, 162 × 162 cm.

Yet one wished to have seen a wider oeuvre of Puah’s in his retrospective. The exuberant tones of his figurative paintings, while highly technically accomplished, are made largely with the same compositional formula: figure(s) in the foreground in high contrast, a background skewed in perspective, and at times, the overlaying of a viewfinder. Two paintings suggest complications. The first, with no known title or year of creation, was given little context in the show. A bed of nails is pictured against a crumpled Chinese newspaper, reproduced down to each crease, each stain, and each character of its articles. The second is Festival Series I (1992), which breaks the convention of Puah’s figurative paintings. A surrealistic background of an empty green field is littered with rocks, its hues echoed in the sky and mountain on the horizon. In the foreground, six large joss sticks lay flat on the canvas, the open jaws of their decorative dragons pointed outward at viewers, as if an imposing fence. In the middle-ground stands a lonely Sarsi soda billboard in bright blue, per Puah’s signature use of high-contrast colors. In this picture within a picture, a woman stands with her mouth open, flanked by an F&N glass bottle and a glass of Sarsi nearly as tall as her. Her attempt to express desire is betrayed by the numbness of her eyes. Effervescent sprays erupt around and in front of her. Beyond reading into the painting as an easy metaphor of capitalist consumption, its darkness hints at the further possibilities and promiscuities of Puah’s sight. We would have had more insight, perhaps, if Puah had not passed away at the age of 51.

Puah’s sudden passing was at the curatorial heart of the exhibition. In the absence of the artist himself, the curators Beverly Yong and Rahel Joseph brought in a choir of interlocutors via videos scattered across the show to sketch an image of Puah. Included are his contemporaries, such as Anurendra Jegadeva and Sulaiman Esa; his family, such as his daughter Puah Sze Ning; and those who inhabit the larger world of his paintings, such as curator and artist Hoo Fan Chon. Together, these voices remember Puah not merely for his art but also for his warmth and generosity, reflected in the fact that he used to buy drinks for his artist friends at Studio 22 when they had late-night artist talks, and how he spoke to his young nephew as an adult. The gestures of his paintbrush and the gestures of his life suggest a man persistently empathetic and perceptive about the world around him. His art is the ethic of life.

"Kok Yew Puah: Portrait of a Malaysian Artist" is on view at Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, until April 3, 2022.