Resisting the Racist Blame Game

By HG Masters

MOMOKO SCHAFER, Prejudice is a Disease,

2020, lace and elastic hand stitched, worn on March 11, 2020, at South

Station, Boston. Photo by Mel Taing. Image via artist’s homepage.

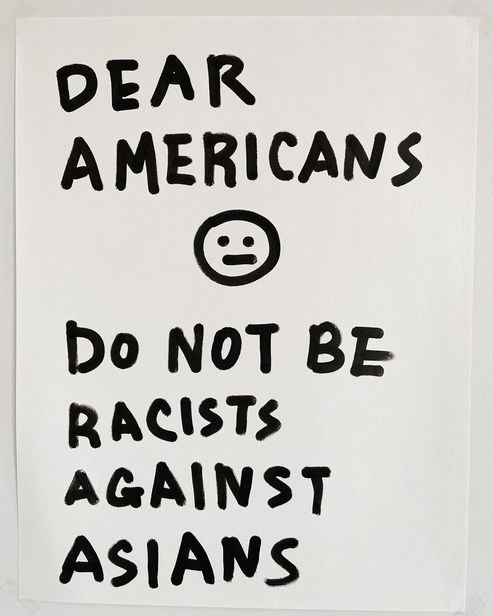

“Dear Americans :| Do Not Be Racists Against Asians” reads a drawing by the Brooklyn-based artist Taeyoon Choi which he posted on Instagram on April 2, after, he wrote, he was at the “grocery store and someone was aggressive to me for no reason.” In another post, he depicts someone in a public park yelling at him to “go back to where you came from.” Choi was born in San Mateo, California.

Incidents of racist abuse, violent attacks, and overt prejudice against people of Asian heritage—or those who appear so to others—have soared in the two months that Covid-19 went from being a disease with an initial epicenter in Wuhan to a global pandemic. The United States now has more than triple the number of confirmed cases than China, while Italy and Spain have been the most severely impacted countries in Europe to date. The virus knows no nationalities, but humans have been circulating hatred and bias right along with it. For many of Asian descent, it is a frightening and dangerous time. As the Brooklyn-based artist Bing Lee posted recently: “Fear pairing with anger is deadly.”

Taeyoon Choi is among many who have been chronicling racist incidents against Asians and Asian Americans. On March 8, he posted a sketch with the caption, “Somebody saw me and said ‘ching chang chong.’ Union Square Station, Today, 3.8.20.” He then offered several suggestions on “how to deal with racists.” “Be calm,” he writes, “don’t let the racist win.” Yet Choi acknowledged some hard truths about the prejudices that we all carry: “No one can escape racism because we live in a racist society.”

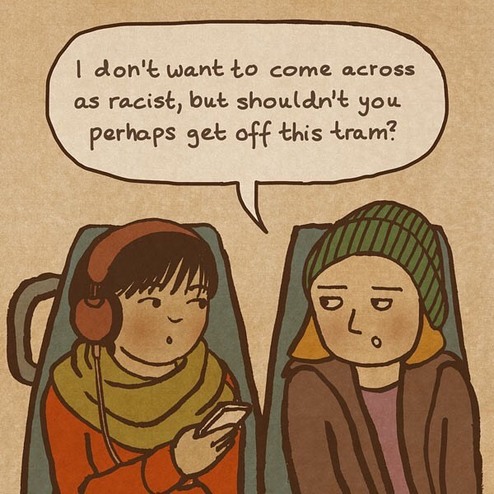

Since February, people have taken to online platforms to recount their stories using hashtags #Iamnotavirus, #jenesuispasunvirus, #nosoyunvirus, yet the discrimination has only intensified as acts of violence spread with the pandemic’s wave of fear. Based in New Zealand, the Swedish-Korean illustrator Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom has been raising issues about how children of Asian descent are being singled out for bullying or abuse. One of her drawings was inspired by the story of a Caucasian woman asking a 15-year-old Asian girl to get off a tram in Sweden.

Illustration by TAEYOON CHOI. Image via artist’s Instagram.

Illustration by LISA WOOL-RIM SJOBLOM. Image via artist’s Instagram.

The hostility and anxiety directed toward Asian people—particularly those wearing surgical masks, a phenomenon dubbed “maskophobia”—was what Japanese-American artist Momoko Schafer wanted to address when she donned a hand-stitched lace mask at Boston’s main transportation hub, South Station, on March 11. Her friend Mel Taing’s photos of her wearing the transparent face mask in the crowded public areas, subvert the expectations about Asians in masks and the menacing anonymity, or illness, that many have associated with them. As the artist reflected on Instagram: “Spending the majority of my life in the US as an Asian American, I have been conditioned to not do anything ‘too Asian’ to avoid making a spectacle of myself.” About her project, which she calls Prejudice is a Disease (2020), she wrote: “The objective was to highlight what the mask symbolizes today. Mask or no mask, my face invokes fear. Mask or no mask, my face can cause me to become the next target of hate.”

In the US, the long history of racism against Asians—epitomized by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first measure of its kind to exclude a single ethnic group from immigrating—was recently showcased in the exhibition “American Peril” at the Philadelphia City Hall. Mounted by collector Rob Buscher, an adjunct professor of Asian American studies at the University of Pennsylvania, the display of anti-Asian propaganda and racist artifacts from decades ago are eerily relevant today.

The dynamics of prejudice were captured with incredible alacrity by the Iranian-Canadian director Mostafa Keshvari, whose recently produced short film Corona (2020), features six people of various backgrounds, one of whom is a Chinese woman, trapped in an elevator, The film’s poster features the tagline, “Fear is a virus.”

Screengrab image from the trailer of MOSTAFA KESHVARI’s short film Corona, 2020, 63 min.

The spread of racial and ethnic hatred has been weaponized by politicians and their supporters around the world, including in Asia. US president Donald Trump has repeatedly referred to Covid-19 as “the Chinese virus” while his administration spars with China over a range of issues. But even in Hong Kong, the primary anti-government media outlets, which often align themselves with American neoconservative politicians on their anti-China stances, refer to the pandemic as the “Wuhan pneumonia” or the “Wuflu,” to cement the link between the devastation caused by the disease and the Chinese Communist Party. Meanwhile, discrimination against people from mainland China or Mandarin-speakers—a chronic local problem—remains as high as ever. More than 100 restaurants in the city, have, at one point, refused to serve diners from the region.

Elsewhere, Glasgow-based artist Frank To spoke out in a Glasglow Times article about “increasing racism” towards British people of Chinese origin due to the novel coronavirus outbreak, noting that his family’s restaurant had seen a decline in customers even while the outbreak was largely centered in China at the time. In Italy, street artist Laika’s paste-up mural in Rome’s Chinatown supports a local restaurant owner whose business has been severely affected. Wearing a white protective suit and mask, restauranteur Sonia is depicted saying: “There's an epidemic of ignorance going around . . . we must protect ourselves!!!”

HG Masters is the deputy editor and deputy publisher of ArtAsiaPacific.