Huang Yongyu, 1924–2023

By Cheryl Kwan

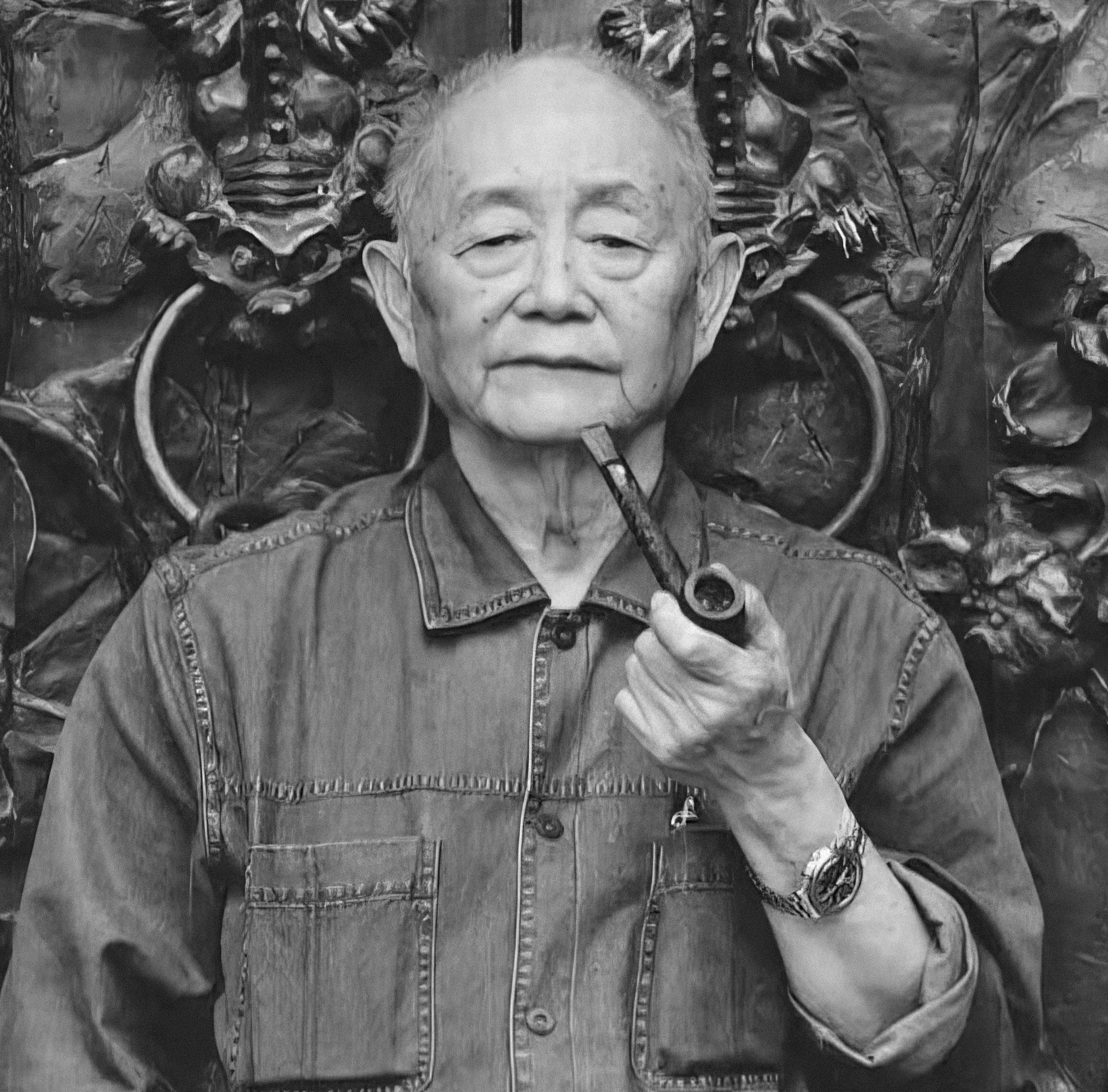

Portrait of HUANG YONGYU. Image from Wikicommons.

Chinese artist Huang Yongyu died at the age of 98 on June 13 after an unspecified illness. Hailed as a “national treasure,” Huang is known for his woodcut prints, ink paintings, as well as publication of his literature including essays and poetry. A self-taught artist with wild and unrestrained artistic style, he often incorporated animals as a main motif in his works.

Born in Hunan province in 1924, Huang dropped out of his secondary school and learned literature and art mostly by himself. He started travelling across China at the age of 13 and gained different artistic skills through working as a painter and woodcutter at various workshops and studios, before developing them into his practices of comic, oil paintings, ink paintings, sculptures, and craftmanship. To avoid rising political tensions in China in 1948, Huang left Shanghai with his wife Zhang Meixi for Hong Kong, where he gained local recognition after his solo exhibition at Fung Ping Shan Library in 1948. In Hong Kong, he also worked as an arts editor at the newspaper Tai Kung Po, where he befriended novelists such as Louis Cha and Leung Yu-sang, and at the journal The Great Wall Pictorial. In 1953, under the referee of his uncle, renowned writer Shen Congwen, Huang returned to mainland China and started working as a professor at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts, while continued exhibiting his works in Hong Kong as well as Taiwan. His itinerant life experiences contributed greatly to his freedom in artistic style and his often-wild depictions of animals and landscapes.

Wong once said that among the practices he enjoyed, he loved woodcut prints the most; literature comes second; painting comes the last and he mainly used the income from his paintings to support the first two creations. In 1956, he launched a woodcut print collection and created his signature series, Ashima (1956), a set of prints that accompany a collection of poems, featuring a traditional folktale from the Yi minority in Yunan, with the mythological figure modelled after women in the Sani tribe. In the early 1960s, he had developed a rather sophisticated style for his prints, which unlike his often-wild paintings with bold strokes, are more detail-oriented with skilful techniques. For example, one of his most famous prints at the time, Spring Tide (1961), meticulously illustrates with smooth lines a fisherman hunting in stormy waves a shark that flips over the surface of the ocean tides.

With a childlike innocence, Huang’s paintings of animals often highlight their distinctive features with an underlying sense of humor. He suffered greatly during the Cultural Revolution when his painting Owl (1973)—featuring the bird with one eye open and the other closed—was accused by then-CCP leader Jiang Qing of “subverting the Revolution and the Party.” After the Cultural Revolution, in 1980, he regained his reputation after painting a monkey for the postal stamp, in celebration of the Year of Monkey during the Lunar New Year. It became the first of China’s zodiac stamp series and Huang’s “monkey stamp” remains to be the most sought-after in China. Other ink paintings also feature animals such as Cat and Mouse (year unknown) in which the cat cunningly pushes a baby stroller with a mouse in it, or Crow (1980), in which the dark bird perches on a branch. In 2006, he donated World Peace (2006), a three-meter-long ink painting featuring cranes circling around the lotus, to the Chinese branch of the United Nations.

Throughout his career, Huang won numerous awards both within the country and internationally. In addition to winning a national award for his “Honorable Achievements in the Arts” in 2006, Huang is also the first Chinese artist to win the Olympic Art Prize, awarded by the International Olympic Committee in 2008.

In the past two decades, Huang held art exhibitions celebrating his 80th and 90th years of life. Up until his death, he was working on a centennial exhibition, scheduled to be held at Beijing’s National Art Museum of China next year. His works are collected by institutions including Hong Kong Museum of Art and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In accordance with Huang’s wishes, his family will not hold any mourning ceremonies. Huang is survived by his children and grandchildren.

Cheryl Kwan is an editorial intern at ArtAsiaPacific.