California Biennial Censors Satirical History Painting by Japanese-American Artist

By Monica Fernandez and The Editors

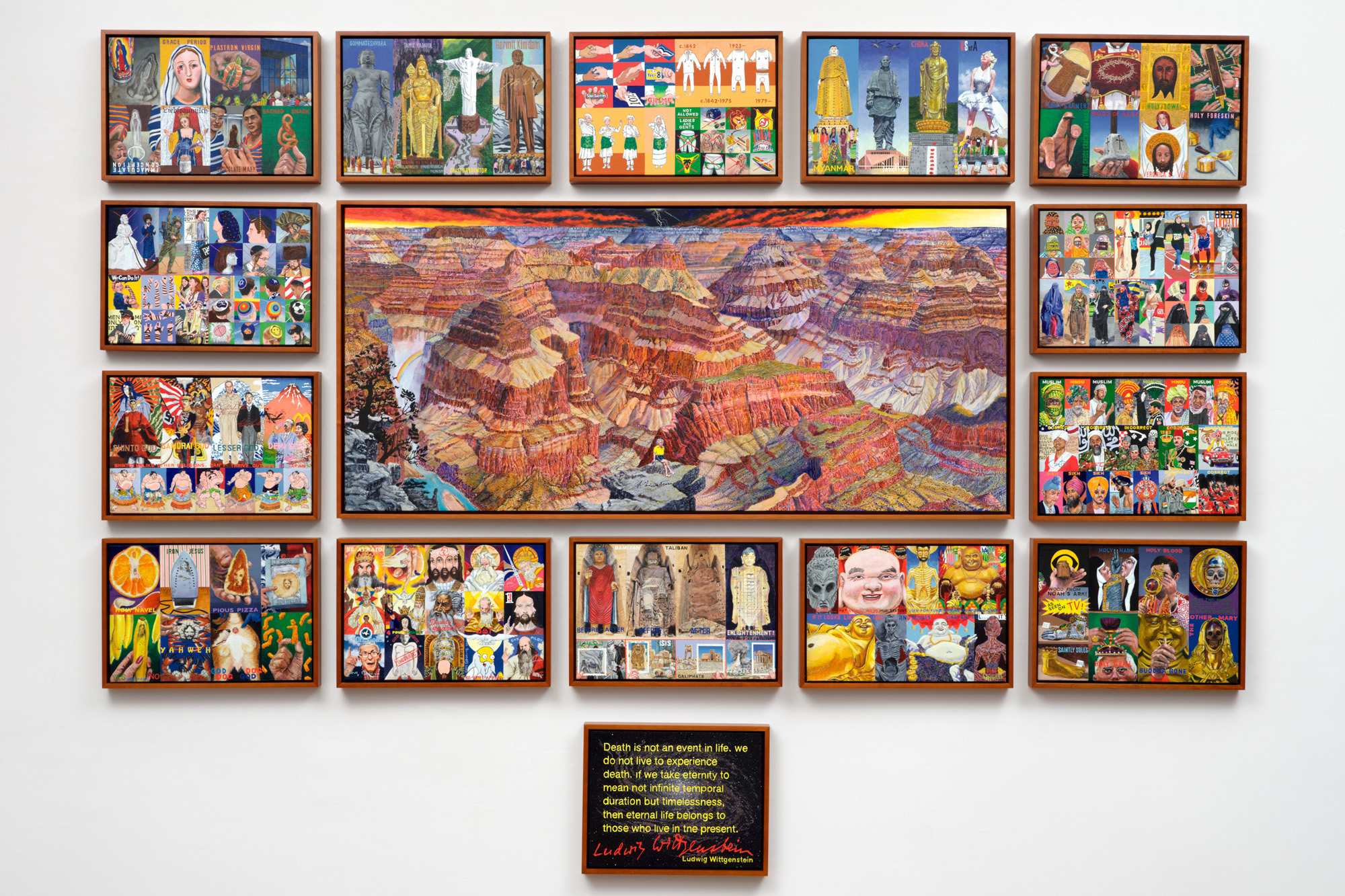

BEN SAKOGUCHI, Comparative Religions 101, 2014/2019, acrylic on canvas, 16 panels (28 × 41 cm / 28 × 36 cm / 61 × 135 cm), 130 cm x 230 cm. Courtesy the artist.

On October 8, the Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA), located in Costa Mesa, California, reopened its doors in a new building with a 24-hour kick-off, headlined by the return of the California Biennial. However, among the 20 artists invited to participate in the event, 84-year-old Pasadena-based artist Ben Sakoguchi was absent, owing to his invitation being withdrawn by the institution after it refused to display his 16-panel painting, Comparative Religions 101 (2014/2019), on the grounds that it contains representations of a swastika.

Sakoguchi released a detailed timeline of events on his website and again on his social media four days prior to the exhibition opening. In January, the Biennial’s curators Elizabeth Armstrong, Gilbert Vicario, and Essence Harden had invited him to participate in the California Biennial 2022, titled “Pacific Gold,” and on June 24 he was informed they had selected Comparative Religions 101. The painting was ready to be picked up when, on August 19, Sakoguchi first learned from the museum’s chief curator, Courtenay Finn, that the OCMA Education Department had raised concerns about its content. The museum sent him a set of questions about the themes in his painting and his process, even requesting audiovisual guides to aid in his explanation. Sakoguchi replied with extensive answers (which he posted on his website here). On September 12, before the OCMA had received his supplementary materials about the use of the swastika in world religions, the museum notified Sakoguchi that Comparative Religions 101 would no longer be shown at the Biennial, “because the museum will not show any work that depicts a swastika.”

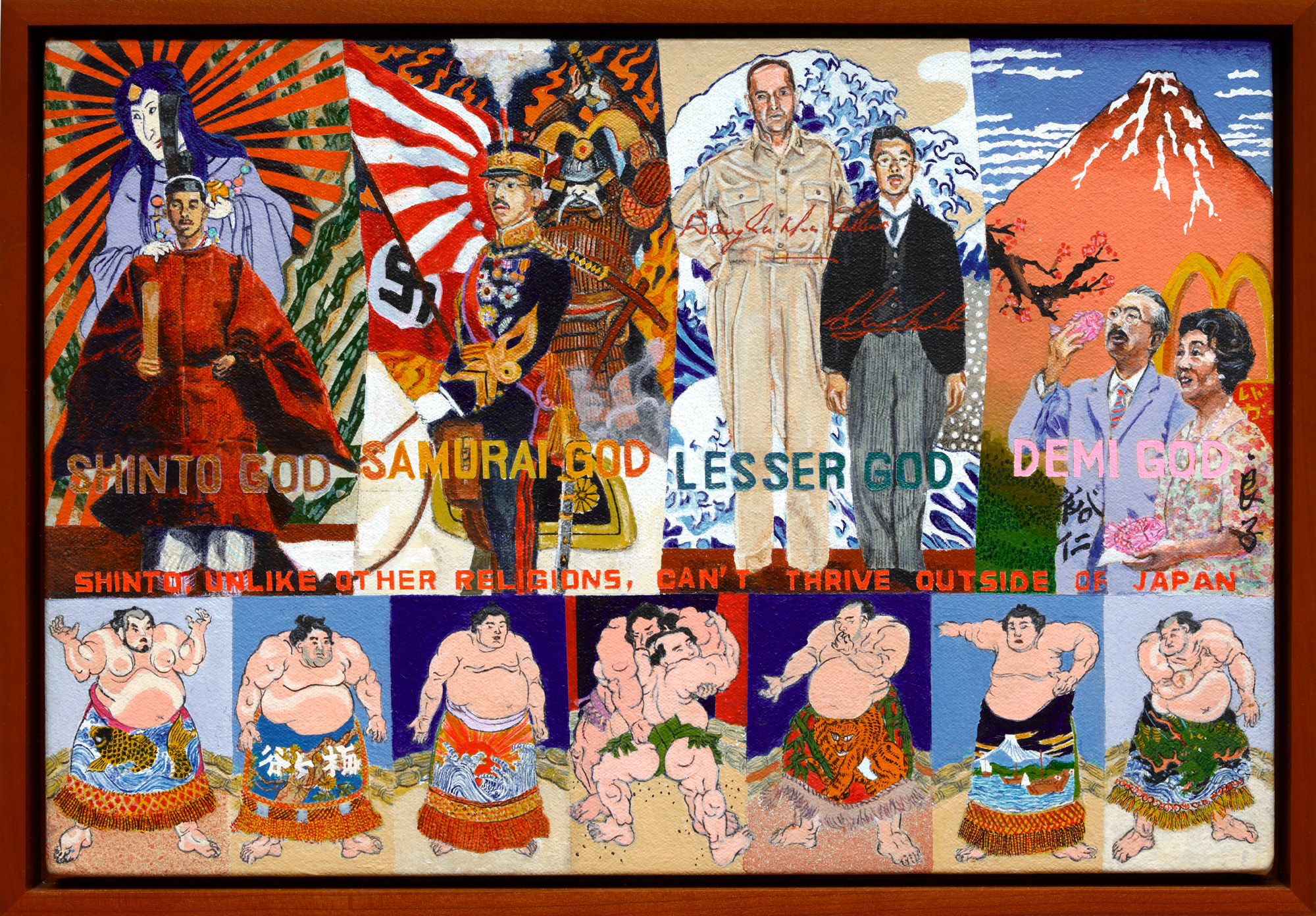

Detail of Comparative Religions 101, showing one of the usages of the

Nazi swastika alongside the depiction of Japanese wartime emperor

Hirohito who was allied with Hitler’s Third Reich.

When installed, the 16-part painting measures 1.3 by 2.3 meters; each panel is packed with references to different world religions and episodes from history, which Sakoguchi describes as “artifacts.” The swastika appears twice in the work—both times on a flag. The first instance is behind Emperor Hirohito, who ruled Japan during World War II, standing next to an armored figure with the words “Samurai God” emblazoned above. The second is on the flag flying next to the “Free India Legion,” the 950th Infantry Regiment composed of Indian students and prisoners of war who fought for Germany during the Second World War. The central panel is occupied by a depiction of famed scientist Albert Einstein dwarfed by the Grand Canyon, and is based on an actual photograph that served as an impetus for the work. In the canvases surrounding it, religious figures, representations of deities, and monuments are depicted together with pop icons and noted personalities from Marilyn Monroe to Rosie the Riveter, invoking the global clash of cultures and beliefs in the 20th century.

Though born in California, Sakoguchi himself experienced the racist policies of the United States government during World War II directed toward Japanese Americans. He and his family were detained in an Arizona detention camp along with as many as 17,000 other US citizens and residents of Japanese heritage—a subject he has dealt with in past bodies of work. In his response to one of the OCMA’s questions about his use of “xenophoboic, violent, and racist symbols, imagery, and language,” the artist replied: “I’ve been on the receiving end of xenophobia and racism for most of my existence, and have lived though a long period of time where continued violence, harm and negative stereotypes were widely tolerated and swept under the rug. I favor selectively shining a light on the offending symbols, imagery, and language, both past and present, as a reminder of our history and of how far we still have to go as a society . . and of how vigilant we need to be.”

In a last-ditch

effort, as reported by Hyperallergic, curators attempted to loan another of the artist’s works without his consent. After the artist’s representatives declined to assist them, the museum

reversed its decision and tried to persuade the artist to exhibit the painting. After being “selected” and then “rejected,” in the artist’s words, Sakoguchi stood by his decision not to participate in the Biennial.

The OCMA did not respond to an email inquiry by ArtAsiaPacific before publication.