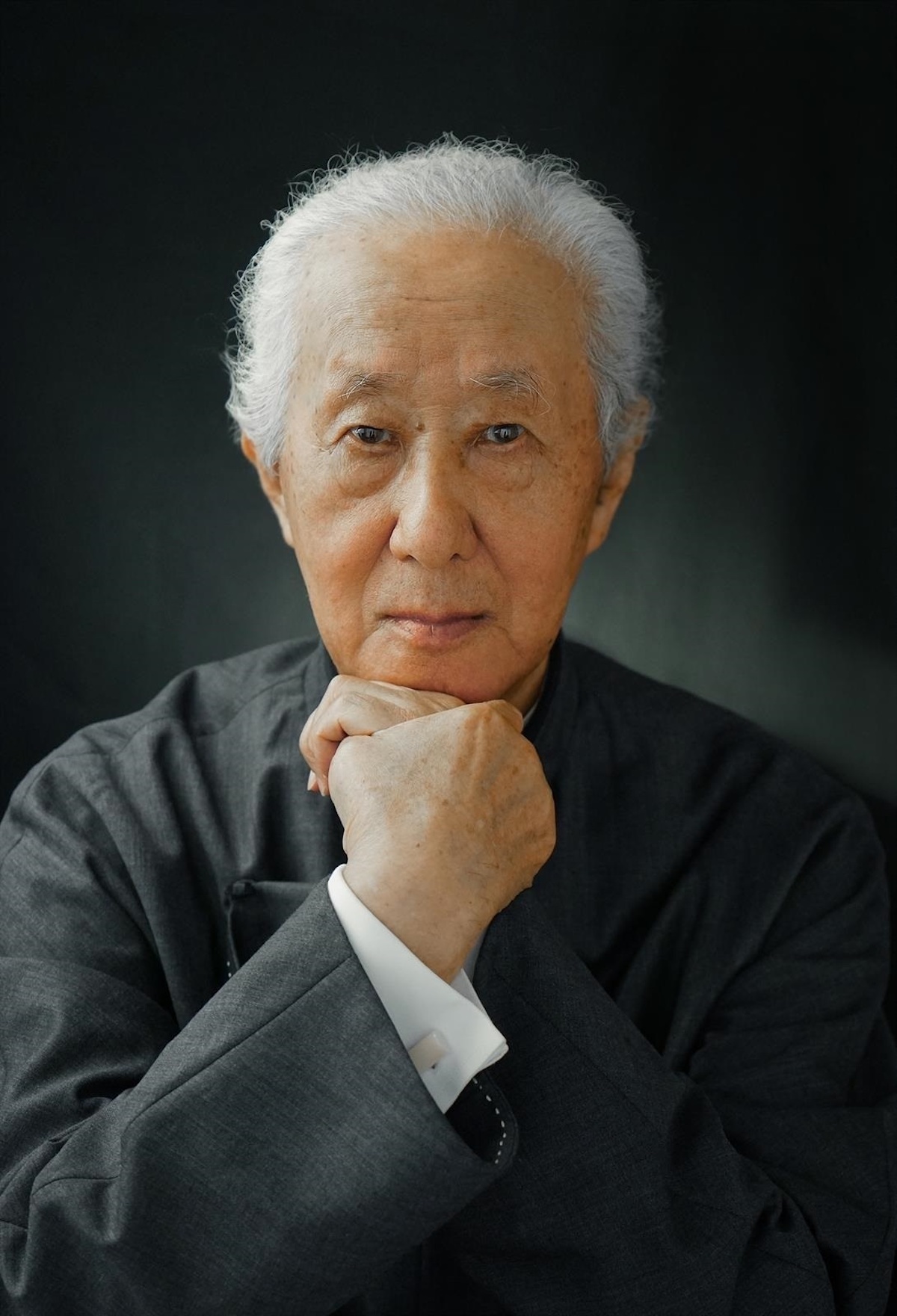

Arata Isozaki, 1931–2022

By Pamela Wong

Portrait of ARATA ISOZAKI. Image via Twitter.

Architect, urban planner, and theorist Arata Isozaki, named “the emperor of Japanese architecture” by his peer Tadao Ando, died of natural causes at his home in Okinawa on December 29. He was 91 years old. The news was confirmed by his longtime companion, the gallerist Misa Shin. As an architect whose style continuously evolved during his seven-decade career, the 2019 Pritzker Prize laureate is most well known for the postmodernist Tsukuba Center Building (1983); the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1987); Art Tower Mito (1990); and the massive Qatar National Convention Center (2011) in Doha.

Born in Oita, southwestern Japan, in 1931, Isozaki grew up in a wealthy family. His father was a businessman and a poet; his mother, who died in a car accident when he was in junior high school, came from a reputed family. At the age of 23, the aspiring designer graduated from the department of architecture at the University of Tokyo’s faculty of engineering in 1954. Then he began his career as an apprentice to the modernist Kenzo Tange, who was then working on the redevelopment project, “A Plan for Tokyo 1960.”

In the late 1950s in postwar Japan, a small group of young architects affiliated with Kenzo Tange proposed radical possibilities for the renewal of cities in an avant-garde manifesto, Metabolism 1960: The Proposals for New Urbanism. While Isozaki never publicly claimed to be a member of the movement, his first well-known proposal, The City in the Air (1962), resonates with the Metabolist ideal of a futuristic city of metamorphosis through continuously replaceable forms. In his never-realized plan, Isozaki proposed an architectural complex of recyclable mobile capsule units that extend toward the sky of Tokyo’s Shinjuku neighborhood. Unlike his Metabolist peers Kiyonori Kikutake and Kisho Kurokawa, who imagined the future of an industrial society, Isozaki was fascinated by the aesthetics of ruins and came up with the idea of “twilight gloom,” as seen in his 1968 project plan “Re-ruined Hiroshima,” which features distorted metal mega-structures standing in the aftermath of the nuclear bomb.

When Isozaki established his own architectural studio in 1963, Japan was still recovering from war and undergoing a material and spiritual rebuilding. He once explained: “In order to find the most appropriate way to solve these problems, I could not dwell upon a single style. Change became constant. Paradoxically, this came to be my own style.” His early brutalist designs such as Oita Prefectural Library (1966) heavily emphasized cubes and grids, a style that reached its heights when he was designing the Gunma Prefectural Museum of Modern Art (1974), which incorporates aluminum panels into 12-meter cuboid forms. He then shifted to exploring concrete vaults, as seen in the Kitakyushu Municipal Central Library (1974) and the Fujimi Country Club (1974). In the early 1980s, he moved to experiment with a neoclassical style in his controversial design of Tsukuba Center Building (1983). Referencing English painter Joseph Michael Gandy’s 1830 drawing of Bank of England as a Ruin, the complex comprises cubes and columns but is covered by reflective silvered tiles that erase the sense of the architectural body. From 1986 to 1990, he oversaw the design and construction of Art Tower Mito, which featured contorted geometric forms zigzagging toward the sky.

With more

than 100 completed buildings across the world, Isozaki considered himself as a

bridge between Asia and the societies of the West. His earliest overseas

projects began in the late 1980s with works such as the Grand Avenue building of the Museum of Contemporary Art (1987) in Los Angeles and Team Disney in Orlando (1991). The former is a sunken, red

sandstone-clad structure that poses a contrast with the glass and steel used in

the surrounding high-rise commercial buildings. For the latter, a colorful cone

stands in the middle of the four-story building blocks, introduced playfully

via an entrance hovered by an arch that appears to be Mickey Mouse’s ears. In the 2000s,

his master plans and buildings were realized in China, Saudi Arabia, Italy,

Germany, Spain, Vietnam, and other parts of the world. He continued to be closely associated with the construction of art galleries and museums, with the CAFA Art Museum in Beijing opening in 2008.

During his career, Isozaki published more than six books that discuss the history and philosophy of Japanese architecture as well as the urban development in Japan. He won numerous awards, including the RIBA Gold Medal in 1986 and the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2019. Misa Shin Gallery hosted an exhibition of Isozaki’s works, “Form and Spirit,” from November 2 through December 24, 2022.

Pamela Wong is an associate editor at ArtAsiaPacific.

%20x%20135(H)%20px-03Rc-72dpi%20(2).jpg)