When Archives Become Form

By HG Masters

Or, how to live in Ha Bik Chuen’s head

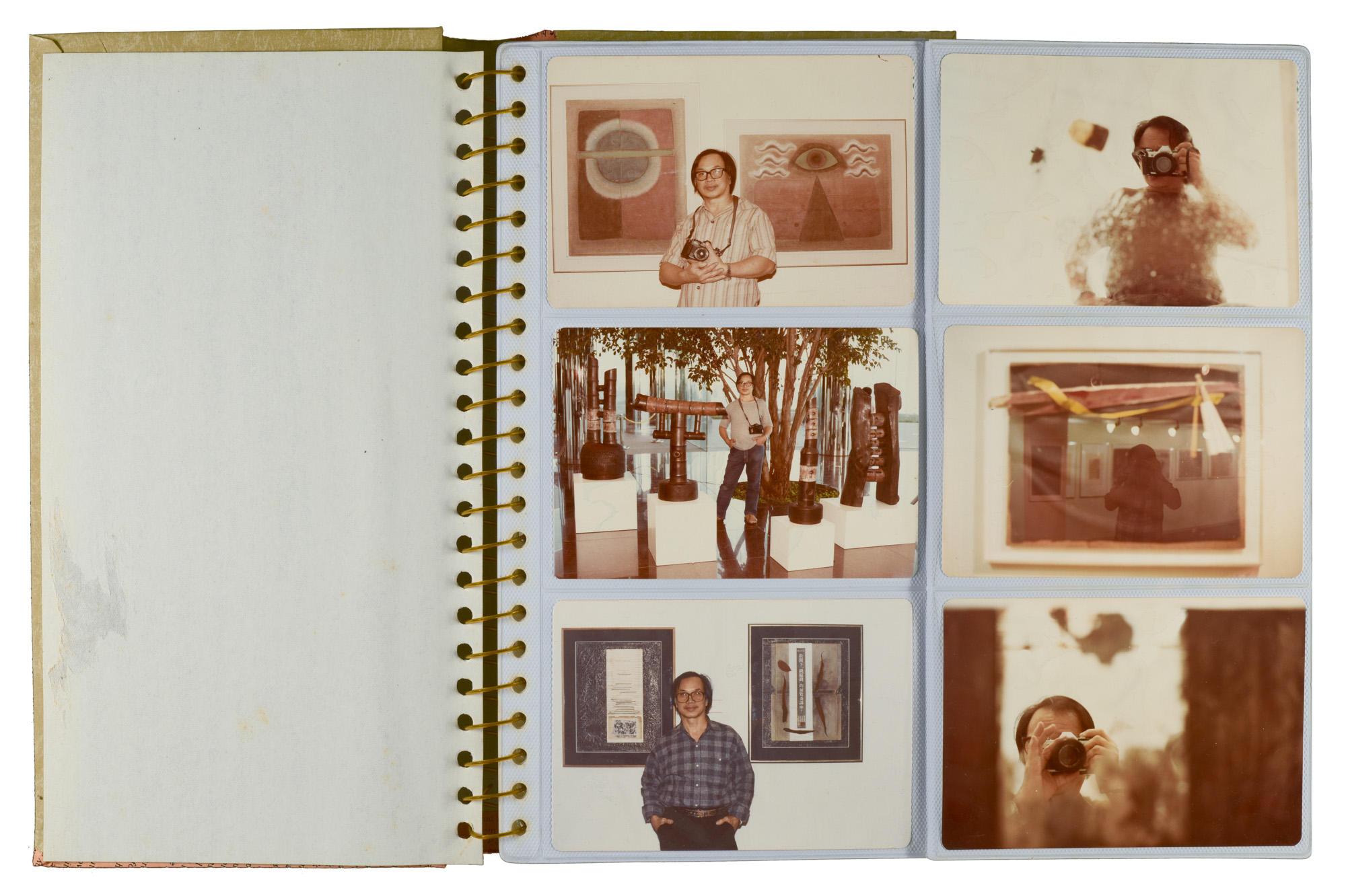

A page from the album "Pictures of Bik Chuen." The photos were selected and arranged by Ha Bik Chuen himself. Courtesy the Ha Bik Chuen family and Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong.

In April 2010, the digital art collective Pad.ma released a manifesto titled 10 Theses on the Archive. Its publication captured the anarcho-technological spirit undergirding the group’s construction of an open-source video-sharing platform, beginning with their exhortation to action, “1. Don’t Wait for the Archive,” and proposing alternatives to conventional understandings of historical material, such as “7. The Image is not just the Visible, the Text is not just the Sayable,” and “9. Archives are Governed by the Laws of Intellectual Propriety as Opposed to Property.” Pad.ma’s manifesto drew from—and distilled—a larger discourse around the function and place of archives at that moment, and coincided with the still- recent rise of information- and image-sharing services from Flickr to Pirate Bay, Facebook to Wikipedia. 10 Theses came at the crest of a conversation between artists and emerging institutions about the idea of what an archive could mean in regions with fragmented postcolonial histories scarred by cultural erasures, and as artists such as Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari (among many others) from Lebanon were seeking to re-examine the sense of history, and meaning, lost to time, and how it could be reassembled or reapprehended. Capping a decade of “archive fever,” during an unfolding series of conversations at events including Sharjah Art Foundation’s 2010 March Meeting and later at the Home Works 5 festival organized by Ashkal Alwan in Beirut, Pad.ma member Sebastian Lütgert went so far as to dub 2010 “the year of the archive.”

Like every research-based endeavor, “the year of the archive” has prolonged itself in duration and proliferated, migrated, and extended through numerous publications and exhibitions into new spheres of institutional practice. The exhibition “Portals, Stories, and Other Journeys,” curated by Michelle Wong and presented by Asia Art Archive (AAA) at Tai Kwun Contemporary, continued this conversation in the cultural context of Hong Kong and centered around the figure of artist Ha Bik Chuen (1925–2009). What Ha left behind in his “thinking studio” on the top floor of a tong lau (tenement) in Hong Kong’s To Kwa Wan neighborhood after he died was a trove of materials that, in their collective afterlife have become a resource of researchable materials sorted, boxed, preserved, and digitized by AAA. As the Ha Bik Chuen Archive, these documents are destined for Hong Kong’s art and educational institutions for future generations of scholars to access a primary record of Hong Kong’s art scene and material culture of the second half of the 20th century—most notably in the more than 2,500 exhibitions that Ha photographed between 1981 and 1998.

Yet as an exhibition “Portals” defied the conventions of a retrospective for an autonomous artist. Instead it portrayed how Ha’s creative life, seen through its archival remnants, has become a generative source for other artists—including Kwan Sheung Chi, Lam Wing Sze, Raqs Media Collective, and Walid Raad— and whose respective interests in Ha’s legacy brought them into a network of entangled conversations in the decade since his death. This approach echoes the spirit of Pad.ma’s third point from their manifesto—“The Direction of Archiving will be Outward, not Inward”— that archiving can be “to actually use and consume things, to keep them in, or bring them into, circulation . . . through imagination, not memory, and towards creation, not conservation.”

Installation view of A Restaurant in 1970s, c. 1970s, multimedia installation, dimensions variable, at "Portals, Stories, and Other Journeys," Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong, 2021. Photo by Kwan Sheung Chi. Courtesy Tai Kwun and Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong.

Wong fashioned “Portals” as a stage with ten “sets” that animated the archive in engaging but unorthodox ways. One corner of the exhibition was used to display large projected videos showing the interiors from a few of the more than 300 picture books filled with Ha’s collages of artworks, popular imagery, and design elements from disparate cultures and time periods. While the purpose or meaning of this visual thinking remains enigmatic—he never displayed them publicly— their projection into the exhibition space gave viewers the experience of entering into his eclectic visual universe, page after page. In a similarly immersive curatorial transformation, Ha’s bas-relief wall-sculpture of circles and squares, Construction (1967), from the collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Art, was restaged as a ceiling work, encircled by a panoramic photograph of a 1970s restaurant interior showing a similar design by Ha on its ceiling. From these objects, we feel the embeddedness of Ha’s creations in the material context of their time—even if this manner of equating an artwork with a ceiling decoration might violate the modernist sanctity of an art object.

“Portals” also paid tribute to how artists reveal aspects of one another’s practice. After Raad first discovered Ha’s collage practice in 2014 while rooting around in Ha’s materials, he also began to notice the occasional self-portrait among the documentation of many exhibitions. For his own installation, Untitled #79 (2020) Raad excavated Ha from images showing him in his various roles as an artist, a viewer of art, a documenter of exhibitions, and a travel photographer, and reprinted them as small stand-alone figures nestled among boxes from the archive. What Raad was interested in, as he describes to Wong in an email (reprinted in the booklet accompanying “Portals”), is how “[Ha’s] notion of art is in part tied to its reproduction and display.”

For Hong Kong’s own art history, Ha’s archive offers visuals to events both little known and fading from memory. One project he recorded was the “Hong Kong Reincarnated: New Lo Ting Archeological Find” exhibition organized by curator and critic Oscar Ho in 1997–98, following Hong Kong’s handover. The show was based on the myth that the city’s original inhabitants were descendants of a tribe of half-fish, half-human creatures called the Lo Ting. In “Portals,” a remade sculpture of the “humanoid mer-creature” from Ho’s exhibition was shown with images by Lo Yin Shan of Lantau Island, where the Lo Ting lived. The work revives memories of the discourse about Hong Kong’s postcolonial identity during a time of transition. Also recasting Hong Kong’s art history into the present, Kwan Sheung Chi’s contribution was a bronze sculpture titled Iron Horse—After Antonio Mak (2008), a sculpture of a horse divided into its front and rear halves by a metal barrier (known in Cantonese as an “iron horse”). The work refers to a 1982 sculpture by Antonio Mak in which a ladder divides a horse, and which disappeared after it was shown in a large group exhibition of Hong Kong artists at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila (an exhibition and voyage that Ha documented). Originally, Kwan created Iron Horse as a digital collage, with the barrier representing his blocked quest to find Mak’s original, but the object has since taken on additional resonances as a symbol of state power.

The affective register of Ha’s works—echoing Pad.ma’s thesis, “6. Historians have merely interpreted the Archive. The Point however is to Feel it.”—is explored in a five-channel, seven-minute video by Lam Wing Sze, Thinking Studio (2020). Lam interweaves her visits to places that Ha photographed in her non-narrative imagery, and also makes her own images with the materials that he used, such as leaves and seeds. Moody, romantic, sentimental even, the visual layering of Lam’s video is echoed in Raqs Media Collective’s installation of a sofa covered in a sheet of protective fabric screenprinted with a pattern based on an ink stain from Ha’s studio. A voice emitted from a directional speaker-fan offers mind-whirling reflections such as, “When a photograph is a photograph of a photograph of a photograph, meaning is possible only when promises begin to break.” The work, Monica Narula of Raqs explained in a video for AAA, references the archive as a “heuristic source” that leads to more connections rather than something that concretizes forms of knowledge.

Banu Cennetoğlu’s contribution to “Portals” was perhaps the furthest from Ha’s story in its references, as it relates to the artist’s own experience working with the diary of a Kurdish journalist and resistance fighter. The program of conversations that Cennetoğlu held— first with Wong and Özge Ersoy, the public programs lead at AAA, and then with fellow artist Jill Magid around her film-project about the Luis Barragan archive (The Proposal, 2018), and finally with Paul B. Preciado on Narcissister Organ Player (2017), a film about a neo-burlesque performance artist—centered the many issues artists face when working with other creative makers and their materials, and the responsibilities that artists might have as custodians, caretakers, or provocateurs.

The reality of creative life, as “Portals” revealed, is that it seeks out, devours, and metabolizes the energies of others. Modernist exhibition practices still operate on principles of extraction (showing the best or most valuable works) and preservation (of materials and legacy), and tend to isolate artists from one another and from their contexts to emphasize the uniqueness of their vision, rather than their connectedness. But this overlooks the free-flowing borders between art and life, studio and world, friends and rivals. Thinking of an artist’s retrospective as an unbounded archival exhibition, for example, and as a site to understand an artist’s practice from the inside outward, offers more vital prospects for keeping the stories and ways of the past alive and close to us into the future.

.jpg)