Tsai Ming-Liang: Bound By Nothing

By Frances James

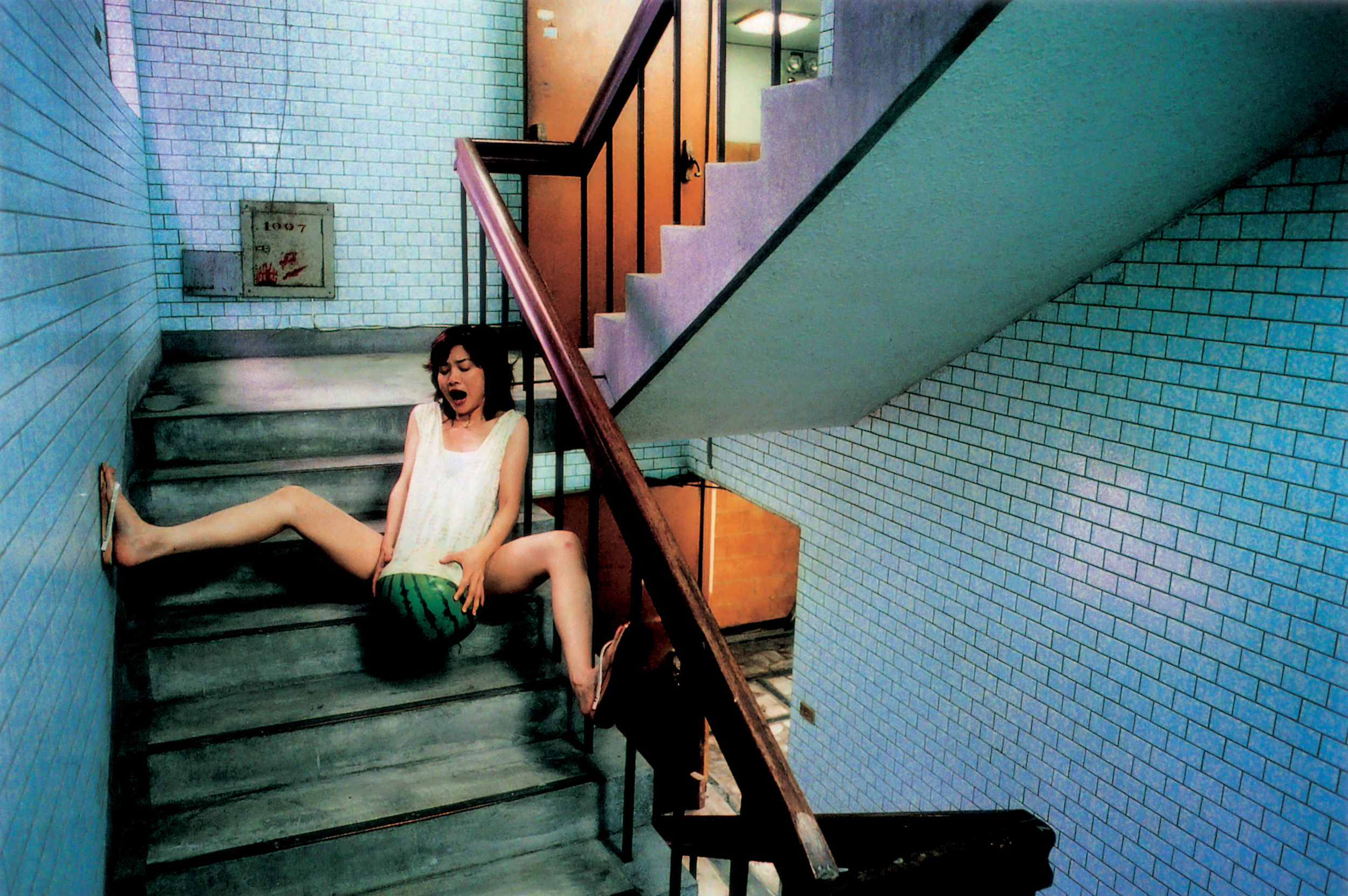

TSAI MING-LIANG, The Wayward Cloud, 2005, 112 min. Photo by William Laxton. Courtesy Homegreen Films, Taipei City.

We eat, excrete, sleep, and get up;

This is our world.

All we have to do after that,

Is to die.

Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481)

Near an open-air market in a neighborhood of Kuching, Malaysia, an abandoned building with a faded blue facade and a large sign that reads “Cathay” is being steadily overtaken by weeds. Eventually, like all things, it will be consigned to oblivion. Once teeming with people rushing to see the latest films from Hong Kong, Hollywood, Japan, and India, the Cathay is now a vestige of a golden age of cinema in a city once home to a dozen stand-alone movie theaters. As a young boy, Tsai Ming-liang was taken to these hallowed spaces “twice a day, every day” by his grandparents, fomenting an early devotion to cinema.

Tsai left his hometown of Kuching for Taipei in 1977 to enroll in the film and drama program at the Chinese Culture University where, at the age of 20, he discovered the plays of Shakespeare, Ibsen, and Brecht, and the films of Truffaut, Bresson, Antonioni, and Fassbinder. These influential figures would go on to impact his approach to filmmaking and bring him to the realization that cinema is capable of revealing “something of the real world.” In Taiwan, realistic depictions of everyday life appeared on screen in the early 1980s when filmmakers including Edward Yang, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Ko I-chen, and Wu Nien-jen emerged as part of the Taiwan New Wave. Auteurs of this period believed in cinema as a “self-reflective art form” and provided the space for an alternative cinema to exist in a landscape dominated by commercially driven state-sponsored studio films.

After graduating, Tsai wrote and directed his own theater productions, including The Wardrobe in the Room (1983), a one-man play that he performed himself about a city dweller who shuts himself off from society, a society in the midst of rapid socioeconomic transformation (beginning after the death of Chiang Kai-shek in 1975). 1987 saw the end of four decades of martial law—which coincided with the beginning of Tsai’s career as a producer, screenwriter, and director for television—and in 1991 he made a small-screen film about a teenage bully played by Lee Kang-sheng, a high school graduate with no acting experience that he spotted lingering outside a games arcade. They have worked together ever since and, with the exception of Chishu Ryu (who appeared in all but two films directed by Yasujiro Ozu), Tsai and Lee’s longtime collaboration is unprecedented. To date, Lee has starred in all 11 feature films directed by Tsai, including his portrayal of a taciturn dropout in his debut feature Rebels of the Neon God (1992); the Golden Lion best film Vive L’amour (1994); his ode to cinema, Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003); and most recently, Days (2020), in which Lee plays a version of himself seeking treatment for chronic back pain.

TSAI MING-LIANG, Afternoon, 2015, 137 min. Photo by Chen Chien-Chung. Courtesy Homegreen Films, Taipei City.

An early interest in urban alienation continues to course through Tsai’s work, with the restless, weary, lonely souls filling his frames, many of whom fail to connect, and who, despite living with one another, are also very much alone. So much so, that his characters are often seen eating, cleaning, masturbating, urinating, walking, or simply staring vacantly into space. And while he is recognized for his use of long takes, static camera, and little to no dialogue, the inclusion of elaborate musical numbers in films such as The Wayward Cloud (2005)—in which Lee acts as a porn star, appearing in one scene dressed as a giant penis; and in The Hole (1998) where Lee and Yang Kuei-mei’s characters break into ecstatic song and dance in the corridor of a flooded apartment complex—epitomize the uncategorizable nature of his work. Ever since the release of 2013’s Stray Dogs (his self-proclaimed swan song), Tsai has freed himself from the industrial processes of feature filmmaking and has gone on to explore various modes of production, distribution, and exhibition, showcasing his work in galleries, cinemas, and museum spaces. And over the last decade his work has become increasingly meditative, challenging the “endlessly impatient hearts” of spectators while turning his lens toward the ever-changing, aging body of his muse and friend, Lee Kang-sheng.

Tsai, who is a practicing Buddhist, appears, in the flesh, almost monk-like, with his clean-shaven head, long earlobes, thick eyebrows, and piercing brown eyes. We met one April morning in Hong Kong (a city he adores) in a nondescript hotel room, where people are always, and never, at home. With his producer working quietly away in the background, and the mass of people going about their daily lives in the streets below, we discussed his views on the film industry, his experiences with anxiety, and the considered approach he takes to depicting sex on screen.

Comparing cinema and painting, Walter Benjamin wrote that “the painting invites the spectator to contemplation; before it the spectator can abandon himself to his associations. Before the movie frame he cannot do so.” I’m interested to know more about how you approach filmmaking from the perspective of painting and how you blur the line between cinema and visual art.

Cinema is commodified and treated as entertainment, which is why the same concepts are used over and over and the same types of films are made, just like canned food. But cinema is a unique artistic medium with a great creative potential. In my own work I de-emphasize plot. It’s what the images express that’s important. There are a lot of long takes in my films, and I don’t cut or edit scenes to drive the plot forward. I think the film industry limits the development of cinema as an art form, in part, because of all the requirements: screenplays, technical information, easily digestible material etcetera. Consciously or not, I’ve strayed from all that. For example, in the Walker series (2012– ) I’ve cut out all narrative elements. I’ve gradually become more like a painter, whose creative freedom I envy. I try to use my camera to paint—with elements of light, composition, and a sense of time slowly passing.

TSAI MING-LIANG, The Wayward Cloud, 2005, 112 min. Photo by William Laxton. Courtesy Homegreen Films, Taipei City.

Speaking of the Walker series, the latest installment, Abiding Nowhere (2024), has just had its Hong Kong premiere, along with your acclaimed play The Monk From Tang Dynasty (2014). You once described your interest in the seventh-century monk Xuanzang as an obsession. What initially drew you to him and his approach to the world, and how did this obsession find its way into your work?

When I began reading Buddhist texts in my thirties I became especially interested in Xuanzang, a monk who walked alone in the desert. Years later I’d grown tired of repeating myself after eight feature films, and the National Theater in Taiwan invited me to direct a play [Only You, 2011]. I wanted Lee Kang-sheng to act as himself, as my father, and as Xuanzang at the same time, so during rehearsals I made him walk very slowly. It took him 17 minutes to move across the stage, and I was deeply moved by his performance. But once a play is over, it no longer exists, so I decided to make a film about Lee walking: no story, just a conceptual approach inspired by Xuanzang. I received funding in 2012 and began the Walker series. Two years later Art Brussels and Vienna Festival invited me to produce a play and I decided Lee should act as Xuanzang in The Monk From Tang Dynasty. So it’s gone on this journey from the stage to the screen and back to the stage again.

TSAI MING-LIANG, The Monk From Tang Dynasty, 2024, theater performance at Tai Kwun, Hong Kong, 120 min. Photo by Claude Wang. Courtesy Homegreen Films, Taipei City.

TSAI MING-LIANG, The River, 1997, 115 min. Courtesy the artist.

Your move from the city to the mountains near Taipei seems to have coincided with the more minimalist, meditative direction you’ve taken in your work over the last decade or so. How has your outlook on life and your sense of time altered since you relocated there?

During the production of Stray Dogs I became very weak and began suffering from anxiety. Whenever I sat down I had to grab a chair. I was afraid of losing my balance, afraid of falling. It turned out to be some kind of panic disorder. I got better after moving to the mountains as I’m surrounded by trees; it’s isolated and very quiet. The move also coincided with my becoming less interested in narrative filmmaking. I didn’t have any concepts for screenplays in mind, and even though I didn’t want to shoot anything the environment compelled me to look more closely at my surroundings, which were covered in ruins. Even my house was a ruin. I told Lee that we could make something, which we did, experimenting with virtual reality. Thinking back on why I got this strange illness, why I would panic for no reason, I think it’s because I had been exhausted for so long. But after I moved to the mountains, everything slowed down. There’s no rush to make anything now.

In his 1862 essay Walking, the American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau wrote about the origins of the word saunter which possibly derives from sans terre in French, meaning “without land” or as Thoreau put it, “having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere.” I’m interested in what this idea of home means to you and how it has shaped your work, particularly in relation to your focus on themes like alienation.

What you said about Thoreau resembles ideas in Buddhism. There is an important scripture in Buddhism called the Diamond Sutra, part of which goes: “bound by nothing in order to explore from within”—meaning that the heart doesn’t abide anywhere; it is always roaming, without a place of belonging. I was born in a small city in Malaysia and grew up in the late 1950s and early ‘60s. Back then, things were slower. It was an era that felt like it had just woken up: the war had ended and there was a period of recovery. There wasn’t a big gap between rich and poor. There was hope for the future, and technology wasn’t racing forward like it is now. Without televisions most people went to the cinema or listened to the same pop songs on the radio. I lived with my grandparents who let me do my own thing. That was their philosophy. We only came together at dinner or when we went to see movies together. I enjoyed a lot of freedom. At some point, I was brought back home by my father who was very controlling. I often felt like running away. Sometimes, I stayed overnight at my friend’s house and wouldn’t return. Once I reached adulthood, I realized I still had this personality trait. I need to feel free in order to express myself. But I have felt a sense of alienation from home. I don’t know which place is my true home and I have no sense of belonging anywhere. People have asked me if Taiwan is my home. I didn’t think that was the case, and it was only when I got older and moved to the mountains that I felt like I had settled down. There’s a sense of going back to nature in the mountains. So it wasn’t until I was in my sixties that I felt settled down at heart. But I’m always searching for greater freedom in my creative work.

TSAI MING-LIANG, Stray Dogs, 2013, 138 min. Photo by William Laxton. Courtesy Homegreen Films, Taipei City.

Closely related to alienation are other recurring themes found in your films, such as longing and desire. What might ordinarily be considered shocking, disturbing, or perverse can conversely be rendered profoundly moving in your depictions of sex—for instance, the scene in which a father inadvertently masturbates his own son in a dark sauna room in The River (1997) or the climactic ending of The Wayward Cloud (2005). What is the process in which you create these types of scenarios? How do you get your actors to trust you to the degree that they do and how do you play with audience’s expectations?

I have a special relationship with my actors. Whether I’m shooting body parts or sex scenes they know I’m not going to use the material to grab people’s attention because I don’t make decisions like a commercial director. Looking back at The Wayward Cloud [the restored version of which was screened in the Hong Kong International Film Festival this year], I’m grateful to my actors for their trust, otherwise I couldn’t have made it, especially as Asian actors and actresses tend to be protective of their bodies. But for some reason they are willing to make sacrifices in my films. On the other hand, I think my films stem from life, and you can’t exclude sex. Eating, drinking, going to the toilet, and having sex are all part of living. In order to convey a sense of authenticity I need to include scenes of going to the toilet or having sex in my films. With some life experience we all know that sex isn’t always good. There can be a lot of probing, testing, anxiety, and all kinds of emotions involved. I try to present that reality. The sex scenes in my films are different from those in commercial films which tend to beautify the whole thing in order to fill the viewers with fantasies. I only want to present the reality.

In the documentary Afternoon (2015) you openly discussed your fears and anxieties, especially concerning death and illness. You even suggested that you might be coming to the end of your life and described your relationship with Lee Kang-sheng as “beautiful” but “impermanent.” Are your films perhaps a way of creating something indelible?

In my relationship with Lee Kang-sheng there’s no sense of dominance. We’re like two sides of the same coin. At first I didn’t think he would be able to act, but I became convinced by his style and his slow tempo. I realized that I needed to subvert the rules and escape any ideas of what acting is or what films are. He inspired me, and his acting style allowed me to see that the form could be natural and beautiful. When I was making my fifth film, What Time Is It There? (2001), I suddenly realized that I would never move the camera away from him. I didn’t have these kinds of thoughts before. I express my thoughts and reflections on life through his body. You see, I rarely talk with Lee Kang-sheng. We live close to each other but we seldom talk. And when we do it’s only about trivial matters. Even during the process of creative work we barely talk. That’s why [the documentary] Afternoon exists. I was afraid that we would have nothing to talk about, so I asked a few friends to sit behind the camera and act as our audience. That way we couldn’t escape. We were forced to sit and talk. We talked for two hours and it eventually became a film. Films have the mysterious ability to freeze time. Even if a person is no longer alive, their image lives on.

TSAI MING-LIANG, Days, 2020, 127 min. Courtesy Homegreen Films, Taipei City.

Frances James is a writer and filmmaker based in Hong Kong.