Simon Fujiwara: All the World’s a Cartoon

By Frances Arnold

Who’s in the Clouds? (detail), 2021, two-part collage of inkjet prints and colored paper, 68 × 95.5 cm each. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

“How can I make art when all the world is a conceptual artwork? What do you do then?” Simon Fujiwara is known for his complex and multilayered works spanning everything from the rebranding of a woman whose career was destroyed after her private photos were circulated in her workplace, to the origins of commercial culture via the last queen of France. His most recent project is a cartoon bear named Who, with an appetite for images and a quest for identity. Who is an extrapolation from an approach that runs throughout the artist’s body of work. An inveterate storyteller, Fujiwara exposes and unpicks issues of identity through near forensic investigations into images including literal likenesses, public personae, ideology, and myth.

The British-Japanese artist’s childhood was spent in St Ives, in southwest England. “I suppose one of the good things about growing up there was that it was so boring,” Fujiwara reflected. “It was very much a monoculture, very remote—and, of course, before the internet, so I spent a lot of time daydreaming and waiting for magazines I’d ordered on subscription to arrive. I think that’s why my interest in images started—because I was so starved of them.” Despite St Ives’ significant art credentials—famed for its superlative light, it has been a mecca for artists since the late 19th century, its legacy cemented by the launch of mega museum-brand Tate’s outpost there in 1993—it wasn’t the town’s offerings that inspired the teenage Fujiwara. “I mean, what’s a kid going to do with lots of abstract paintings and Barbara Hepworth sculptures?” he said. Rather, he looked to the YBAs, or Young British Artists. Widely dubbed the enfants terribles of the art world when they emerged in London in the 1990s, the YBAs were, for a time, just as likely to appear in British tabloids for stumbling out of nightclubs as they were for their art. It was in newspapers that Fujiwara first encountered these scene-shaking artists, with one in particular igniting his sense of rebellion. “It was Tracey Emin that I really related to,” he recalled. “It wasn’t just that she was also from a small seaside town [Margate]; the idea of exhibiting your bed was so amazing to me and such an affront to society, structure, and everything else that I also didn't really relate to.”

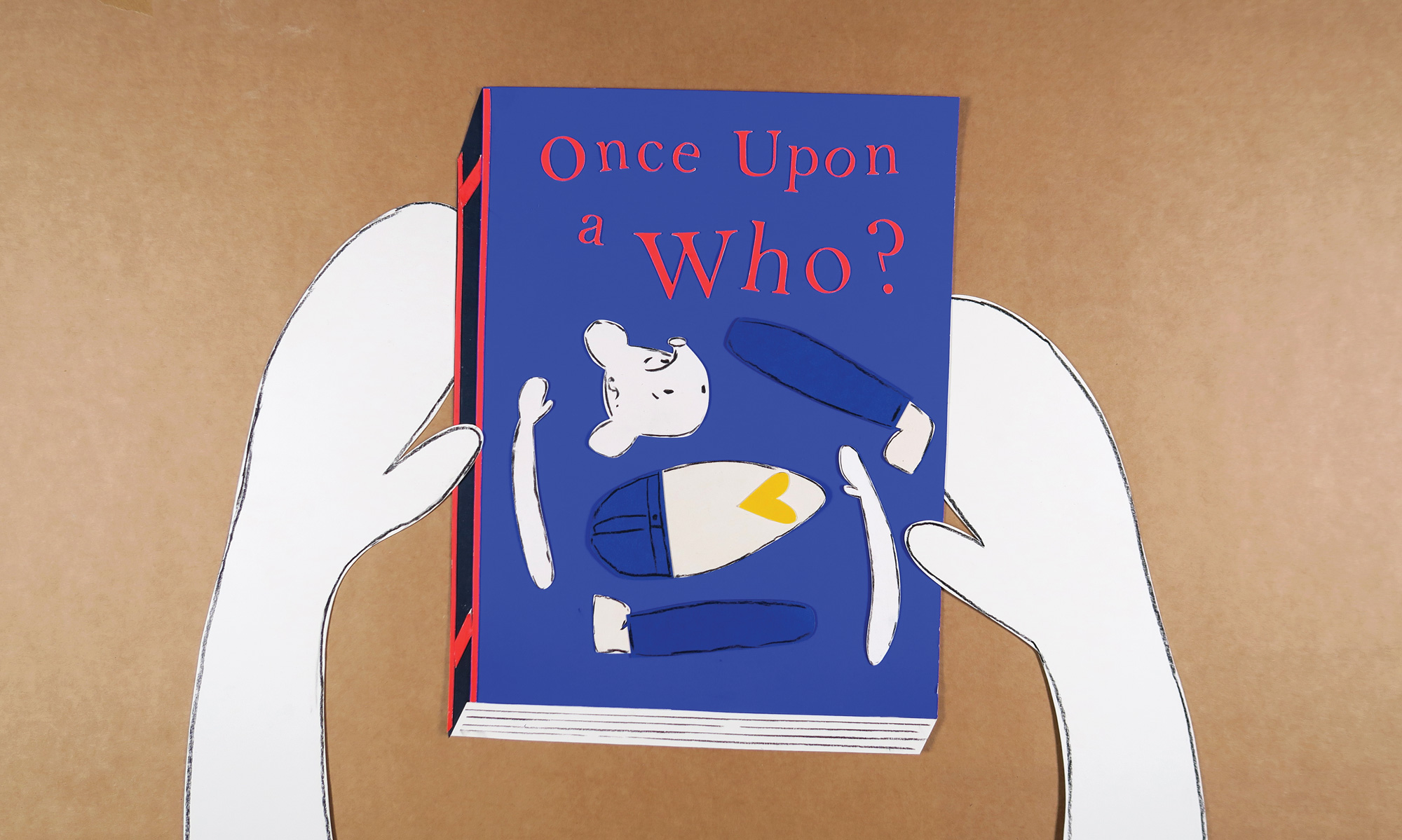

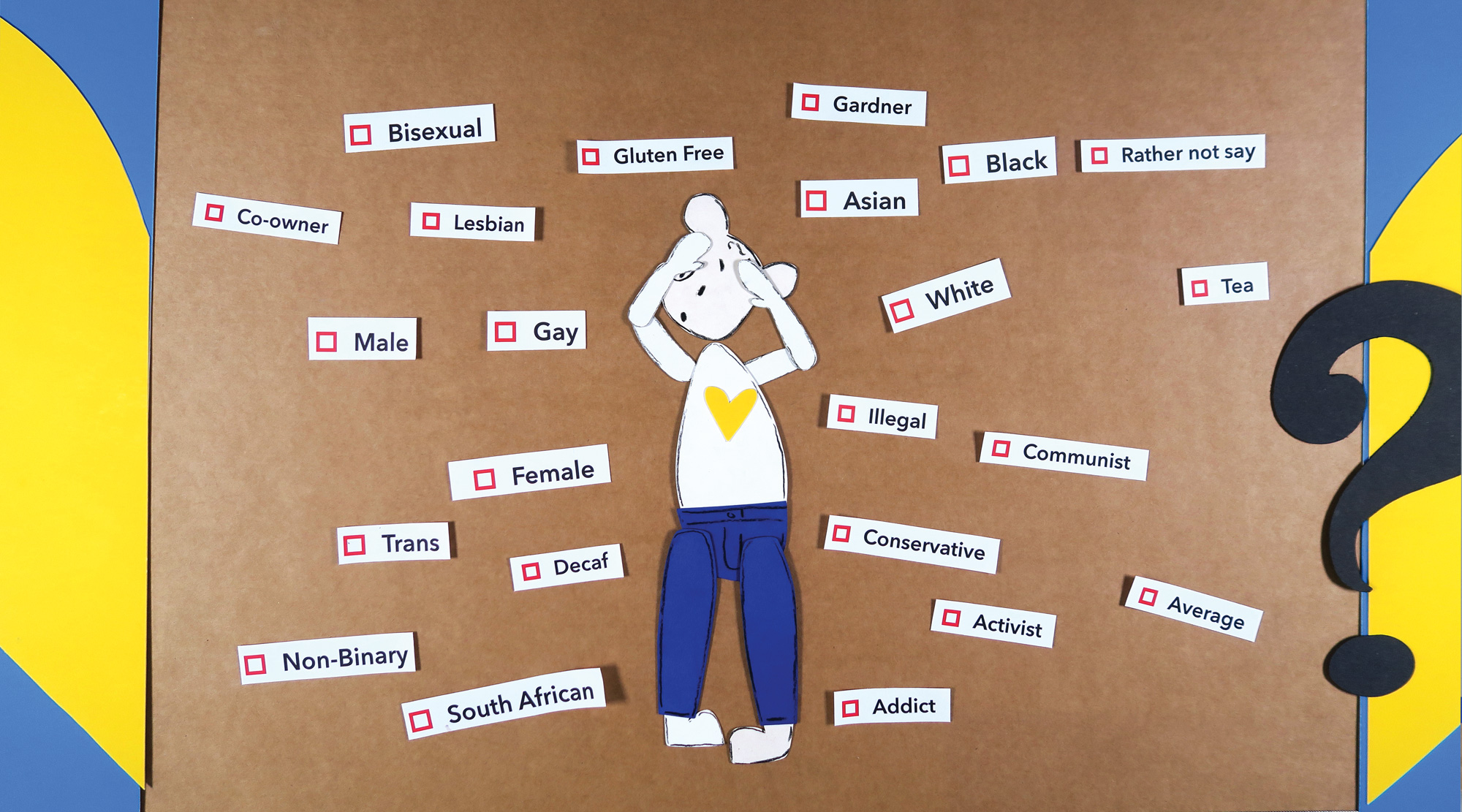

Once Upon a Who?, 2021, stills from stop-motion animation with installation: 4 min 48 sec, overall dimensions approximately 4 × 5 m. Courtesy the artist; Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv/Brussels; and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Once Upon a Who?, 2021, stills from stop-motion animation with installation: 4 min 48 sec, overall dimensions approximately 4 × 5 m. Courtesy the artist; Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv/Brussels; and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Once Upon a Who?, 2021, stills from stop-motion animation with installation: 4 min 48 sec, overall dimensions approximately 4 × 5 m. Courtesy the artist; Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv/Brussels; and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

After leaving St Ives to move to Japan and then to London with his family, Fujiwara went on to study architecture at England’s University of Cambridge, secure in the conviction that although art would be his life, a grounding in a different subject matter would not be a bad thing. “I’ve used [my architectural training] a lot in my work,” he said. “The projects are constructed in a very three-dimensional way, philosophically and theoretically. I think about the user—the audience—and about how everything occupies a space, how you see things in sequence.”

In 2006, Fujiwara moved to Germany, initially dividing his time between Berlin and Frankfurt where he studied fine art at the Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste. There, he developed a series of quasi-autobiographical performative works, presented as narrated tours through imagined architectures. They include The Incest Museum (2007– ), an absurdist mashup of ethnography and eroticism comprising a painting by his father, a slideshow, publication, and artifacts from northern Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, which is dubbed the Cradle of Mankind for its paleoanthropological importance. The multipart work revolves around the premise that for species survival, early man must have engaged in incest. Fujiwara traveled to Tanzania, following in the footsteps of his father whose photograph from the same journey almost 40 years prior features alongside newspaper cuttings reporting the 1964 announcement of ancient human Homo habilis’ discovery. Further blurring shared and personal histories, the architecture of Fujiwara’s proposed museum is directly inspired by a three-globed goldfish bowl, designed by his architect father.

Detailed installation view of Welcome to the Hotel Munber, 2008-10, mixed-media installation, dimensions variable, at "Art and Porn," ARoS, Aarhus, 2019. Photo by Anders Sune Berg. Courtesy Collezione Prada.

Similarly, Welcome to the Hotel Munber (2008–10) weaves Fujiwara’s family history into an elaborate fictional narrative, set inside a reconstruction of the bar at the hotel his family once owned in Catalonia, Spain. The work is a homoerotic retelling of his parents’ experiences during the dictatorship of Spanish general Francisco Franco. Based around an erotic novel Fujiwara attempted to write, it addresses sexual oppression during the fascist regime through the desires of its protagonist—the artist’s father—and its physical setting, which is hypereroticized through phallic and suggestive objects. This signature combination of storytelling and conjuring places was in part a reaction to his art-school peers who, Fujiwara said, “Weren’t really accepting of me as an artist at first, because I’d studied architecture. It was as if there was some kind of purity to this identity of an artist, a kind of pedigree.” That his performances won over his fellow students was the catalyst for a major theme that runs through Fujiwara’s practice: engineering identity. “They were, like, it’s so personal, so weird, so specific, or so collaged. I thought, ‘This is interesting: I have the power to really play with how people see me, what my identity is.’”

Fujiwara’s semi-autobiographical approach continued after his graduation from art school in Frankfurt. Created for his “Since 1982” exhibition at Tate St Ives in 2012, the video Rehearsal for a Reunion (with the Father of Pottery) (2011) revolves around a drama that he wrote about his reunion with his “distanced” Japanese father, during which the pair made a ceramic tea set. Over the course of the work, Fujiwara and a hired actor playing his father discuss the script, set “somewhere between England and Japan,” and the symbolism of the replica teacups fashioned after those by the Hong Kong-born “Father of British Pottery,” Bernard Leach (1887–1979), whose own life straddled East and West, and whose East-Asia-inspired ceramics Fujiwara recalls visiting in the St Ives museum dedicated to his work. A complex mesh of fiction and reality, the actors’ discussion was like a therapy session, ranging in subject from Fujiwara’s childhood memories to ways in which the play could be “an exorcism” for things not said at the reunion. Peppered with dark humor, the work culminates with the cathartic smashing of the tea set.

In recent years, Fujiwara has moved away from the dissection, amplification, and reconfiguration of his own identity, and instead focused on those of others. The shift was a conscious one: “I realized there was a way people understood my work—‘The guy that does the autobiographical narratives’—and I wanted to avoid that branding,” he said. “Working with myself is always interesting to an audience, but I wanted to destroy that fetish. That's what I was trying to do by undermining those biographies, but it had the opposite effect. So I removed myself and started thinking about how to expand the thinking I’d developed as ways of approaching bigger issues, and more dangerous, higher stake topics. It’s all a game of expanding the self, or making a more complex vision of what a self is.”

Partial installation view of Joanne, 2016/2018, three free-standing aluminum-clad structures, digital prints, lightboxes, LED monitors screening video:

12 min 6 sec, overall dimensions variable, at "Joanne," Arken Museum of Modern Art, Ishoj, 2019. Photo by David Stjernholm. Courtesy the artist and

Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Fujiwara’s high school art teacher, Joanne Salley, embodies precisely the multifaceted identity the artist is known for profiling in his later projects. A former beauty queen, artist, teacher, marathon runner, champion boxer, and, in her own words, “chameleon,” her complexity was reduced to that of “Topless Teacher” in the British press after students at the school where she taught found and circulated photographs of her taken in private. “She’s been treated like a total cardboard cutout by the press. She basically became a cartoon,” said Fujiwara. “I think The Simpsons are treated with more complexity than she has been.” Comprising images by fashion photographer Andreas Larsson and a film, Joanne (2016/2018) is a portrait of a woman seeking to rebuild her public image. The meta-documentary is heavily commercial in approach: we watch Salley consult with a PR firm, and the film makes full use of cinematographic signifiers of “authenticity,” such as behind-the-scenes footage, handheld shots, and selfie videos. These tools are used to present contrived, curated snapshots of Salley’s identity. All metaphors for her authentic self, the images span the figurative—Salley in the boxing ring, dozing on a couch, eating avocado on toast in a sun-drenched kitchen—to the literal: unfurling a blank canvas, posing with a chameleon, and in the film’s closing scene, actual mudslinging. Cutting through the marketing gloss, we learn the devastating impact the incident had on Salley as she walks the grounds of her former employer. More nuanced than the one-dimensional victim-and-deviant portrayed in her photo scandal, Fujiwara’s Joanne is an uncomfortable watch. Manipulating identities, the work reveals, is multidirectional.

Highly self-aware, Joanne exploits the tricks and tropes of an image-centric society, pitching the complexity of identity against the superficiality of image. “When I think about how the world became this marketing nightmare, where everything is a marketing opportunity, and the effects that has on authenticity or experience, I find comfort in the fact that this whole idea was created by artists,” said Fujiwara. “That was the notion of conceptual art: to name and give form to the abstract or immaterial. It was an amazing thing for artists to reveal—that humans can latch on to that value—and marketers learned from the artists to sell an atmosphere, a mood, or a feeling. Things that people want to buy into.”

This was the starting point for Fujiwara’s most controversial series, which he started in 2017 and is centered on the capitalistic campaigns that have been constructed around Dutch diarist and Holocaust victim Anne Frank. Calling on the artist’s architecture background, the series’ first iteration, titled Hope House (2017), is a full-scale reconstruction of the house that Anne Frank lived and hid in during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. Debuted at Dvir Gallery, in Israel, the work was inspired by a toy model of the home, purchased in the gift shop of the Anne Frank House museum. The building is as much a site of literary pilgrimage for millions inspired by Frank’s story as it is a tourist attraction in Amsterdam: staged for visitors, its unauthentic props coexist alongside the ideological purity associated with the diarist, and the enormity of her place in history. “There’s the tragedy of Anne Frank being murdered by the Nazi regime, and then being exploited, sold, and commodified so extremely. I started to investigate her legacy, her simplification, of even her diary being edited to remove anything risqué.”

Installation view of Likeness, 2018, wax sculpture, vintage desk, chair, lamp and objects, handrail, and two-channel video with color and sound: 19 min 34 sec, overall dimensions variable, at the Preis der Nationalgalerie exhibition, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2019. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy the artist; Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv/Brussels; Gio Marconi, Milan; Taro Nasu, Tokyo; and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

The second iteration of Fujiwara’s investigation into the pull of Frank’s image, co-opted and capitalized on as a symbol for peace, is Likeness (2018). It comprises a life-size model of the diarist sat at her desk, smiling at her audience, and is a copy of a wax statue at the Berlin branch of the popular waxwork museum Madame Tussauds. As with other projects, Fujiwara worked alongside material specialists to create the dummy: “There’s always a philosophical approach to production: what does it mean that something is made in this way, and what does the producer making it mean?” In the case of Likeness, he hired a former employee of Madame Tussauds, “who knows what discussions go into how to design a young girl in color and in 3D who we only have black and white photos of. How do we choose her hair color? How do we make her look Jewish enough? White enough? Appealing enough to a mass audience? There are all these horrific questions you start going through, which I found out about because suddenly the wax-figure maker is bringing me sets of eyeballs so I can choose what color Anne Frank’s eyes should be.”

Women have been front and center of Fujiwara’s artistic practice. In addition to Joanne Salley and Anne Frank, Marie Antoinette has also been a subject of the artist’s investigations. First presented at Tokyo’s Taro Nasu gallery in 2019, “The Antoinette Effect” featured A Dramatically Enlarged Set of Golden Guillotine Earrings Depicting the Severed Heads of Marie Antoinette and King Louis XVI (2019). The oversize fashion accessory alludes to the last queen of France’s commercial appeal, even in gruesome death. In the 18th century, Marie Antoinette became one of the first people whose image was duplicated and circulated, if not accurately then consistently, thanks to the invention of the printing press, emerging as an early media personality. Yet with its relaxed hair and natural complexion, Fujiwara’s wax model Marie Antoinette Head (2019) appears so much softer, and more human than the high-haired and ostentatious queen of the history books. Impaled on a metal pole, it might be severed and spiked post-execution, or the crowning component of a commemorative dummy. Fujiwara’s profile focuses on the ripple effect around the icon, and the industries her own reportedly outrageous consumerism helped activate. Of his tendency to showcase women, Fujiwara said, “For large swathes of history, women have been literal objects: tradable commodities that are married into families to produce children. More than half of the world’s population has been objectified in this way, which brings with it histories of aesthetics, thingness, and body shape—everything that we’re now trying to understand, reappraise, shake off, reconfirm. When I look at women historically, I see a pattern of how we’ve moved as a society toward [where we are now], much more clearly than through the history of men.”

Fujiwara’s latest body of work is centered on Who, a cartoon bear on a quest for identity in an ever-expanding universe of tableaus and social settings. Who pivots from Fujiwara’s prior investigations into society’s propensity and predilection for reductionism, as seen in the simplification of Anne Frank, and the commercialization surrounding Marie Antoinette’s image. “Reduction often happens to the most complex and horrific things: violence against women, injustice, the Holocaust—it’s the worst things that we want to find the simplest icons for, as a way to make them consumable,” he said. “In the past I’ve dealt with people who have become like cartoons. But what if I make a cartoon that then walks into the real world and sees it in this reduced way that’s essentially already there? The abundance is there, so why not feast on it.”

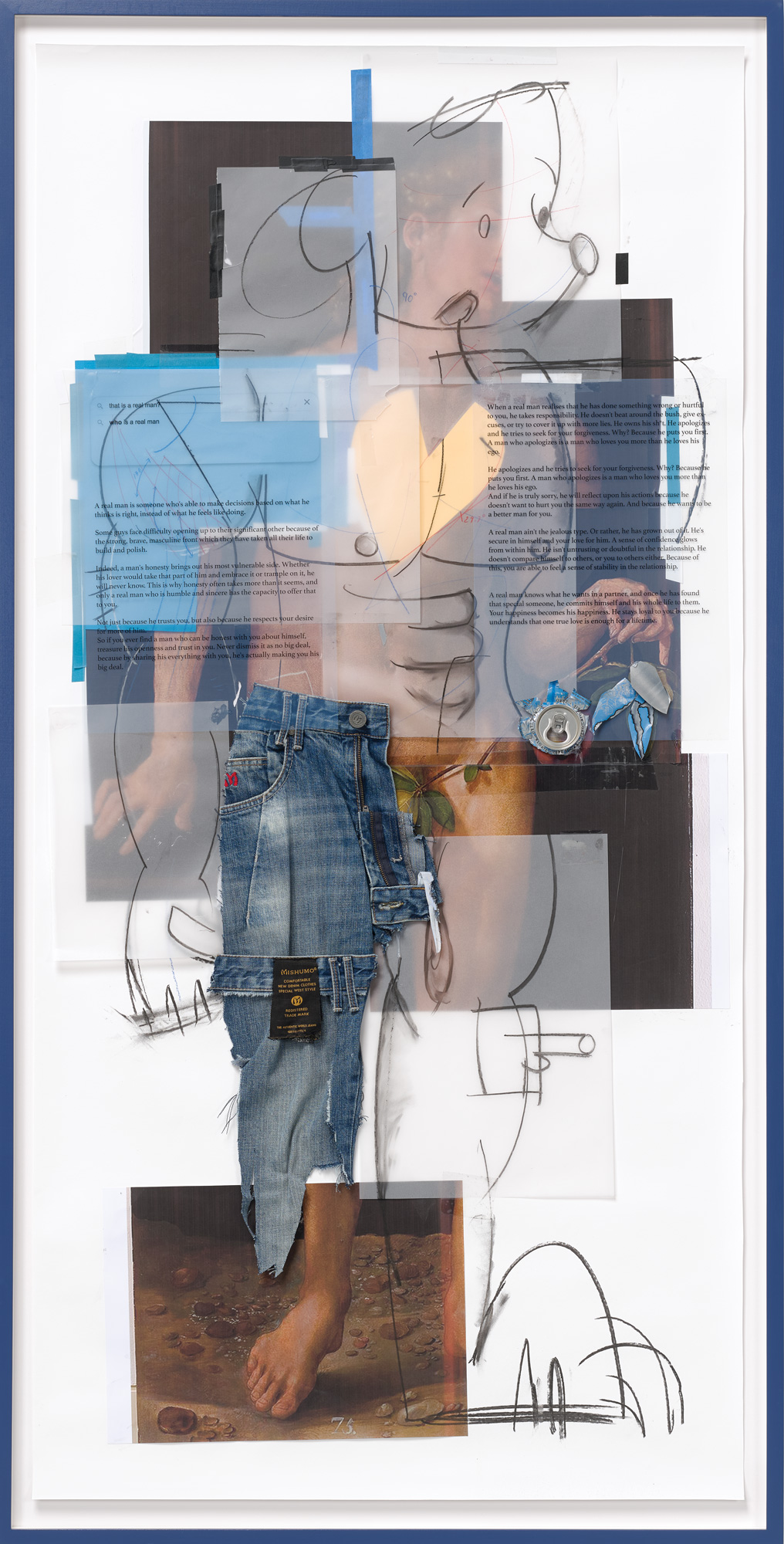

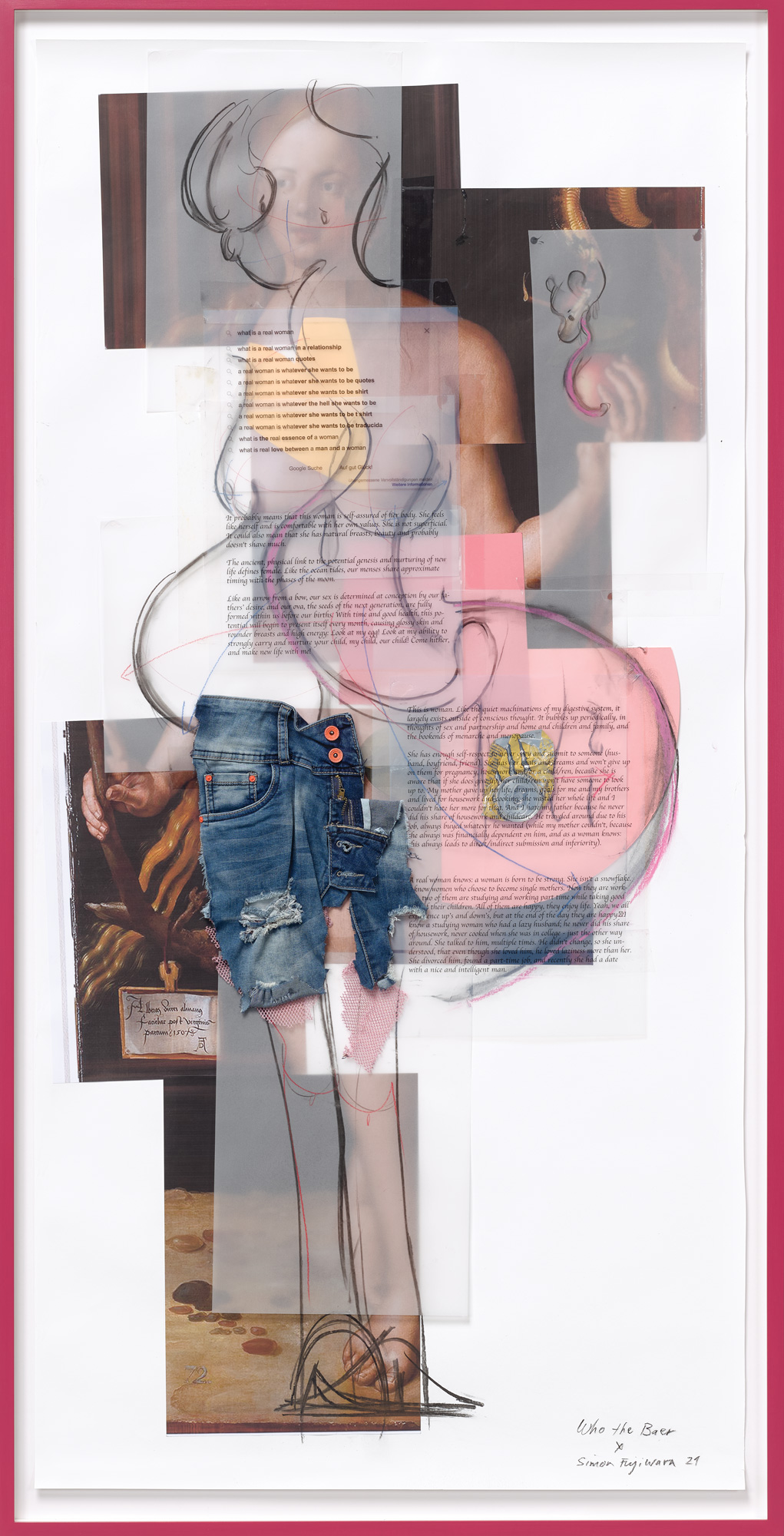

In contrast to the highly polished productions that characterize Fujiwara’s earlier career, Who’s aesthetic is disarmingly unsophisticated. “Who came out of lockdown,” the artist explained. “Suddenly I was in total solitude, and I thought, I can make whatever I want. I always have, but they’ve been these grand productions involving film crews, producers . . . So I asked myself, what can I do with my own hands?” Starting from charcoal sketches (“apocalyptically, I thought if the world is ending there are going to be lots of burned trees, so this is a material that won’t fail me”), Who’s evolution is correlated with the pandemic and ongoing social movements, including #MeToo and Black Lives Matter. “I was watching the whole world shift, but through my iPhone: people were posting about their politics or the clothes that they’re wearing, as gender was collapsing, race exploding, and the whole world order was being questioned. I wanted to respond to these images.” The juxtaposition of fragmented visuals, particularly in German Dadaist Hannah Höch’s interwar photomontages and the collage works of American artist Martha Rosler, who used the technique to protest the Vietnam War, struck him as a fitting approach: “It felt like a similar response to trauma, and a great way to think about this moment.”

Who’s Original Sin?, 2021, inkjet print, acetate paper, fabric, aluminum cans, pastel, and charcoal, 179 × 91.5 × 4.2 cm each. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Who’s Original Sin?, 2021, inkjet print, acetate paper, fabric, aluminum cans, pastel, and charcoal, 179 × 91.5 × 4.2 cm each. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Who is a jeans-wearing bear, with a yellow heart on their chest, prominent ears, long tongue, and cute, upturned snout. But beyond their image, Who is completely undefined, and without gender, beliefs, or sexuality. Their purpose, pursuit, and joy is appropriating identities by assimilating an ever-expanding world of images. The ongoing series has seen Who’s likeness superimposed onto figures from climate activist Greta Thunberg and former United States president Barack Obama, to reality-TV star Kim Kardashian and the Easter Island statues. They have appeared as Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c, 1503) and in Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907–08), and overlaying the Sydney Opera House and the Bilbao Guggenheim. “Who mirrors our times where trying to be rational, find a position, an argument, or identity is becoming an absurd outdated quest that isn’t really serving us,” said Fujiwara.

Who made their institutional debut in April 2021 at Fujiwara’s solo exhibition “Who the Bær,” hosted by Milan’s Fondazione Prada. There, the character appeared throughout a winding, bear-shaped labyrinth made of cardboard, in collages, drawings, and models. Who has also been given their own Instagram account; a line of merchandise in partnership with streetwear and media brand Highsnobiety; and took center stage in Esther Schipper gallery’s first exhibition of 2022, “Once Upon a Who,” in Berlin.

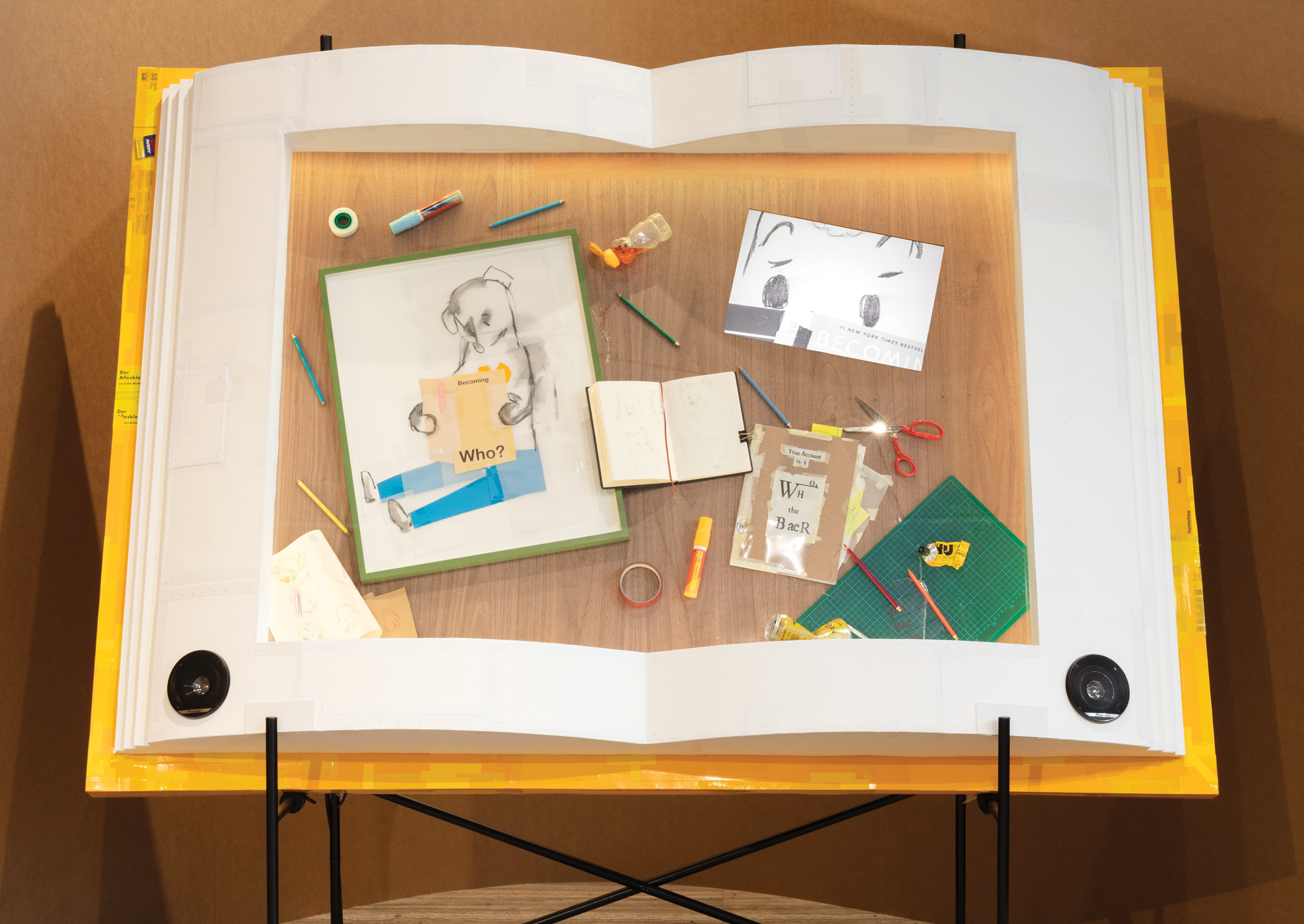

A True Account of Who the Baer, 2021, multimedia sculpture: sketchbook, drawings, paper collage, honey bottle, aluminum can, cutter, scissors, scotch tape, pencils and markers in cardboard frame, metallic base, video on monitor, speakers. Video length: 2 min 3 sec. Video attribution: Andrea Rossetti, Peter Klashorst; Derek Bridges; Viking/Penguin Random House; Kevin Phillips / Devanath/Pixabay; monkeybusinessimages / iStock by Getty Images; VintageSnipsAndClips / Pixabay. Music credits: Ghostly by Paul Mottram, Audio Network/SIA. At "Who the Baer," Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2021. Photo by Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy the artist and Fondazione Prada.

Although Who’s celebrity has grown since those first lockdown charcoal drawings, the series’ homespun quality remains. When I visited Fujiwara at the end of 2021, we watched a stop-motion animation of a poem introducing Who and their adventures that was later featured in the Esther Schipper show: “I hired a voice actor but it just wasn’t right, so I ended up doing it myself,” he said. His Berlin studio is all glue guns, cardboard, and Perspex sheets, with a recent creation—a crude mock-up of Who as Henri Matisse’s iconic Blue Nudes (1952)—propped on the floor. Fujiwara is clearly loving the immediacy of the crafting, making, and doing that goes into Who. “The [works] have to have energy, not quality. Who just wants to respond to all these images. It has to be fast and visceral,” he said. “There’s something about Who that revives one’s belief in the world—you can use everything, it’s all up for grabs. I just listen to what Who wants and they guide me. It’s usually the simple things, which is nice because it means I don’t have to think so much.”

.jpg)