Manila: An interview with Cian Dayrit

By Nicole M. Nepomuceno

Full text also available in Chinese.

CIAN DAYRIT, Valley of Dispossession, 2021, objects and embroidery on fabric, 213 × 183cm. Courtesy the artist and Nome Gallery, Berlin.

How would you summarize life in Manila in 2021?

It was a rollercoaster, to say the least. Everyone faced their fears every day. There’s a collective anxiety, which is not so different from any other part of the world, but specific to the Philippines are the systemic imbalances in our culture and economy. This tension or sustained collective anxiety needs work in terms of contextualizing and understanding. Why do we have this thorn latched in our throats when we wake up? We need to figure out ways to understand it together, because the general symptom of the times is that there’s so much disinformation, which the state and other centralized bodies are banking on as an investment to stay in power.

How do you think the pandemic and this collective anxiety have impacted cultural practitioners?

Cultural workers are part of the general working class but are in a more precarious position, with no job security. For example, performers and gig workers experienced heavy defeats during the lockdown because there were no productions, performances, or mass gatherings—their bread and butter.

For the visual arts, the industry has remained unstructured and reliant on the rhetoric of the market. What is a good investment? It is still being defined within neoliberal frameworks, as it always has been. Exhibitions, commercial galleries, and art fairs carry on, they just move online. There are even new ones, like Cebu’s first Visayas Art Fair (11/25–28). But only a very, very small percentage of the population has the time to go out, experience, and talk about art, let alone buy art. We can say that experiencing and consuming works can also just entail spending time with a show, but in the Philippines, when most of the population has no time—and time is part of access—to go to a gallery, it makes us question: Who are we doing this for?

Now more than ever, there’s motivation for artists to contribute to a show or campaign that is for a cause, like a fundraiser for victims of Typhoon Odette. Some shared calls for donations while other artists pledged a percentage of their artwork sales. There were also artist-initiated fundraisers collecting bail money for arrested individuals, as well as on- and offline solidarity music performances for women, political prisoners, farmers, and others. This is a good opportunity for cultural workers to find ways to be involved, but helping out in that sense is limited because it’s responding to immediate needs. What I’m also interested in is how artists can have a more sustained involvement in solidarity work that’s not just based on when the next typhoon is.

Your practice involves counter-cartographies wherein marginalized historical and geopolitical perspectives are brought to the fore. Grounded in collaborations and conversations with communities who have a lack of access to rights, resources, and representation, your work is also a form of solidarity. What did you work on in 2021?

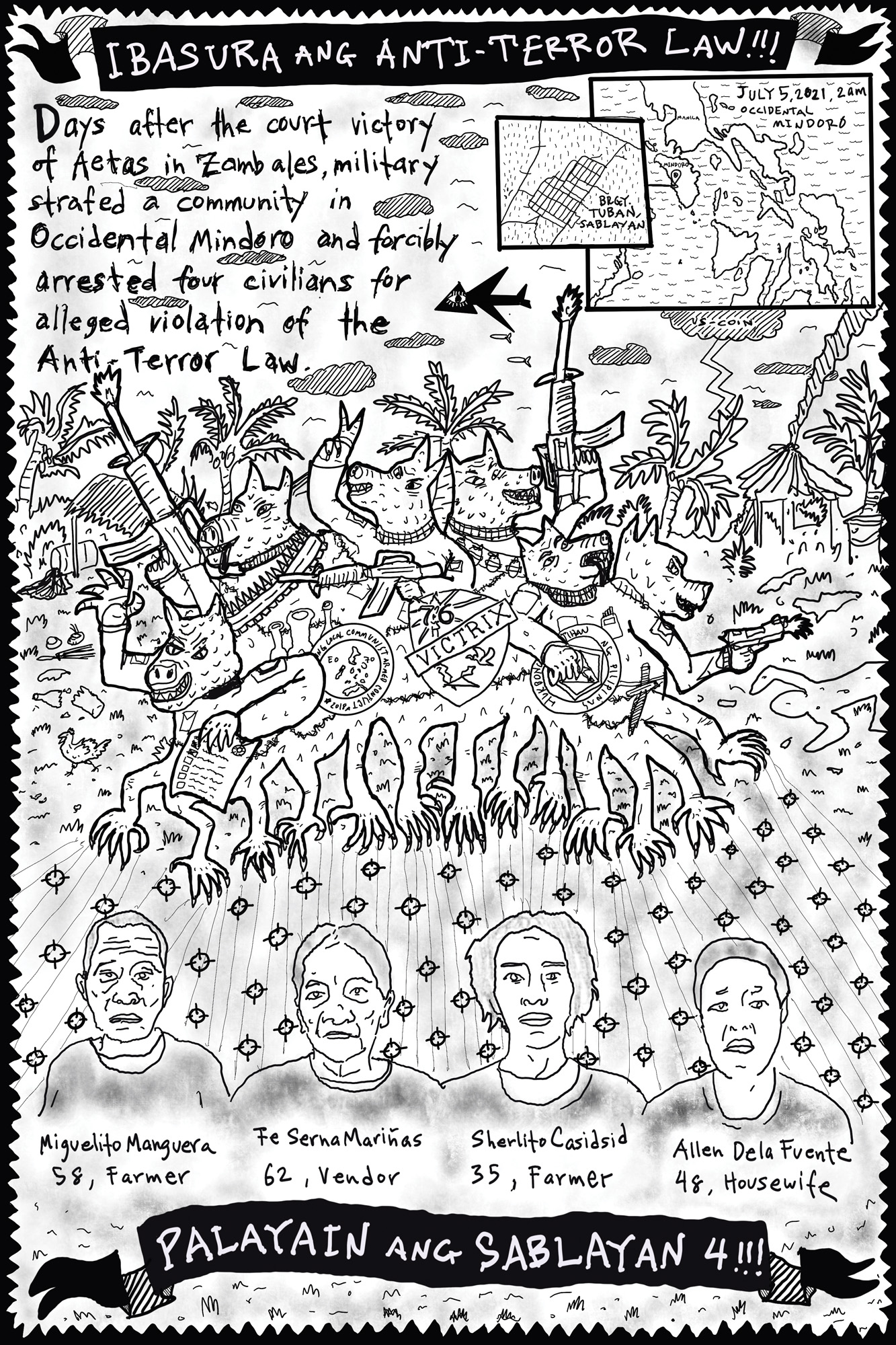

CIAN DAYRIT’s digital drawing based on a factsheet detailing the arrest of four farmers in Mindoro on July 19, 38 × 25cm. Courtesy the artist.

There’s a project that hasn’t materialized yet with activists from Southern Tagalog. The regional chapter of the Karapatan human-rights group gave different artists factsheets about human-rights violations that we’re supposed to make works out of, and my factsheet is on the arrest of four farmers in Mindoro for allegedly violating the anti-terror law. I was looking for other references to the case but there was only one report published by Rappler that was based on the same factsheet that I had. That’s when I realized how rampant these cases are—there’s so much happening under our noses. I also realized how big a responsibility is given to me, but what can I do as an artist? Make a drawing? So, I made a drawing. I can only hope that the drawing spreads this story, one out of many, and foregrounds people’s inherent detachment toward issues happening outside the city, outside our consciousness. I hope people find it within themselves to let it bother them, be uncomfortable, and question the status quo. Somehow, you feel a bit safer if people are concerned and anxious. What we need to do is reclaim this ability to produce affect, to angle our conversations to a collective anxiety based on care for each other, rather than being scared into a corner.

Photo of Tondo Community Pantry at 1350 La Torre Street, Tondo, Manila. Courtesy Tondo Community Pantry.

What artworks, exhibitions, or other cultural productions have been important to you in 2021?

What comes to the top of my head are social-media initiatives, like Tarantadong Kalbo’s drawing of a dissenting fist, Tumindig (2021), which people could personalize. I would also say the community-pantry phenomenon, which artist Ana Patricia Non started in April in Quezon City with a single cart offering supplies such as rice, vegetables, and canned goods according to a “give what you can, take what you need” policy. These are all cultural work.

How is a community pantry cultural work?

It’s cultural work in the sense that it deals with gestures that influence people’s perceptions of each other, space, power, and access. It gets people to talk, communicate, collaborate, and participate—these actions are at the core of “culture.” We need to broaden the idea of cultural practice beyond what is in museums or magazines, to include the everyday movements of people. The economy, politics, and culture are intertwined, and, actually, in today’s circumstances we are realizing that it is possible for one to influence the others.

Non started this mutual-aid practice of sharing food and it immediately proliferated. Some pantries sustained for a long time, others just for a bit, but that’s pretty much how mutual aid historically, culturally, and politically functions anyway. There’s a kind of performativity in how it reacts to or corrects what authorities fail to provide, wherein people take it upon themselves to help each other. People so quickly followed suit not because it was patok or cool to do so but because it was just so logical. That is the beauty of it—people realizing the logic of helping each other in the absence of intervention from the state. As cultural workers or knowledge producers, it is our job to think about and articulate how people can make everyday revolutions.