Kassel: documenta fifteen

By HG Masters

Full text also available in Chinese.

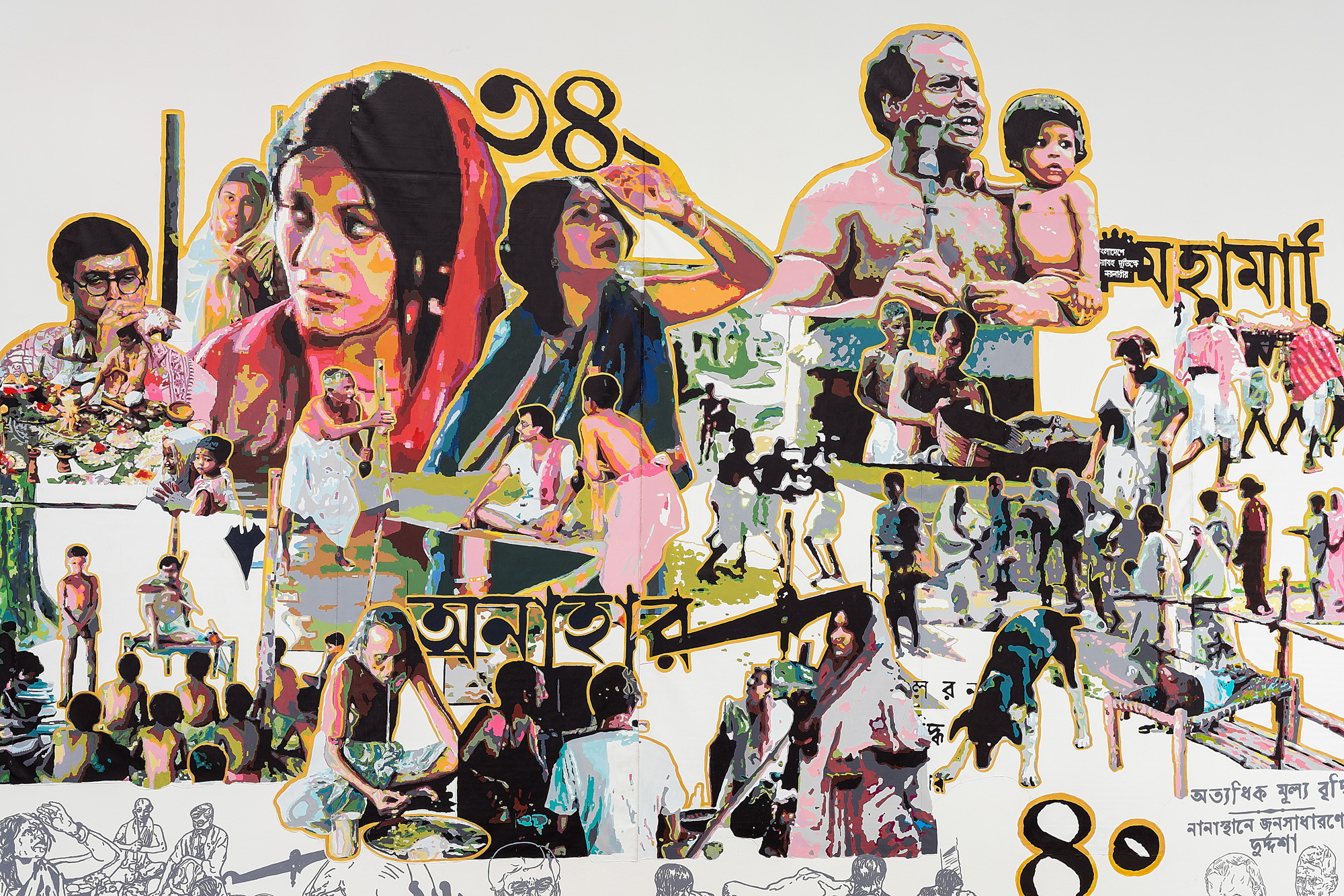

BRITTO ARTS TRUST, Chayachhobi, 2022, painted mural. Photo by Nicolas Wefers. Courtesy the artists and Documenta, Kassel.

In their December 2018 proposal for Documenta, ruangrupa started with the question of how they—an artists’ collective from Jakarta—might further the mission of Gudskul, their new educational initiative (founded with two other collectives), to spread the “virus of collectivism.” Aware of the dependency of cultural organizations on an international art-funding system dominated by ex-colonial powers such as Germany—which perpetuate imperialism through, in their words, “asymmetrical and extraction-accumulation logics”—ruangrupa proposed to make Documenta’s “pool of resources” available more broadly through the koperasi model of a “non-capitalistic democratic economy,” which (as envisioned by Indonesia’s first vice-president Mohammad Hatta) is derived from the Indonesian village practice of the communal rice barn, known as the lumbung. This ultimately led ruangrupa to devise a decentralized structure with nine groups of collectives and artists, known as “mini-majelis,” through which resources were shared to the participants, who ultimately determined what they themselves wanted to do in the context of documenta fifteen.

The realization of ruangrupa’s decentralized model in Kassel produced a mega-event that could be better thought of as a congress or festival of collectives and artists engaged in social-practice initiatives both locally and around the world, rather than a curated, large-scale international exhibition, static and readymade for an audience. For art viewers accustomed to the retail-store mode of art-viewing akin to browsing merchandise—common today across most biennials, art fairs, and white-cube exhibitions—documenta fifteen posed a challenge or even an affront. Visitors were compelled to accept that to a large extent they are not the artists’ primary audience—that being the communities with whom the collectives work and/or are rooted—and that a more engaged form of participation might be required beyond the initial exhibition encounter.

Reflective of ruangrupa’s aim to make the event an experiment in resource-sharing and real-time collaborations, the sites of documenta fifteen were continuously active across the 100-days in Kassel. A single day’s program might include the 15-minute morning “kick-start” session; a midday “conversing, fooding” event at PAKGHOR, the social kitchen by Bangladesh-based Britto Arts Trust; presentations by Gudskul workshop participants; an hour-long Daydreaming Workshop by OFF-Biennale Budapest; a talk on “Intellectuals and Revolution. Debates around freedom of creation in Cuba (1959–1971)” from the Instituto Internacional de Artivismo Hannah Arendt; a tour by Erick Beltrán of his display at the Museum for Sepulchral Culture about “translating the image of power”; a screening by the Subversive Film collective of Japanese films about the Palestinian resistance movement; and an “Indoqueer diaspora clubnight” organized by Party Office b2b Fadescha.

Even the displays were largely oriented for durational public engagements. Documenta Halle was consistently buzzing, with intrepid skateboarders using the ramp designed by Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture and visitors handling their traditional shadow puppets. The giant printing machines of the lumbung press were consistently in action, while viewers browsed Britto Arts Trust’s ersatz bazaar of handmade replicas of foodstuffs beneath giant murals of figures from Bengali cinema, or watched the ultra-low-budget action films of Kampala slum-based Wakaliga Uganda (also known as Ramon Film Productions). The Fridericianum, re-dubbed “Fridskul [Fridericianum as School],” was home to the unfolding workshop and discursive activities of Gudskul, with half the ground-floor devoted to RURUKIDS, a space for creative activities for children. There the tone was often one of critical irreverence. Dan Perjovschi adorned the neoclassical columns with his idiosyncratic text-drawings, while one of many light-box signs around Kassel for the fictitious Kaliphate Fried Chicken franchise, created by Hamja Ahsan, was bolted to the exterior. Richard Bell mounted on the roof a large LED display showing the ever-compounding debt of quadrillions of dollars owed to Indigenous Australians, while his Tent Embassy (2013– ) was pitched in the middle of the 18th-century Friedrichsplatz.

FAFSWAG, Atua, 2022, augmented-reality sculpture, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artists.

While the iconoclastic, decolonializing spirit overturned the sanctity of the white cube in Kassel, many documenta fifteen participants remained squarely and poignantly focused on communities in crisis. The Komîna Fîlm a Rojava initiative, for instance, records musical and oral traditions in the autonomous region of northern Syria, where ethnic minorities have been under threat from regional states. The Baghdad-based artists formerly part of the Sada initiative (2011–15) reflect on their treatment in the wake of the American-led wars and occupation in a series of videos. The Palestine collective The Question of Funding organized a mini-survey of the Gaza-based collective Eltiqa, featuring members’ artworks as well as a chronicle of their efforts on a human level just to persevere under the brutal conditions of Israel’s occupation.

Ruangrupa’s efforts at decentralization in the organization of documenta fifteen gave participants the ability to shape their presentations according to their objectives. Higher visibility motivated many collectives. Formed during protests in 2019–20, the Archives of Women’s Struggles in Algeria reproduces and circulates materials created by earlier generations of women-activists to give historical continuity to contemporary political struggles. Among the several projects by FAFSWAG, an Aotearoa New Zealand-based LGBTQ collective, was a photographic and video presentation of the group’s drag performances, and an engaging augmented-reality encounter, Atua (2022), with a blue-hued, gender-fluid deity. The Haiti-based Atis Rezistans group staged a mini-survey within the St. Kunigundis Church of their artworks and projects from the self-organized Ghetto Biennale, held since 2009. The venue reflected the inspiration that the artists drew from vodou and Kreyol culture, which both incorporate elements of Christianity. In a similar fashion, Taring Padi staged a retrospective of their activities since their 1998 protests against Suharto’s New Order regime. On view were prints, paintings, and documentation of performances that were part of their campaigns against corruption and kleptocracy, and in solidarity with agricultural and environmental groups. Other projects, such as yasmine eid-sabbagh’s 20-year archival project in the Palestinian refugee camp of Burj al-Shamali in southern Lebanon, chose to be less immediately accessible, with a sound installation and short excerpts of text presented in a carpeted room following several weeks of discussions, and a publication forthcoming after documenta fifteen’s run.

Of the many disruptions caused by ruangrupa’s decentralized approach to organizing documenta fifteen, the controversy over the handling of antisemitic depictions in a 2002 mural by Taring Padi might unfortunately be remembered as the most obvious—particularly as rightwing factions in Germany have amplified the incident to delegitimize the entire exhibition, postcolonial discourse writ large, and even to deny Germany’s own colonial history. Meanwhile the actual racialized threats of violence against the participants of documenta fifteen remain unsolved and comparatively little discussed. Despite the reactionary elements that surfaced during these incidents, ruangrupa’s successful transformation of documenta into a platform of community-based practices remapped an international network of cultural actors working on a parallel circuit to the professional art world—much to the disdain of many accustomed to the limelight and those adept at monetizing creative outcomes. Yet far from being alienating to the public, documenta fifteen proved hugely popular in its showcase of art “rooted in life,” illustrating how, even in dire or difficult circumstances, creative communities can find the potential to overcome them.

Partial installation view of TARING PADI’s works at Hallenbad Ost, documenta fifteen, Kassel, 2022. Photo by Frank Sperling. Courtesy the artists and Documenta.

.jpg)