Istanbul: “Once Upon a Time Inconceivable”

By Bala Gürcan

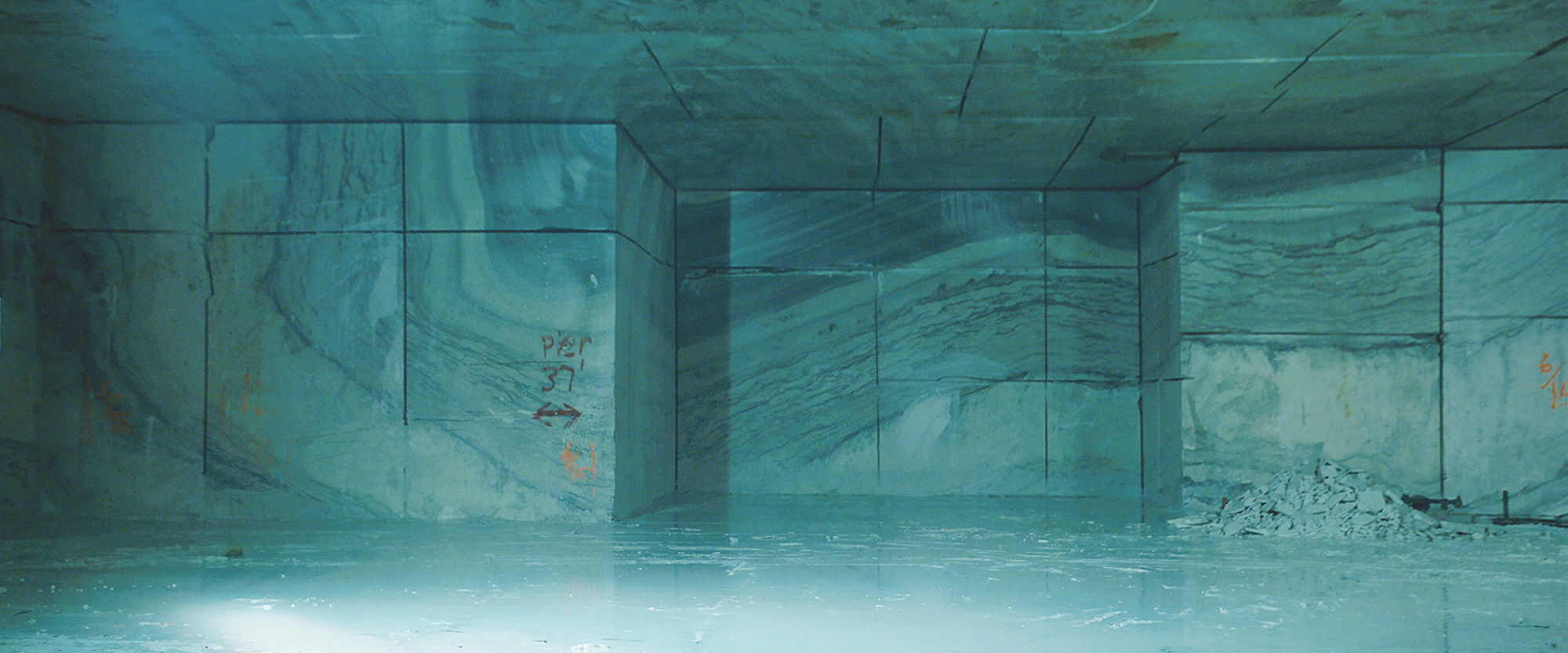

AMIE SIEGEL, Quarry, 2015, still from HD video with color and sound: 34 min. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

“Once Upon a Time Inconceivable”

Protocinema at Beykoz Kundara

Istanbul

Art enables us to comprehend the passage of time in visual and auditory terms, to track the physical marks that it imprints on ourselves and the world. To celebrate its tenth anniversary, Protocinema brought together nine artists for the exhibition “Once Upon a Time Inconceivable,” featuring works that examine perceptions of time and space, woven into and by our collective consciousness. Beykoz Kundura, a derelict Ottoman-era factory that is now a cultural hub and frequent filming location, served as an apt venue, with its layered histories and functions.

At the entrance, Ceal Floyer’s inconspicuous work Viewer (2011–21) invited the audience to look at the venue’s surroundings through a peephole in one of the glass doors. As opposed to a peephole’s regular purpose of allowing one’s gaze to penetrate the external world without giving away one’s identity, the transparent glass frame exposes the onlooker. The permeability of the work calls to mind the omnipresent plexiglass partitions that guard against the spread of Covid-19. Drawing attention to our heightened sense of vulnerability and exposure, Floyer’s work reads well in relation to the difficult task of navigating our defamiliarization with assumed spaces of safety.

Mechanisms of spectatorship are also at play in Mario García Torres’s Spoiler Series (undated), a sequence of paintings spread across the venue that reveal, in big lettering and bold colors, the endings of movies including Inception (2010), Fight Club (1999), and The Matrix (1999). In a 2009 E-flux article, Hito Steyerl noted that as our smartphones increasingly turn into cinematic tools, the resulting images “[transform] quality into accessibility, exhibition value into cult value, films into clips, contemplation into distraction.” The unwarranted spoilers affirm our fragmented engagement with art in the post-digital age, characterized by the attention- deficient presentation and consumption of artistic content.

Amie Siegel’s video Quarry (2015) sheds light on how the value of marble changes as the material moves through its consecutive industrial stages, revealing the function of time within the complex processes of consumerism. Starting off with the extraction of the natural stone from the earth in an underground quarry, Siegel documents the liminal stages as the marble blocks await exportation, and finally embellish the high-end properties of Manhattan. Likewise, Gülşah Mursaloğlu’s Merging Fields, Splitting Ends (2021), in which the rising steam from six vats of boiling water gradually dissolves the bioplastic sheets suspended above, enabling an observation of time and space as dynamic actors in this process of material change. Displaying the prolonged life cycle of archived footage, Paul Pfeiffer’s multi-channel video Orpheus Descending (2001) documents the incubation and hatching of eggs, followed by the growth of the chicks. Recorded and shown over a real-time duration of 1,800 hours, the original video had been installed at the World Trade Center just three months prior to September 11, which adds another layer of temporal significance, as the work is now bound with a traumatic puncture within American collective memory. Zeyno Pekünlü’s Without a Camera (2021) compiles clips filmed by both humans and autonomous gadgets and shared on an open-source online platform. A reference to Dziga Vertov’s 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera, Pekünlü’s work shows how the relationship between the eye and the lens, the subject and the object has changed drastically within the last century. Both works represent the expansive temporal and spatial terrains available in the medium of video today, prompted by the objectified and decentralized gaze of monitors, drones, and algorithms.

“Once Upon a Time Inconceivable” emphasized how technologies have enabled alternative ways of looking, recording, and re-playing— events can be witnessed forward, backward, in parts or in a loop. A powerful tool of preservation, art can bear witness to historical and material processes, and reveal individual and collective transformation. By encouraging viewers to venture beyond the context of everyday perception, the exhibition asked us to re-evaluate our collective interactions with our surroundings, breaking the limitations of chronology and geography, and making space, time, and causality visible in new ways.

.jpg)