Inside Burger Collection: I don’t make art – to call what I do art is already a mistake!

By Johannes Hoerning and Anke Kempkes

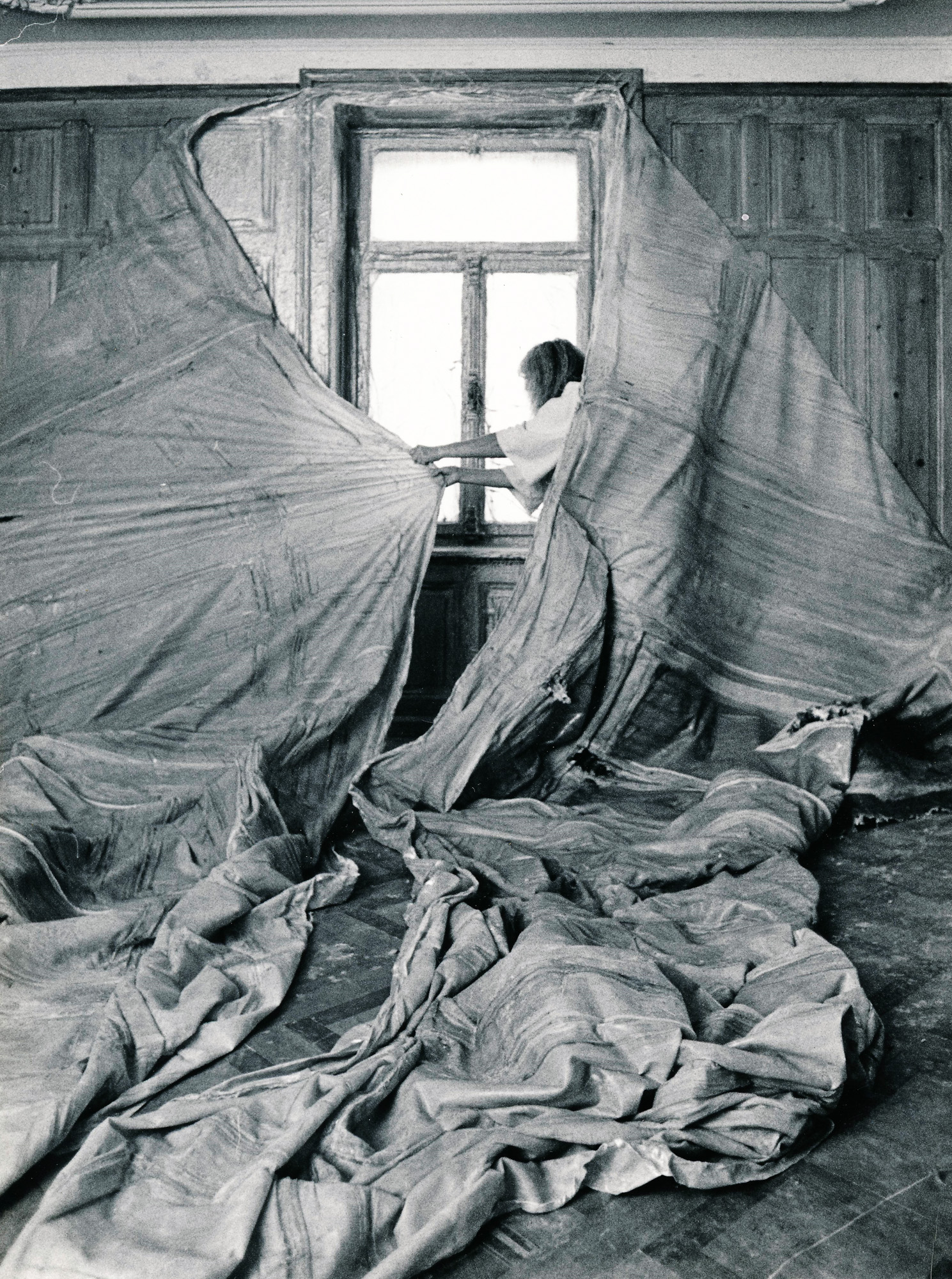

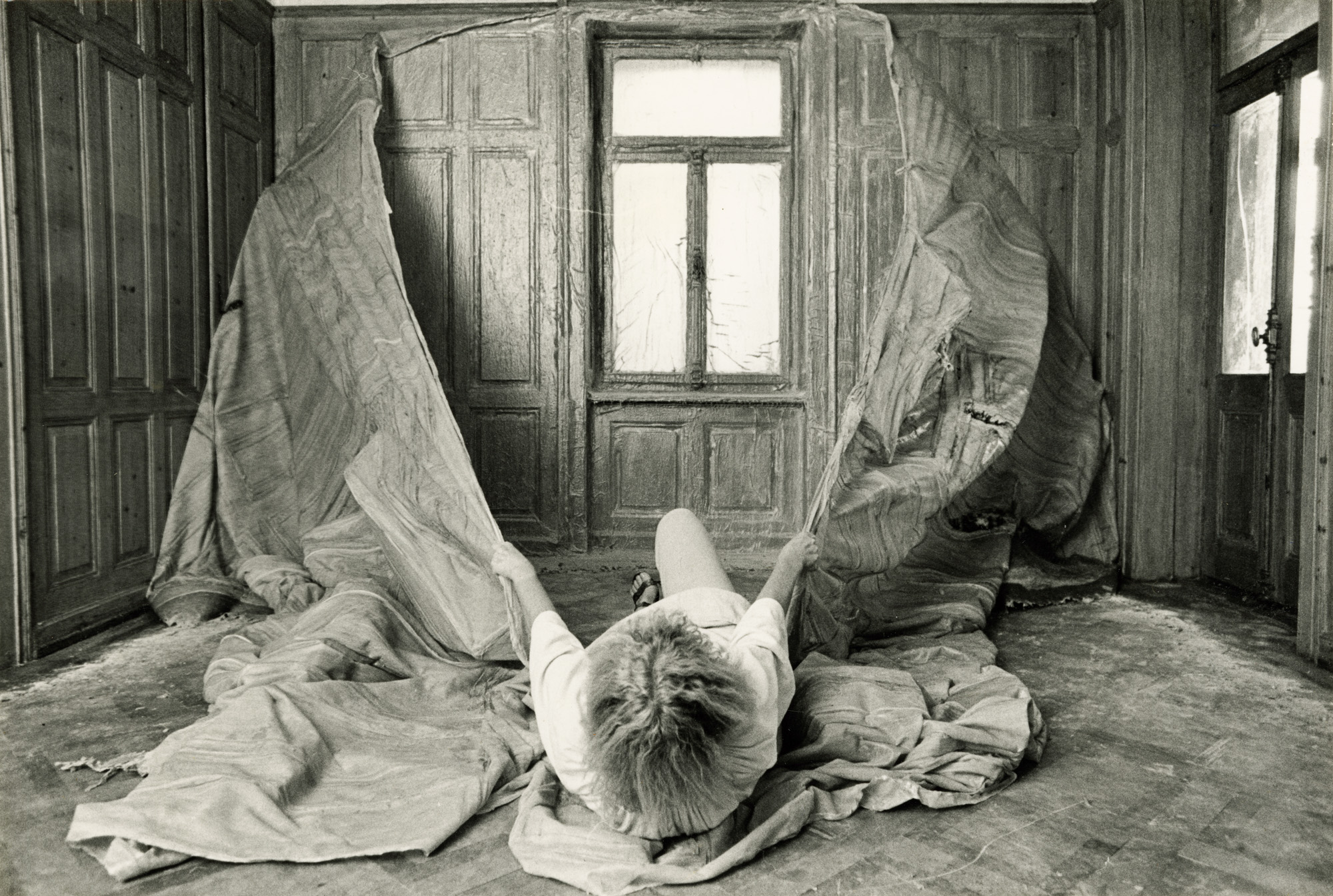

Photo of HEIDI BUCHER‘s skinning process of the Herrenzimmer (gentlemen’s room) in her family home in Winterthur, 1978. Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher.

Johannes Hoerning How should we think about Heidi Bucher’s art? We know from interviews that she rejected calling her work “art,” a familiar sentiment that returns to Duchamp and was loudly stylized by the postwar neo-avant-garde. We also know that she wrote a dictionary to introduce new words—usually hard to translate, with strong onomatopoetic qualities, such as Vermöbeln, Verquappeln, Entquappeln—to describe her practice, which is in itself a rejection of a conventional understanding of art practices. How would you situate Bucher’s Kunstbegriff (notion of art) and her negations?

Anke Kempkes In 1978, during the skinning process—the artist stripping a layer of latex-soaked cloths from the walls creating a lasting imprint—of the Herrenzimmer [“gentlemen’s room”] in her family home in Winterthur, Switzerland, Bucher was interviewed on camera by her son, Indigo. Bucher’s urgent tone turned this conversation into a kind of manifesto of her later work and practice, in which she explains what aesthetic commitment meant to her in this phase of life: “I don’t make art. To call what I do ‘art’ is already a mistake. Art is when something is just honest and pure, and I’ve come a long way . . . I don’t have to repeat it [skinning], because the urgency is over . . . I need to see something drowning, because the skin is something we have to leave behind. And maybe you can live without any environment or surroundings. So when I go far away, to a glacier or into a lake, I am saying: ‘I am at least trying to raise the thought that we might actually forget the environment.’ ‘Drowning’ is the end of a period. And it doesn’t mean that sinking into the water is the very end. It is also the beginning of a new life in a system of our growth. It is a gesture. I have a lake.”1

This vehement but nonetheless poetic statement leaves a strong impression, which not only contains biographical notions but also all major subjects of her mature practice and her very specific situatedness at the time. The negation of “art” in favor of process expands into an existential-aesthetic credo for the necessary cycle of crisis and renewal that she described as “the system of our growth.” Then there features the central principle of the “death drive,” which is expressed by the motif of “drowning” in her work as the condition from which the potential of new subjectivities arise. Finally, Bucher’s statement evokes the motif of water and fluidity—a life without “environment and surroundings.” She longs for a new form of existence beyond the normative pressures of society and cultural significance.

HEIDI BUCHER, Untitled (Herrenzimmer), 1977-79, latex, cotton, 259.7 × 180.3 × 19.1 cm. Photo by Daniel Perez. Courtesy Freymond-Guth, Zurich, and Swiss Institute, New York.

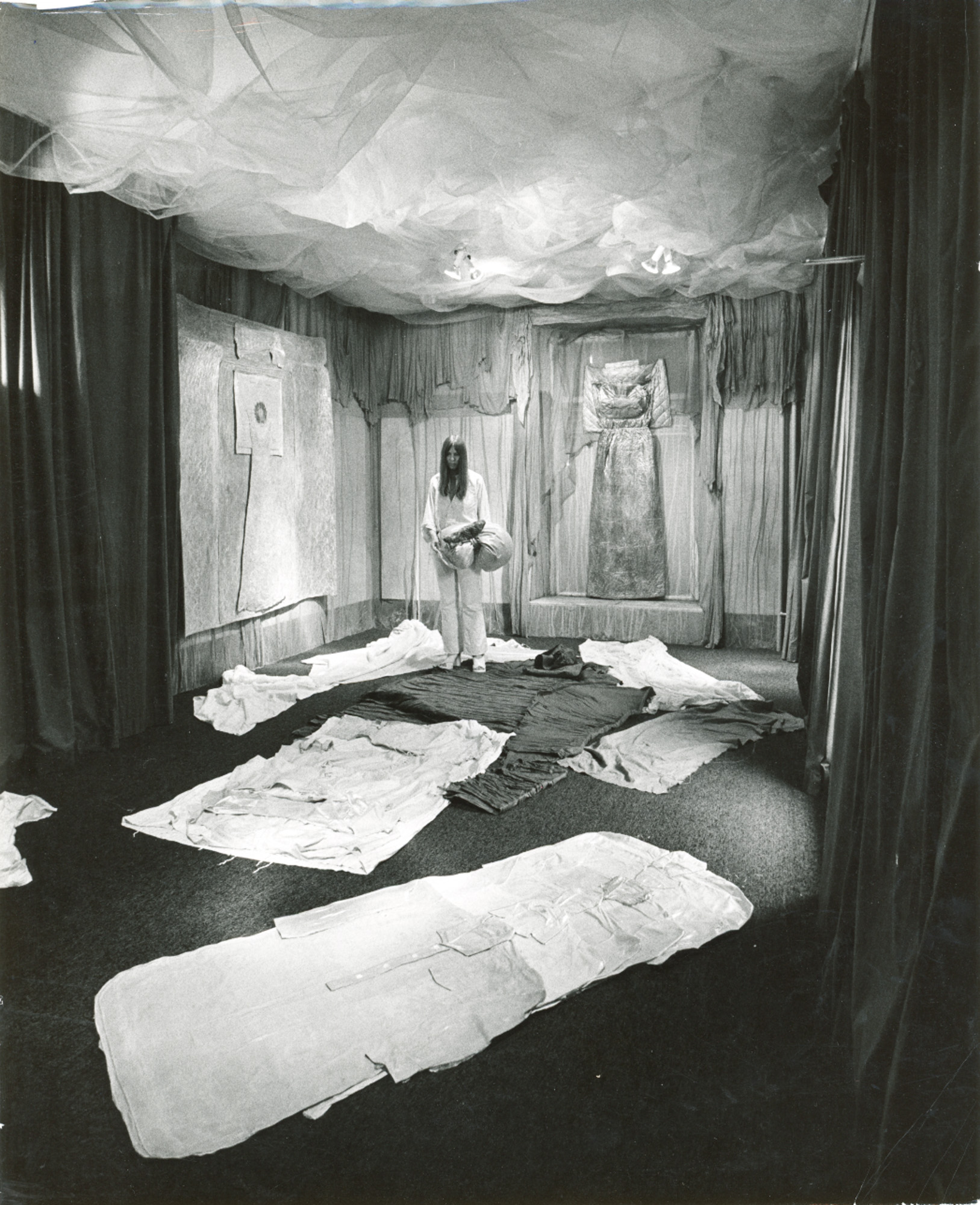

Photos of HEIDI BUCHER’s skinning process of the small glass portal at Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen, 1988. Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher.

Photos of HEIDI BUCHER’s skinning process of the small glass portal at Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen, 1988. Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher.

To elaborate on these rather complex operations: when exhibited as suspended sheets in the museums, the Raumhäute (“room skins,” a word coined by Bucher) look like dead remains. This impression is not merely caused by the effects of the institutional framing, but follows the internal logic of Bucher’s work relating directly to the artist’s resistance to call the act of skinning “art.” She brings to our attention the specific process engaged here, in which one stage is split from the other, each triggering the next—from the skinning, which is the process of psychologically working through the past, to the physical and symbolical “airing” of the skin, a synonym to “drowning.” When Bucher carries the skins outside and elevates them into the sky, she is stripping them from the context of their former environment. When she wraps herself up with them, as in the performance of the skinning of the Sanatorium Belvedere, Kreuzlingen (1988), she performs an act of utopian exorcism. All these acts reinvest the already dead object with speculative possibilities. If we define the first stage of the skinning as crucially driven by the “interception of a psychic principle,” then this stage is situated outside the realm of the institution. The last stage, as another split from the processed object, is the exhibition of the skin in the museal context. Only now it turns into the convention of “sculpture.” Here the skins appear as remains of the constitutive death drive materialized in the beginning of the process. The skins hanging in the museum is a totemic reminder of the act of killing: the deadening of the architecture’s previous symbolic realm.

Installation view of HEIDI BUCHER’s Small Glass Portal [Sanatorium Bellevue, Kreuzlingen], 1988, latex, and gauze, 340 × 455 cm, at Art Basel Unlimited, 2016. Photo by Robert Glowacki Photography. Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher and The Approach, London.

There is more at stake in Bucher’s “non-art”—which sees the rise of a genuinely visionary and existentially driven language—than the anti-bourgeois and anarchic rhetoric known of the historic avant-garde. This is true of Bucher, just as expressed by Eva Hesse a few years prior in her disclaiming statement “to get to the nonanthropomorphic, nongeometric, non-non.”

JH A very good way of interpreting her work and treatment of history is by way of considering alternative temporality. Bucher’s work articulates how we make sense of time in terms of space: changes in aggregate and states of matter of liquid latex, the skinning of the new state of matter from historical objects, and lastly the performative changes in location, from one historical site to, very often, a natural site with its own laws of time. She also does not repeat the process of de-skinning in the same location. While this adds a singularity to each of her larger works, she repeats history by bringing our attention to the meaning of history we assign to these structures embodied in ornaments. We would not understand her work if we did not already have knowledge of the history that she dealt with, and of our relation to that history. In this sense, singularity and repetition stand in a dialectic tension.

Photo of HEIDI BUCHER’s performance with her Body Shells (1972) on Venice Beach, California. Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher.

Still from HEIDI BUCHER’s documentary film of Body Shells, Venice Beach (1972). Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher.

AK As in the work of other female artists of her milieu, we see in Bucher’s work various models of time at work simultaneously, which are closely connected to the very specific and often-fatal circumstances female artists found themselves in at the time.

I’ve talked about the inert structural logic of “circular time” that appears through the complexities and split-off stages of the process Bucher engaged with in her room skins. This notion belongs to the existential dimension of her aesthetic concept, the necessary cycle of death/drowning and new beginnings as a “system of growth” in life and art.

Portrait of HEIDI BUCHER in her studio, Zurich, 1976. Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher.

Another logic of time is connected to personal time, autobiographic circumstances of the artist running tangential to the successive evolutionary thinking of all avant-garde theories, their subsequent historical periodization, and to cultural-geographic belonging. When Bucher is classified today as a “neo-avant-garde artist,” we need to consider various aspects: First, Bucher is mostly associated with the artistic milieu defined in the framework and related discourse of North American art movements. Secondly, when she started making her signature room skins, Bucher was already middle aged and no longer an emerging artist. Thirdly, a distinct rupture happened in her work when she moved from the permissive Californian art environment, impacted by emancipatory new social movements, back to Switzerland with its still deeply rooted conservatism. One could not think of a more radical break: from the gleaming, futuristic, joyously playful, and sexually amorphous Body Shells dancing on Venice Beach in 1972, to the grim environment of the butcher shop in Zurich where the first skinning, Borg, took place in 1976 (and I cannot resist associating a word play here in Bucher’s own style from “cyborg” to “borg”), followed by the room skins of Herrenzimmer, Grande Albergo Brissago (1987) and Sanatorium Bellevue, Kreuzlingen. Her return to Europe was less of a homecoming than having to make new sense of things, a confrontation. This fundamental shift allowed history to re-emerge in her work as a site. And I find your elaboration in Frog Magazine important, as it underlines her engagement with 19th-century bourgeois architecture and connects her signature material, latex, with the colonial history of the harvesting, production, and distribution of rubber.

JH When it comes to Bucher’s personal time, one could compartmentalize her practice accordingly into different phases from 1944 to the late 1980s. After obtaining her seamstress diploma in 1944, she studied under Johannes Itten and Max Bill at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts, from which textile and color studies emerged. She started creating early drawings (draperies, bodies, nudes, self-portraits) in her mid-to-late 20s, before a short period of silk collages. Then in the United States in the early 1970s, where she encountered artists at the Womanhouse (also known as Womanspace) in California, she produced body shells, body wrapping in collaboration with her husband Carl Bucher (whom she married in 1961). Her later practice began with a return to Switzerland in 1973 and divorce from Carl, first with Borg inside her studio in a former butcher shop then the famous Herrenzimmer. What do you make of these ruptures in Bucher’s biography?

AK Speaking of biographical ruptures affecting an artistic career path, in the late 1960s and early ’70s, a divorce wave shook the cultural-intellectual scene induced by the sexual revolution and the feminist movement. Heidi Bucher ended up as a single parent after her divorce from artist and collaborator Carl Bucher and relocated from her considerable involvement and exposure in California to the more backward and peripheral milieu in Switzerland in 1973. These disruptive events inevitably slowed down her practice and career in the mid-1970s. All these “personal” conditions affected women’s work much more drastically than that of their fellow male artists. They were largely kept discreet until women artists directly engaged with the feminist movement and started to thematize these contexts in their art and discourse following the movement’s postulate “the personal is political.”2 But for women who associated themselves with the late modernist and neo-avant-garde movements, bringing up personal narratives in their art was a highly sensible and contested ground. As was any crediting of other women artists’ achievement and any declaration of a female lineage of influence, the fear of further marginalization ran deep. Heidi Bucher’s dedication to Eva Hesse might have been co-inspired by the Feminist Art Program of the Womanhouse Los Angeles founded in 1972. The program, which featured talks and workshops on preceding women artists and writers such as Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Virginia Woolf, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Anais Nin, remained in Bucher’s archive with her markings indicative of what was most significant to her. Such a program was of utmost importance. Not having been able for centuries to positively and consistently refer to a female lineage and legacy in cultural history caused another temporal complication of non-linearity.

In the “chromo-normativity” of hegemonic art historical narratives, male artists used to rely on an unquestioned linear evolutionary account of achievement and discourse surrounding their male predecessors.

With any female lineage largely “invisibilized,” per Paul B. Preciado, such models created a paradox for neo-avant-garde women artists, who were finally about to be recognized and counter-affirmed since the 1970s feminist art movements.

Photos of HEIDI BUCHER‘s skinning process of the Herrenzimmer (gentlemen’s room) in her family home in Winterthur, 1978. Photo by Hans Peter Siffert. Courtesy the Estate of Heidi Bucher.

JH From being invisible, Heidi Bucher has now been “rediscovered” both by institutions and by the market—two spheres that continue to enjoy an elective affinity. The claim to “rediscover” often raises further question: Who rediscovers?

In what language? Who funds the rediscovery and who profits from it? One could go on. In the case of Bucher’s latest retrospective held at a state-run institution in Munich, the curators claimed it as a “rediscovery” of Bucher, specifically as a “neo-avant-garde” artist. By making these claims, the label canonizes and renders her work continuous, linear, and situates her work in relation to the avant-garde, within the framework of modernism. What do you think is the motivation to label Heidi Bucher as a neo-avant-garde artist? I believe that the strongest claim made by Bucher, which none of the neo-avant-garde artists made, is that we still live in the shadow of the 19th century. Her latex skinnings could then be read as demands to reconsider the aesthetic and political shadows of a particular European past. She was interested in the objects and architecture built in the age of capital—the very term “capital” is an invention of the second half of the 19th century. To be sure, many artists of the neo-avant-garde are critical of capital(ism); but none of them, it seems to me, had much interest in the 19th century and questions around historicity in its aesthetic and political dimension, including colonialism, with latex being a product of economic expansion and invasion.

AK The recent efforts to (re)situate Heidi Bucher’s work in the history and discourse of the neo-avant-garde is as reasonable as it is insufficient. These efforts follow the intention of rightfully contextualizing Bucher with artists like Eva Hesse, Louise Bourgeois, Ana Mendieta, or Lynda Benglis. However, this act of canonization—admittedly a recent one recognizing the significant contributions of female artists to avant-garde history—has so far stopped short at the level of the shared embrace of progressive new art materials and techniques, and at the iconographic level, such as comparing Bucher’s focus on architectural sites with Bourgeois’s lifelong occupation with her project Femme Maison.

The term “rediscovery” used in the recent Bucher retrospective poses another problem. This term not only activates its “colonial meaning,” as pointed out by Preciado, but also adds to the paradox of wanting to (re)situate a work into established narratives, the specific parameters and innovations of which were hardly articulated or recognized in their own time and critical contemporaneity. Due to Bucher’s career-inducing period spent in the US, the neo-avant-garde lineage cited in these recent scholarly accounts is one that has taken place in the East and West Coast milieus, while the shift that became constitutive for Bucher’s innovative mature work took place with the return to the cultural-political framework of Switzerland and central Europe of the late 1970s and ’80s.

But there is more complication to this canonization. When we follow the definitions given to the term “neo-avant-garde” foremost in Hal Foster’s influential 1994 study “What’s Neo about the Neo-avant-garde?” we could affirm that Bucher’s room skins in particular fit the discursive mold. For Foster, the neo-avant-garde of the 1960s brought the claims of the “institutionally repressed” avant-garde to full fruition, investigating the institutional in “its perceptual and cognitive, structural and discursive parameters.” In Foster’s model, the core concern of the neo-avant-garde is its focus on “institutional critique,” recognized as a distinct genre in art history since the 1980s. We already argued that Heidi Bucher’s room skins targeted the “institution” of architecture and history itself in a Foucauldian sense as sites where normative subjectivation takes place. In that sense Bucher’s work fits the definition of the concerns and concepts of the neo-avant-garde as understood by Foster.

JH But why does her work still seem to evade processes of categorization?

AK Indeed, her work never sits quite right in such “hardened” historic definitions. Why does it take stage with such “immediate authority” and “extraordinary originality” as Rosalind Krauss had detected in Eva Hesse’s Contingent (1969), a work that bears such intriguing prefiguration to Bucher’s subsequent skin installations? In my opinion, there are, speculatively, unlimited reasons: for one, it is related to the cultural-geographic shift of Bucher’s work from the US to Europe which exposed her to radically new (post-avant-garde) sites and agendas. With her focus on architecture and allegorical processes, Bucher pre-conceptualized in the late 1970s some of the most critical and transgressive tropes of the postmodern. Secondly, it deals with the undertheorized potentials and specifics of what I call a “female avant-garde” inside the dominant parameters of the avant-garde. For example, Krauss detected in Hesse a concern—shared by other female post-Minimalists—to come to terms with the “subarticulate,” matter in its “preformal” condition, dimensions in her work that seemed to follow completely new and independent trajectories. These are some of the main reasons why Bucher’s work demands a rethinking of existing categories beyond the familiar neo-avant-garde narrative.

1 This quote is an edited part of Heidi Bucher’s statements in the 1978 video. Transcription and translation by Anke Kempkes.

2 One of the first texts of the “emancipation movement” in the German-speaking milieu was the novel “Häutungen” (“Skinnings,” 1975) by Swiss author Verena Stefan which made wide furore. The autobiographic novel engaged in “dreams, poetry and analysis” with (lesbian) sexuality and consciousness raising processes. It might have had an impact on Bucher upon her return to Switzerland coinciding with her first “skinnings.”

Heidi Bucher (born 1926 in Winterthur, died 1993 in Brunnen, Switzerland) was a Swiss artist known for her experimental performative work, architectural latex skinnings, and transformation of private and public spaces. Her work has recently been the subject of a large traveling retrospective titled “Metamorphosen,” which began at Haus der Kunst, Munich, from September 2021 through February 2022, followed by Kunstmuseum Bern, April through August 2022, and at Muzeum Susch between July through December 11, 2022.

Anke Kempkes is a curator, art historian and critic with a focus on female avant-garde, 20th-century abstraction, surrealism, queer modernity, and minimal dance, performance, and music in the US neo-avant-garde. She is lecturer at the Zurich University of the Arts. In 2021, she was director of Instituto Susch and curator-at-large at Art Stations Foundation CH / Muzeum Susch. Her recent writing includes essays on Verena Loewensberg, Teresa Murak, Mary Vieira, Sonja Sekula, Stanislava Kovalcikova, and Teruko Yokoi, among others.

Johannes Hoerning is a political philosopher and art historian based in New York and Hong Kong. He is currently completing his PhD dissertation in the history of modern political thought at Cambridge University. Recent writing includes essays on Cao Fei, Heidi Bucher, Meret Oppenheim, Paul Thek, Tetsumi Kudo, and Franz West. From 2018 to 2022, Hoerning was lead researcher at M+ Hong Kong for the museum’s Marcel Duchamp collection and archive, focusing on the history of exhibitions and reception of Duchamp in Asia.