Inside Burger Collection 42: Made Men: Going Back to Steven Shearer’s World

By Dieter Roelstraete

STEVEN SHEARER, The Convalescent, 2006, oil on canvas, 164 × 106.5 cm. All images courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich/New York. Private Collection, Paris.

When I first encountered Steven Shearer’s work in 2004, one could have made the case that it was the matter of manhood that was at the heart of his iconographic concerns. A little more than a decade and a half later, it seems safer to say that it is the question of manhood that occupies that position of undiminished centrality in Shearer’s world: the proverbial can of worms, that is, of “masculinity,” or rather, the proverbial can of worms that masculinity has since become.

Shearer draws, paints, and prints pictures of men both young and old. The number of women that appear in his work can be counted on the fingers of one hand. It is somewhat telling that, when they do materialize, these female figures are subjects in paintings embedded within the artist’s drawings or paintings, seen from a remove, that is, in his meta-pictorial musings, and as compositional challenges rather than as people—see, for instance, Young Symbolist (2013), or The Ornamentalist and Apprentice (2014). Although the history of art does not exactly bear this out, women can be hard to draw for some. I speak from a certain degree of personal experience here: I was an avid drawing enthusiast as a young person, and reasonably good at drawing figures—but not, alas, female figures. I do not know whether this is also the case for Shearer, who is incidentally very good at conjuring his own facial features with the most basic of gestures, and whose continuous allusion to auto-portraiture has been permeating his painterly output for some time now. This is worth dwelling on in the case of an artist as camera-shy, private, and reclusive as he is: few photographs of Shearer seem to exist out there on the worldwide web of jpegs, gifs, and tiffs that has for so long been such a dependable source of inspiration for the artist’s imagery.

With that being said, Shearer only draws, paints, and prints pictures of a particular kind of man, and among those only a handful of figures—archetypes, really—keep appearing throughout his oeuvre, which now spans more than two decades. The best known and most familiar of these personas are culled from the musical netherworld of the global metal subculture, including pictures of bands, portraits of front men, and snapshots of fans. (They or their bands are called Dead, Euronymous, Faust, Mayhem, Morbid Angel, Obituary, and Quorthon.) Consider, for instance, the long-haired, smoking figure featured in Smoke (2005), Drag, and The Convalescent (both 2006), or Hash and Night Train (both 2008); or the arresting profile recurring in the aptly titled Guys & Dolls (2006), Single (2007), and Stairs (2016): spectral revenants in an obsessive fever dream, for the artist’s neo-Fauve aesthetic has certainly grown increasingly hallucinatory, psychedelic even, over the years. They are young, invariably long-haired, beardless, often half-naked, and suffused with the obvious association of androgyny. This is surely the defining paradox of Shearer’s interest in this iconography, when considered against the backdrop of this proletarian subculture’s long history of both casual misogyny and homophobia. Indeed, there are so few women in Shearer’s art in part because there are so few women in the subcultures from which so many of his models hail. The homosocial dynamics of this cultic demi-monde are nowhere better captured than in a photograph of a bunch of Swedish metalheads seated together inside a sauna, which became the basis for Shearer’s 2005 painting Brother, among other works. It is hard to think of an image that more acutely encapsulates the “gender trouble” at the heart of the metal subculture as well as, mutatis mutandis, the art inspired by it: a problematic conception of being male in which the straightforward celebration of many aspects of what we would now refer to as “toxic masculinity” exists, more or less comfortably, alongside a preoccupation with bodily aesthetics and self-imaging that both complicates and actively undermines such exact monolithic, muscular notions of manhood.

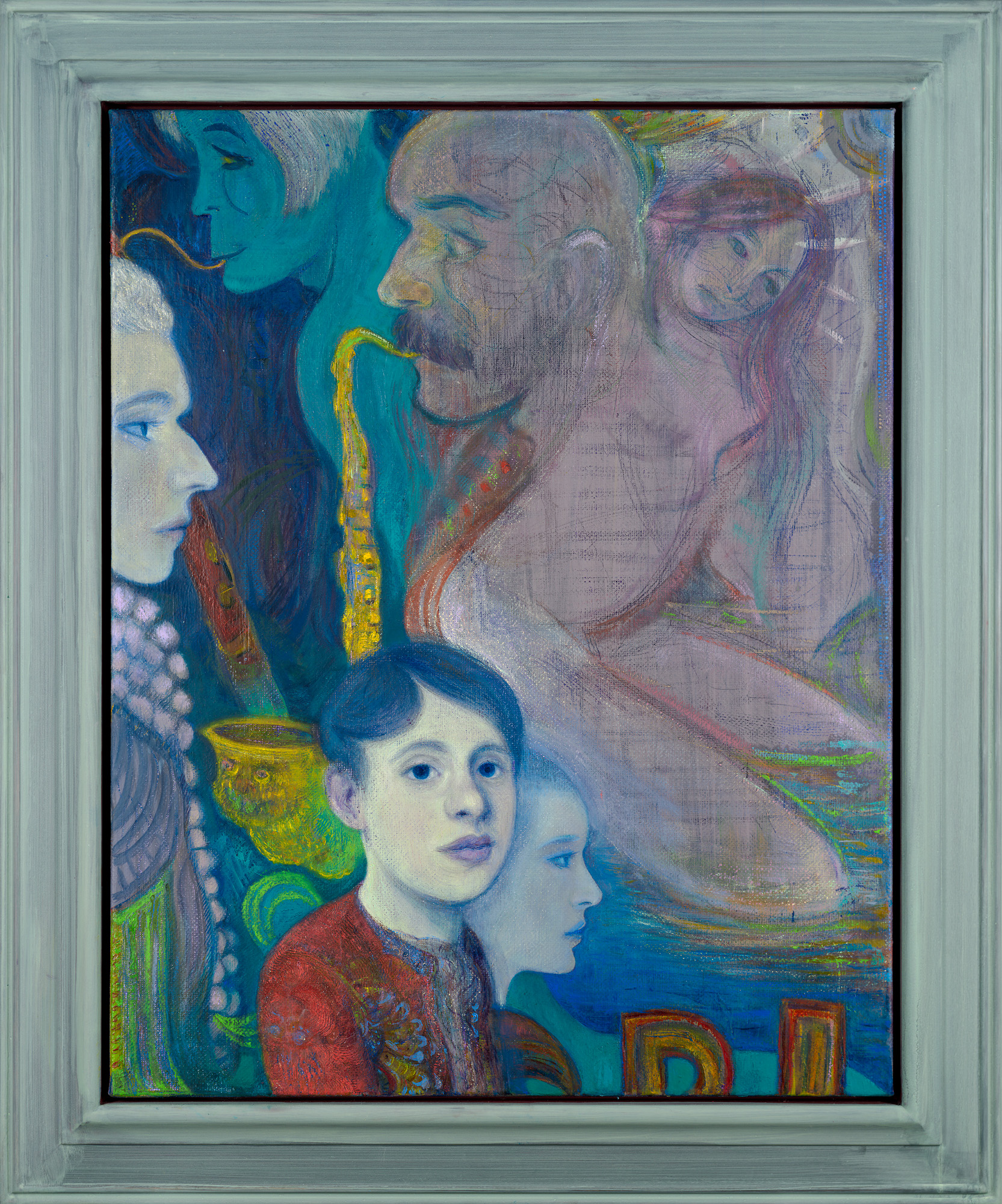

STEVEN SHEARER, Young Symbolist, 2013, acrylic and oil on canvas in artist’s frame, 94.5 × 80 cm. Collection of Allan and Sandy Switzer, Vancouver.

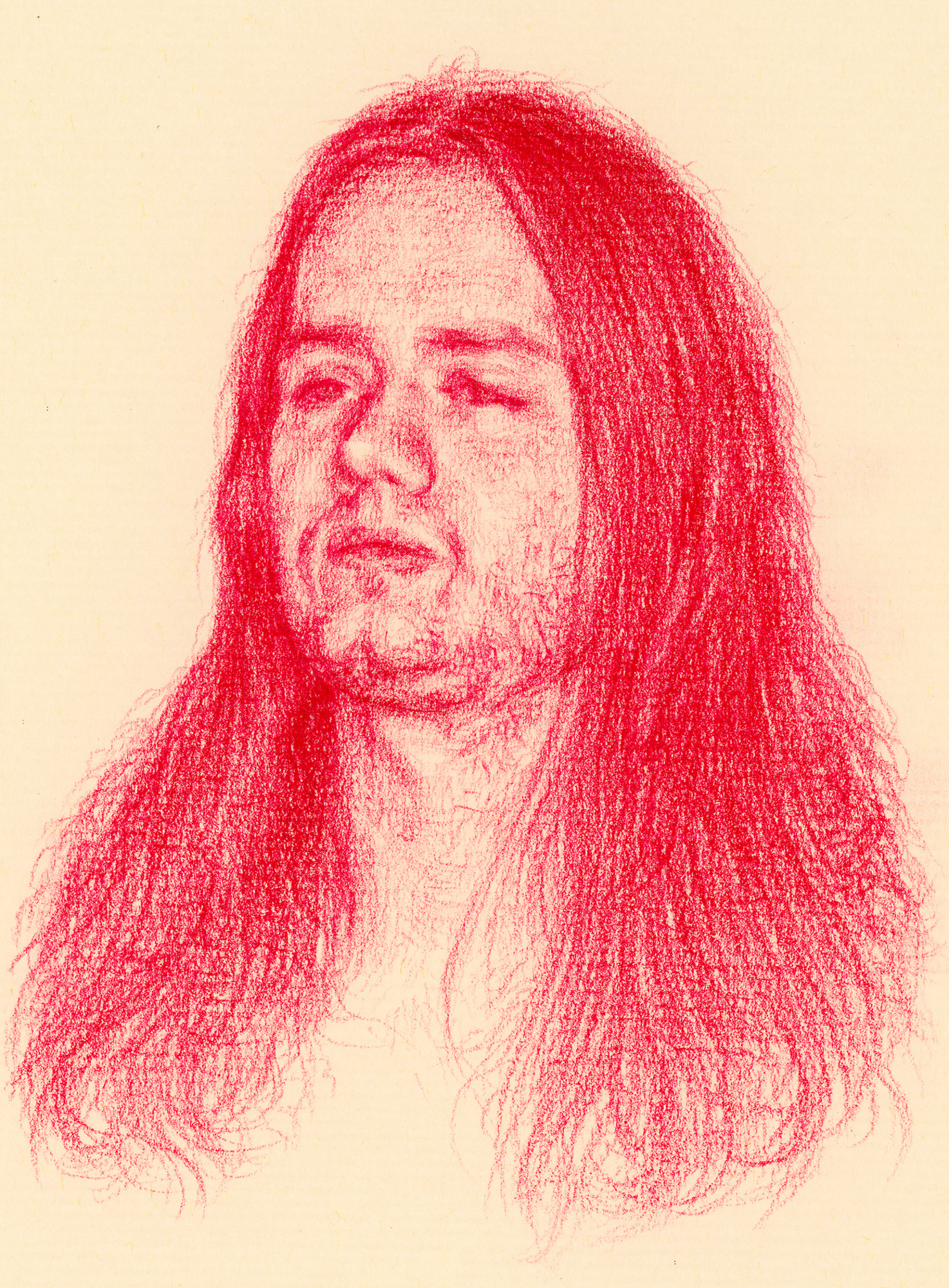

Through Shearer’s sympathetic eyes, the ecology of 1980s and ’90s metal culture unwittingly turns into a test site for the exploration of a “masculinity at the margins,” or a masculinity that, paradoxically and therefore all the more spectacularly, falls “outside the phallic pale” (to paraphrase critical theorist Kaja Silverman’s felicitous characterization). To name but one example, let us consider the case of Euronymous, the infamous front man of Norwegian Black Metal pioneers Mayhem, best remembered today for his extremist convictions, ghoulish passions, and violent death at the hands of a bandmate—the hallmarks of a hyperbolic punk machismo. Euronymous’s likeness features in Shearer’s suite of red crayon drawings, Longhairs (2004), in which a group of metalheads are rendered in such a way as to more closely resemble a cast of characters from a Bruegel painting. The cache of historical photographs that Shearer has used as the basis for his portraits of Euronymous, however, show the self-proclaimed leader of Norway’s Black Metal vanguard, which would later gain worldwide notoriety for a string of church burnings and actual homicides, adopting a stance of almost camp-like, self-consciously transgressive effeminacy. Euronymous’s curious image of libidinal defiance could be said to presage much of the complexities that attend the current high-octane debates swirling around the pluralized question of masculinities. It is this tangle of paradoxes, and the disarming of binary thinking, that make Shearer’s work from the mid-2000s so oddly prescient and his current work more topical still.

STEVEN SHEARER, Stairs, 2016, ink, oil, and oil pastel on canvas in artist’s frame, 226.5 × 94.5 × 5 cm. Collection of the Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut.

In the fall of 2018, I had the good fortune of seeing an exhibition of Shearer’s more recent work at his New York gallery Eva Presenhuber. The show, titled “The Late Follower,” allowed me to reconnect with the oeuvre of an artist I had lost sight of in the previous five years. It marked a considerable formal departure as well as a deepening of his recurring conceptual concerns, among which the aforementioned question of manhood, now cowering in the harsh light of the #MeToo movement and the Trump presidency, once again claimed center stage. For an artist who had chosen to retreat from art-world attention for the better part of the 2010s, presumably to better focus on his craft, it is fitting that this show should revolve so emphatically around the image of art-making, of artists at work in their studios, sculpting, painting, and “chiseling.” In Working from Life (2018), a bleary- eyed artist confronts us head-on, paintbrush in hand, his face partly obscured by the canvas he appears to be working on, in a manner reminiscent of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meniñas (1656), the urtext of all meta-artistic musings. Uncle Hermann (2018) features an apron-clad sculptor with a sickly yellow complexion, recalling German expressionist Hermann Scherer’s self-portraits. He clutches a diminutive female statue, like a glue-sniffing or absinth-addled Pygmalion, and is posing in front of a crumpled red cloth, invoking memories of Rogier van der Weyden’s unsurpassed mastery of painting draperies and folds. A similar arrangement recurs in Sculptor and Satyr from 2016, though here a long-haired artist of more ambiguous gendering is shown holding the legs of a male figure. In both The Chiseller’s Cabinet (2014) and The Late Follower (2017), finally, the primary subjects are lifelike male figures, cut off just below and above the pelvic region respectively, resting atop a plinth or stool. The latter painting is particularly complex and engrossing, a psychedelic meshwork of art-historical references and meta-medium commentary. If the central figure in it looks vaguely familiar to long-term followers of Shearer’s work, it is partly because he bears a distinct resemblance to the artist himself (again, a recurring trope).

STEVEN SHEARER, Longhairs, 2004, one of five pencil-on-paper drawings, 36 × 28 × 2.5 cm. Collection of the Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut.

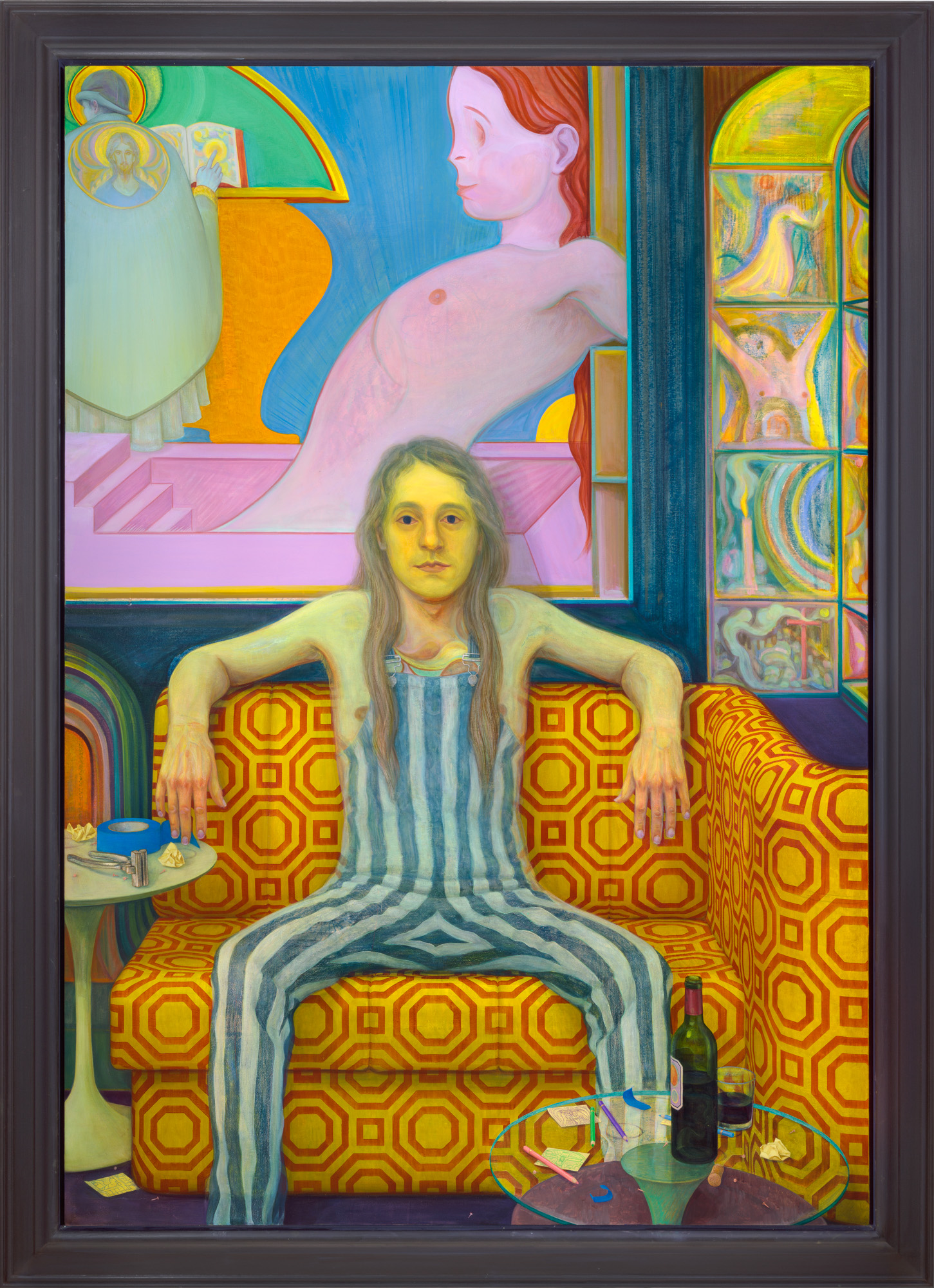

However, two of the exhibition’s most arresting works—the show’s true double-edged punctum, in my opinion—appeared to steer clear of these overarching self-reflexive concerns. In the first of this pair, Atheist’s Commission (2018), a young man in striped overalls looks directly at the viewer; he is seated in a geometrically patterned sofa and is surrounded by a puzzling array of objects (blue masking tape, crayons, crumpled yellow post-it notes, a half-empty bottle of red wine) rendered with almost photorealist precision—Shearer at his most technically proficient. In the background, a dense assortment of paintings- within-the-painting contain a string of religious motifs that help shed light on the artwork’s title. Yet the real subject of Atheist’s Commission is without a doubt the curious phenomenon known as “manspreading.” Although the sitter’s crudely striped pants lend the painting the lightly parodic charge of an Op Art exercise, there is no escaping the frontality of the man’s gaping crotch centered in the lower half of the composition—a curiously evasive assertion of “men’s rights.” (“Manspreading” was welcomed to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2015; although easily understood to be a “metaphor for men being given permission to take up more space in society,” the term has also been called a “gender-based slur” that is part of a male-directed shaming campaign.) A second painting, titled The Chiseller’s Figurines (2018), takes all of this up a notch. [1] In this work, a small sculpted figure depicting what we might think of as a “dirty old man” bears a passing resemblance to the bearded male in Shearer’s Fagan II from 2005. The figurine is shown mischievously flashing two children who amusedly stare at it from the painting’s bottom left corner. The little statue turns away from the viewer, toward the viewers in the painting, so this gaping crotch, too, is only hinted at: as elsewhere in much of Shearer’s art, the phallus casts the symbolic shadow of absence rather than presence. [2] The obscene delight of seeing Atheist’s Commission and The Chiseller’s Figurines paired in this way explicates the transgressive gambit of Shearer’s art. There is something deliciously joyful and liberating about the “wrongness” of the latter painting’s scene in particular—a joy that clearly resonates in the guileless smile of the onlooking child. A picture of a flashing perv rendered as exuberant high art—something about this painting of Shearer’s made me exhale with troubling relief when I first saw it in 2018, and this “something” surely relates, in one way or other, to the best definition I have ever heard anyone provide of art (its author was a Brazilian art critic called Mario Pedrosa): “the experimental exercise of freedom.”

STEVEN SHEARER, Sculptor and Satyr, 2016, oil on canvas in artist’s frame, 99.5 × 84.5 × 4 cm. Collection of the Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut.

The pictures of art-making assembled in “The Late Follower” intersect with the drawings and paintings referred to earlier, of young men in so-called corpse paint and tight leather trousers, via the notion, so central to Shearer’s work, of fashioning the self. One element of this self that we see being produced in his art, captured in the very process of production so to speak, is that of “being” male or masculine. The chiseller, the convalescent, Euronymous, the sculptor, the smoker, or Uncle Hermann—these are all figures in the midst of figuring it out, and pleasurably so. Shearer’s paintings have increasingly become pictures of this very pleasure. “Masculinity” is just another malleable material in the artist’s toolbox, much like it is in the hands of the men he enjoys painting.

STEVEN SHEARER, Atheist’s Commission, 2018, oil and ink on poly canvas, framed, 205.5 x 149.5 × 5 cm. The George Economou Collection.

STEVEN SHEARER, The Chiseller’s Figurines, 2018, oil and ink on poly canvas, in artist’s frame, 109 × 82.5 cm. Private collection.

[1] For some perspective, here are just four events that captured the public imagination during the first three weeks of the run of Shearer’s New York show: on September 16, 2018, Christine Blasey Ford came forward as the woman who accused Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault when they were in high school in Bethesda, Maryland; on September 25, Bill Cosby was sentenced to three years in prison for sexual assault; on September 27, more than 20 million people tuned in to witness Ford and Kavanaugh testify before the Senate on national television; and on October 5, one year after his outing in the New York Times, Harvey Weinstein’s house arrest began.

[2] In Newborn from 2014, an androgynous nude figure, again alluding to the specter of auto-portraiture, is depicted without the identifying marker of male or female genitalia.

STEVEN SHEARER was born in New Westminster, Canada, in 1968 and earned his BFA in 1992 from the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, where he continues to live and work. In 2011, Shearer represented Canada at the 54th Venice Biennale with the exhibition “Exhume to Consume.” The artist’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at prominent institutions worldwide.

DIETER ROELSTRAETE is the curator of the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago, where he currently teaches.

.jpg)