Elia Nurvista: Recipes for Reorientation

By Nicole M. Nepomuceno

Full text also available in Chinese.

Portrait of ELIA NURVISTA. Photo by Nonzuzo Gxekwa. All images courtesy the artist.

When we eat, we often ingest our conversations as our bodies do our meal, digesting simultaneously both flavors and ideas, aromas and speculations, textures and debates. Yogyakarta-born artist Elia Nurvista recognizes this. Her decade-long, community-based practice is lined with photographic documentation of people gathered around vibrant spreads of rice, curries, sautéed vegetables, grilled meats, and fresh fruits presented generously in bowls, on plates, or banana leaves. Other records show people cooking, with woks, teak leaves, and shallow bamboo baskets, in kitchens across Indonesia and elsewhere. In these gastronomic happenings, Nurvista fleshes out the question: what can the materials and processes we use to nourish ourselves say about our histories, our politics, and our societies?

ELIA NURVISTA, Tasting Memory, 2012, documentation of a workshop at Koganecho, Yokohama, 2012. Courtesy the Koganecho Area Management Centre.

The artist’s exploration in food began unassumingly: she moved into an apartment equipped with a large kitchen and was encouraged to try new recipes she found online. Working as a drafter for a design firm, she would browse recipes on the web during work, eager to pursue them after hours. Her search led her to internet forums where Southeast Asians who had migrated outside of their home countries would share possible recipe substitutes for native ingredients that are difficult to find in their new locale. Piqued by the mutability of enduring recipes and by food’s role in the migrant experience, Nurvista launched Tasting Memory in 2012 as part of her residency in Koganecho, a former red-light district in Yokohama. She asked migrants in the area: “What food reminds you of home?” and organized a series of lunches where they would share memories of their birth countries over Indonesian dishes. Recipes from across the globe embroidered with red thread onto furoshiki wrapping cloths, which are used frequently in Japan to wrap lunch boxes, were also shown in an installation as part of the work, recalling the capacity of food to trigger nostalgia and simulate, or even create, safe spaces.

From there, Nurvista’s practice came to mirror what art historian Claire Bishop writes of as participatory art, where “the artist is conceived less as an individual producer of discrete objects than as a collaborator and producer of situations; the work . . . as an ongoing or long-term project with an unclear beginning and end; while the audience, previously conceived as a ‘viewer’ or ‘beholder,’ is now repositioned as a co-producer or participant.” For instance, 3 Recipes 3 Generations (2014), created in collaboration with creative producer Alia Gabres in Yogyakarta and Melbourne, is an oral history project that uses recipes to explore cultural evolution across generations. For its Indonesian iteration, participants from three different generations shared their nasi goreng recipes, which they then cooked in isolation before serving them at a dinner party at the Kunci Cultural Studies Center. During dinner, Nurvista led the conversation, underlining how even with inhabitants of the same country, established recipes shift and change across time and space.

ELIA NURVISTA, Possibility of Inauthentic Recipes, 2018, documentation of workshop at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul, 2018. Courtesy MMCA.

The question of authenticity and cultural ownership comes in the two-part project Possibility of Inauthentic Recipes (2016 and 2018), executed first in Yogyakarta’s Studio Kalahan then at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul. “Do authentic dishes and recipes really exist, or are they a far-fetched idea that hints at our obsession towards ownership?” Materialized as a cooking class, the earlier edition of the work saw Nurvista cook Vietnamese banh flan and Rohingya fish curry at a downtown coffee shop. Banh flan is a caramel custard dessert that evolved from the French flan; its origins tell the story of France’s conquest over Indochina and how colonized societies have adapted the cultures of their colonizers through hybrid customs that continue to exist in postcolonial nation-states. In juxtaposition, the Rohingya people are a stateless Indo-Aryan ethnic group indigenous to Myanmar but who have been violently driven out of the country towards Bangladesh. When culture is conflated with national identity, and shared practices are forced to be understood only within arbitrary borders, what value does the claim of authenticity over cuisines have, and is anything ever truly authentic?

Beyond recipes, Nurvista has archived premechanized ways of cooking root vegetables in Dlingo, promulgated the scarcity-induced consumption of oil-production residue in Wonoasri, and critiqued the protracted history of the colonial sugar trade. Yet, the raw ingredient that occupies the most sizable share of her oeuvre is rice. “I’ve seen a lot of problems with rice,” Nurvista begins, before outlining the history of Indonesia’s Green Revolution, which was initiated in 1969 to increase rice production to levels that would make the country self-sufficient. The revolution introduced new technologies, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and high-yielding seed varieties but also crop diseases and a lower rice quality. A Free Trade Area launched by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 1992 ironically led to Indonesia importing better quality rice from Vietnam and Thailand, to the loss of its farmers.

Nurvista joined a meeting held by Javanese farmer groups with the Indian environmental activist and food sovereignty advocate Vandana Shiva in the summer of 2014. In an empty school classroom, they discussed the unjust prosecution of farmers who have been experimenting with patented seeds to cultivate new seed varieties. The state and corporations’ increased control of farmers’ land and production is another fault of the revolution as it has led to infringing farmers’ ability to operate. One hundred sacks of rice embroidered with phrases such as “The Last Rice from Java: Limited Stock,” “Rice of Hypocrisy: Unknown Quality Golden Rice,” and “Rice: From Seed to Suicide” occupied Fukutake House, at Japan’s Shodoshima Island, a year later in Nurvista’s As Long As We Can Import It, Why Bother Planting? (2015), an unmistakable critique of the Green Revolution’s shortcomings.

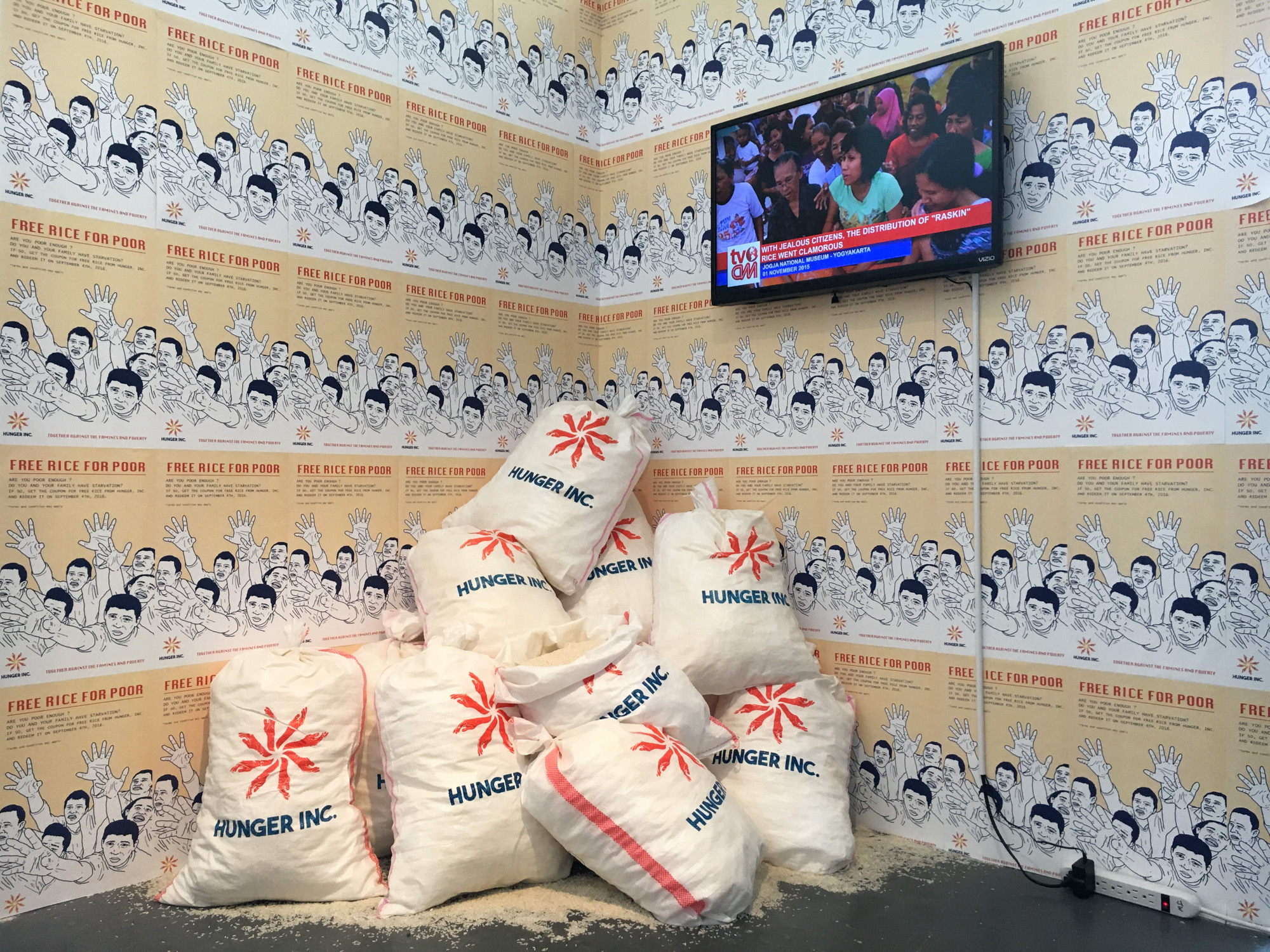

Installation view of ELIA NURVISTA’s Hunger, Inc., 2015- , mixed media installation, dimensions variable, at Kunstraum LLC, New York, 2016.

In Hunger, Inc. (2015– ), Nurvista further highlights the poor quality of rice distributed in the government-subsidized Raskin program for communities in poverty. An “aesthetic intervention” first presented at the 2015 Jogja Biennale, the multilayered project includes a fine-dining experience concocted using Raskin rice by a professional chef dubbed “Raskin Gourmet.” Presented in tandem are films about food made of out trash—parodies of the marketing campaigns by non-governmental organizations that sell poverty to obtain funds—and a video reenacting news footage of people fighting for rice. For the video, Nurvista asked Raskin beneficiaries themselves to recreate the scene of a hostile crowd struggling for rice as a form of catharsis. Hunger, Inc., in its many forms, shows how agricultural reforms and the ways in which our food is processed infiltrate tiers of society and politics, from the commodification of charity to the fetishization of human struggle.

Under Dutch colonial rule in Indonesia, rice was employed as a marker of extravagance and excess. Rijsttafel, which translates to “rice table,” is an elaborate form of dining that the Dutch adapted from the Indonesian nasi padang, where rice is served with multiple side dishes. Following its declaration of independence in 1945, Indonesia rejected rijsttafel among other colonial customs but the practice lives on in the Netherlands and Indonesian restaurants outside of the country. During a visit to London, Nurvista was surprised to learn that the Indonesian embassy still practiced rijsttafel and began researching the gap between its connotations in Europe and in Indonesia. Rijsttafel: The Flamboyant Table (2014) was a performative dinner held at the Delfina Foundation that outlines Nurvista’s findings. As they shared the rijsttafel, the participants ruminated on how the grand gesture was exercised to assert colonial power, and how it reflects the systems of abundance and greed that fuel colonialism.

Invitation to ELIA NURVIST’s Rijstaffel Revisited, 2014, a meal hosted at Delfina Foundation, London, 2014.

“The act of feasting with strangers became a power site of exchange,” Nurvista said. When we eat together, we share, we learn, and we organize. Strangers become acquaintances, and eventually, friends. Inflected into our meals are stories that span generations but equally reflect the realities of our current time and place. When we spoke, Nurvista was at an ongoing residency at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, working on her upcoming project on palm oil. For her, the work she does is not unlike that of object-based artists, for, despite their varied methods, their medium is “a platform, a room, a space for ideas to move and be contested.” In her lunches, dinners, and cooking workshops, Nurvista simultaneously carves out a forum open to mobilizing critiques and a sanctuary for nostalgic remembering. After eating, when the event is finished, the work lives on through the meaning it has imbued in its participants, the discussions that took place, and the relationships that were formed. Such work is dependent on what we take away as much as what has been put on the table.

.jpg)