Book Review: Expanded Vocabularies

By Chloe Chu, Peter Chung, HG Masters

Geofictions: Work in Progress

By Zara Arshad and Yaloo

Published independently, 2021

Instead of presenting research outcomes, design historian Zara Arshad and artist Yaloo’s Geofictions: Work in Progress reflects on the methods available for accruing knowledge, and highlights the crucial roles of serendipity, lived experience, and indeterminacy in information-gathering processes. The 191-page book was itself shaped by these factors: at the end of 2019, Arshad and Yaloo embarked on an investigation into human alterations of coastal ecosystems, guided by the questions, “How can we repair our relationship(s) with our natural environments? How do we build more- than-human empathy?” However, when Covid-19 scuppered their original plan for a three-month residency at Kaohsiung’s Pier-2 Art Center in 2020, the publication became a way for the two to press on with their inquiry and prospect different directions for the project.

To this end, Arshad and Yaloo pick the brains of researchers working in related fields, whose approaches and experiences are detailed in the fascinating interview section. Environmental historian David Fedman describes his examination of Imperial Japan’s interventions in Korea’s forestry in the 19th–20th centuries, and explained that his process took a decade due to the lacunae in the colonial archive, which he redressed with scientific studies and other visual and oral sources. Hong Kong-based architect Merve Bedir, who is tracking the effect of human activity on the ecosystems of Deep Bay, admitted that “there’s a lot of trying and experimentation, but ultimately ... while you can try to know everything as a researcher, there’s also so much you still don’t know, and will likely never know.” Juliana Kei shares the same sentiments in a conversation with fellow design historian Vivien Chan and curators Junyuan Feng and Alvin Li, who discuss their traveling exhibition “Liquid Ground”—presented at Hong Kong’s Para Site in 2021, and slated for Beidaihe’s UCCA Dune in 2022—and how land redevelopment throws material history into precarity. Noting the intersections of artistic and academic pursuits of knowledge, and the lack of hard evidence supporting her research on Vietnamese boat people in Hong Kong, Kei says: “The absence is so profound that even as historians, we...have to write speculative history.”

Similarly venturing into the unknowable, the excerpted renderings from Yaloo’s Seaweed Journal (2019–20) picture a world wherein humans are fused with autotrophic, carbon-absorbing seaweed to remediate the climate crisis. Elsewhere, Arshad’s and Yaloo’s visual research essay traces the development of five Asian port cities—Kaohsiung, Busan, Incheon, Shanghai, Hong Kong—from the 19th century onward, through archival maps and photographs. This section’s narrative is “more implicit than intended,” the authors confess in the introduction, and, indeed, the sparse captions ask that readers generate their own connective threads. Nevertheless, the essay contains the essence of the book, which underscores the limits and contingent nature of human knowledge, while reckoning with how one can hold onto one’s curiosity and attempt to understand the world we inhabit.

CHLOE CHU

The Extreme Self

By Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland, and Hans Ulrich Obrist

Published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, Cologne, 2021

We are living through a collapse of grand narratives. The accelerating failures of politics, global unrest, and an endless plague are unsettling our interior worlds. As our shell-shocked selves transmogrify, we are digitized into event logs in real time, wired with other data streams, and agglomerated into a resource to be extracted. Initiated by Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland, and Hans Ulrich Obrist to accompany their curatorial collaboration, “Age of You” (2021), The Extreme Self traces the morphosis of individuality with neologisms, Instagram comments, and epigrams overlaid on memetic images by more than 70 multidisciplinary creatives.

A mirror selfie of Jarvis Cocker differentiates corporal individuality from the virtual self that exists partly as simulacra and algorithms. The funhouse mirrors of social media distort us and our social distances, inducing what one page terms a “dysmorphia of the soul.” In the chapter titled “Post-Work,” a still from Cao Fei’s film Asia One (2018) is paired with job interview questions of tomorrow to probe the automation revolution and its consequences: we make up “personal story boards” to justify our labor, while Chinese men find companionship in chatbots. What has become of the human race in the age of silicon supremacy?

Elsewhere, blank instant-messaging bubbles signify how comment sections have become our real world, a public space too raucous to think in and full of irreconcilable differences. While pointing out our radicalization as online anons detached from consensus reality, the authors hastily reduce this to the horseshoe theory, asserting that both the political left and right trigger outrage and “microfascism.” Further highlighting social division, the words "Me,” “You,” “Us,” and “Them” are plotted on separate quadrants on a double- axis chart. Such simplifications are missed opportunities to explore the nuance of our atomized political present. A subsequent section, “Virtue Power,” surveys the extreme shifts of influence—in a world of influencers and populist despots, our everyday identity signalling and PSYOP take hold of our lives. Beyond these performances, who possesses power?

The book closes by revealing our quasi-religious impulse as we edge ever closer to the end times. Whether it is toward primitivism or an immaterial metaverse, the desire to exit is timeless. However, our rituals have been updated: “Technologians are now our magic individuals.” A civilization guided by Silicon Valley solutionism traps us in samsara, eternally chasing the next big thing while cult leaders ascend to space. Though The Extreme Self is an effective aggregation of the new languages describing our new selves, the musings are at times sensationalized. Replicating theorygram (the community of critical philosophy meme pages) by curating a group of established artists has its limitations—the absence of memers, conspiracists, and ordinary Gen Zs results in a lack of the most impactful images at present. The last page places the sentence “restore me to factory settings” on top of a latex-cast head of David Bowie (the prodigy of the extreme self), promising only mystery for our cosmic chaos.

PETER CHUNG

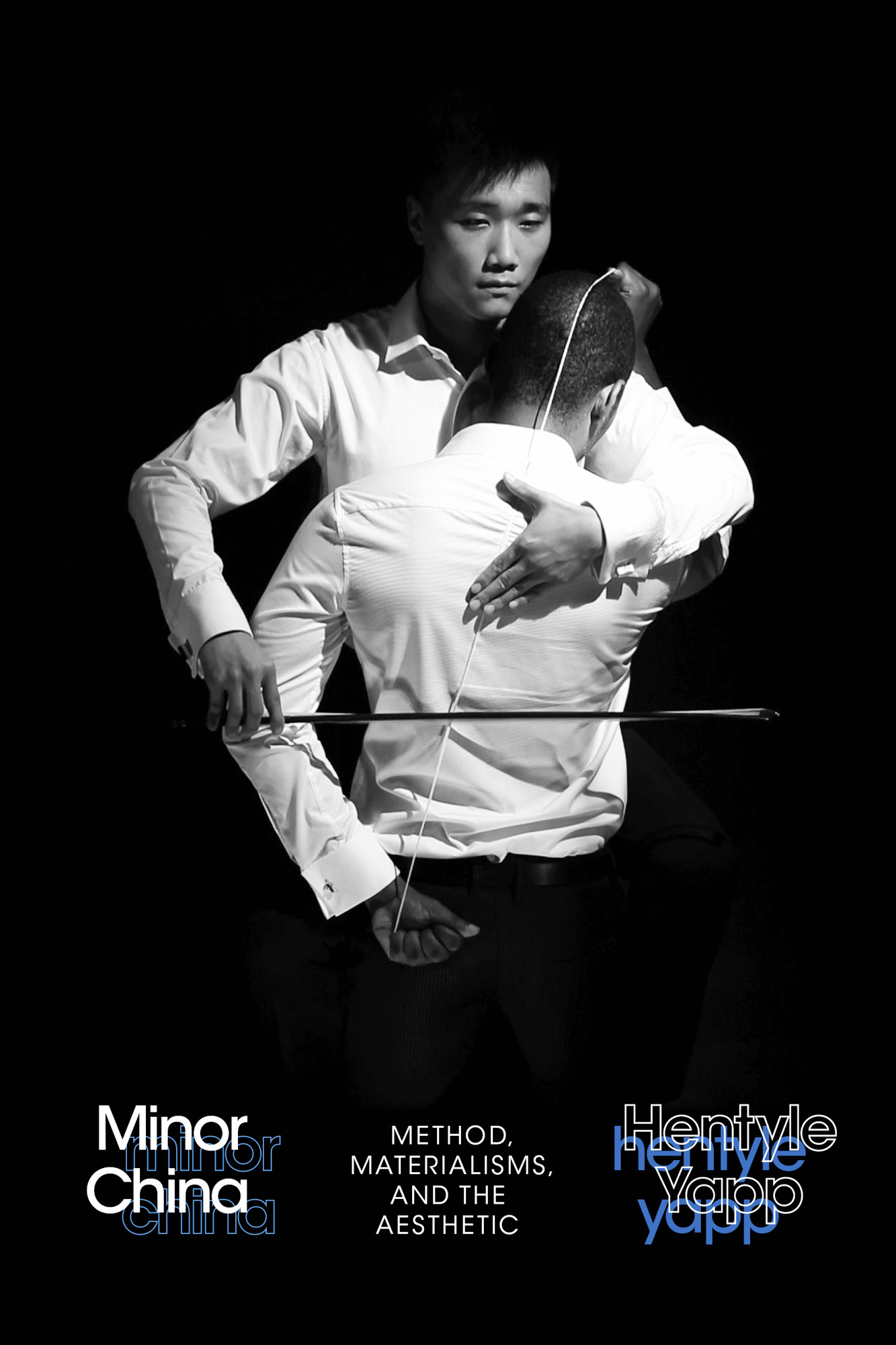

Minor China: Method, Materialisms, and the Aesthetic

By Hentyle Yapp

Published by Duke University Press, Durham, 2021

State censorship has been both the bane of Chinese art at home and its enabler abroad, allowing a narrative of alterity to propel artists onto the world stage since the 1990s. In Minor China: Method, Materialisms, and the Aesthetic, scholar Hentyle Yapp pushes back against this liberal political paradigm of the avant-garde artist rebelling against the repressive state by reading the aesthetic nuances—the “minor”—in the practices of artists who are in reality reluctant to join the “logic of the major” that demands Western- legible discourse about the cultures of the non-West. One only needs to look at the sensationalism around Ai Weiwei, Yapp proposes, to understand what happens when an artist becomes “tethered to expected, major narratives circumscribed by a set of key terms: history, the state, subject, and agency.”

What Yapp means by the “minor” is crucial to appreciating the scholar’s larger ambitions to counter “normative Marxist or liberal frameworks,” and requires an appreciation for the affective turn, as well as the decentering of human narratives and rise of speculative realism in critical theory of the last decade. The minor, as Yapp glosses it, is what rejects the dominant modes of engaging with art on the levels that privilege explicit meaning over emotion (affect), visuality over other sensations (sound, touch, smell, etc), humans over other living creatures, and concrete solutions over imagination. This allows the scholar to re-read even the most iconic, and iconoclastic, works of Chinese contemporary art—like Zhang Huan covering himself in honey and fish sauce and sitting on a public toilet until he’s covered in flies in 12 Square Meters (1994)—as not rooted in a “masculinist notion of challenge” but as a way of contending with “less determined modes of consciousness,” and not as a model of political agency or endurance but a “lingering in power, pain, and time.”

While critical readings rooted in affect theory often conclude with these kinds of low-impact descriptions, that is precisely the point. In reading Minor China, one does feel intensely the super-heated political pressure placed on Chinese culture by the world—and particularly in the United States, where a monolithically conceived China plays a threatening Other to the waning American global imperial project. When Yapp finally escapes this dialectic cacophony of a “major” civilizational clash, particularly by looking at the musically rooted work of Hong Kong artist Samson Young, the concept of the “minor” comes into its own. Young’s “sense of sincerity,” Yapp rightly finds, allows the artist’s exploration of the roles of music, sound, and speech in the greater culture and history of China to swerve away from “prescribing a solution or explicitly critiquing this condition” and instead reveals Young’s efforts to depict “the structural and atmospheric [conditions] that dictate how to render legible his own life.” In Young’s works, Yapp can finally attune readers to what every artist ultimately wants for themselves: to be listened to carefully in their own key.

HG MASTERS

.jpg)