The Museum of Without

By Dane Mitchell

A robot designed by the Institute of Digital Archaeology carving a 3D replica of the Parthenon Marbles. All images courtesy the Institute of Digital Archaeology and Robotor, Italy.

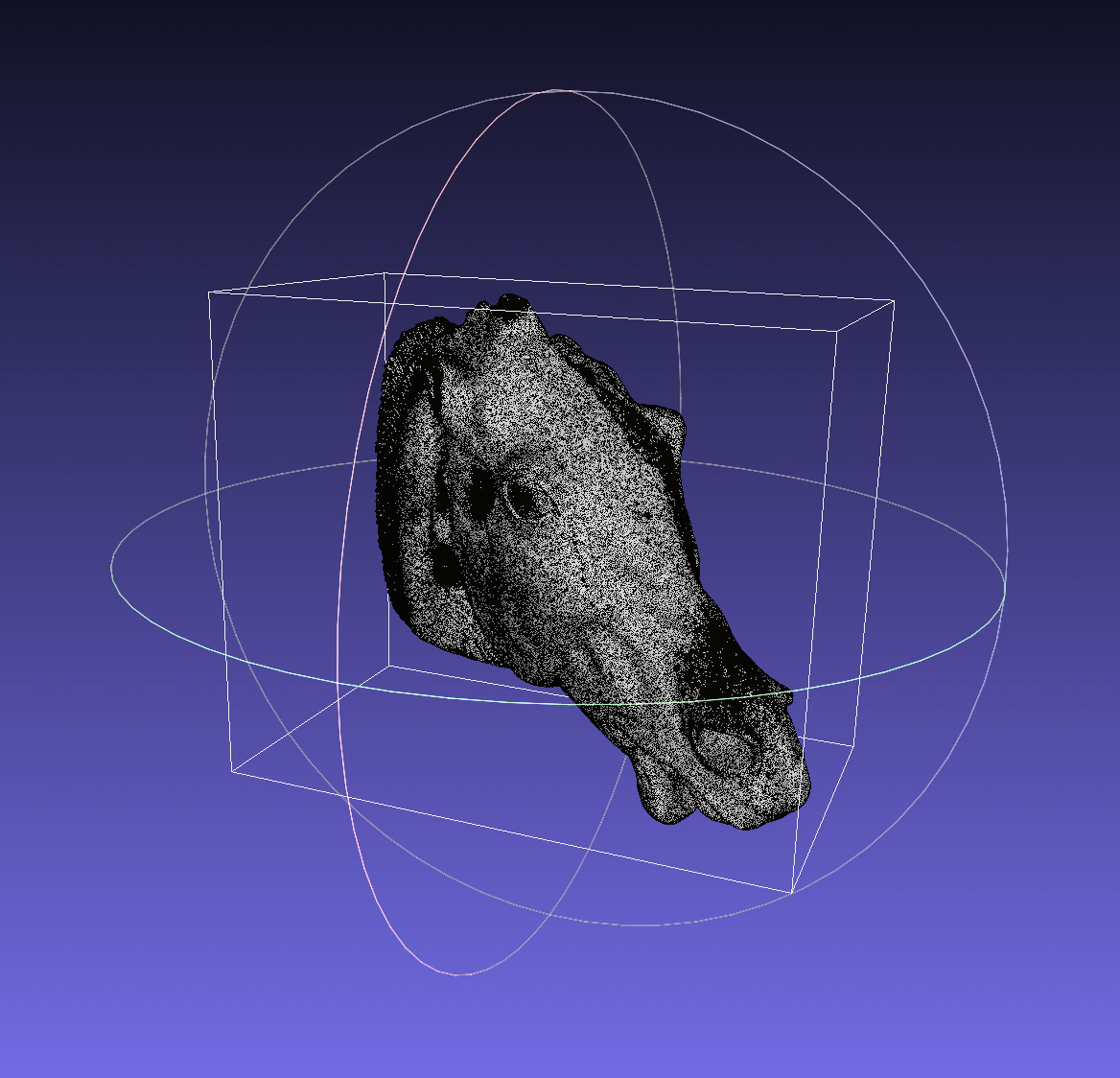

In July, an article was published in The New York Times titled The Robot Guerrilla Campaign to Recreate the Elgin Marbles. The text outlines a project of the Institute of Digital Archaeology, a University of Oxford-based research group. Using photogrammetry software on multiple iPhones and iPads, the researchers have clandestinely scanned some of the Elgin Marbles (from here on I’ll call these the Parthenon Marbles) at the British Museum. Their sole motivation is to replicate these classical Greek sculptures so that the originals may be returned to Greece, leaving the British Museum with life-size facsimiles to be consumed by its audience. Drawing on the group’s data, replica Parthenon Marbles are being carved by a technological hand.

The article was illustrated with photos by Francesca Jones, showing the process behind the creation of these replicas. Seeing these images opened for me the revolving doors to an alter-museum. Not only do these replicas prehensively in-fill the space left by the originals’ potential return to Greece (don’t hold your breath), they suggested to me the possibility of imagining The Museum of Without.

The Museum of Without is one without objects, artifacts, and artworks; it is a museum of proxies and gaps—an unhinged museum that presents itself to us in a full state of absent-hood, held together by its hermeneutical framing practices alone, which display the techniques of enclosure. It actively asks: what might a museum without artifacts be? What might a collection of losses hold and what might hold it?

A screenshot of the 3D model of the Parthenon Marbles replica.

Back in October 2019, The New York Times gave a behind-the-scenes peek into the Museum of Modern Art’s curatorial machinations as it prepared a full rehang of its collection in its new galleries following a USD 450 million expansion. The article is scattered with around 20 images by photographer Jeenah Moon of the progress of this rehang. Two of Moon’s images were taken in a gallery in which the work of Constantin Brancusi was to be installed. One image features two installers, nitrile gloves on, steadying the sculpture Endless Column (1918) to confirm final placement—except they weren’t. The other, a wide-shot of the full gallery, pictured three low, square plinths with around a dozen works by Brancusi conventionally placed, MoMA style—except they weren’t. Both images in fact show full-scale cardboard dummies of these works. These thoughtfully made surrogates, beside serving a practical purpose for testing work placement, drew attention to how adaptable we might be to new notions of authenticity and the potential for a museum to be full of things at the same time as it is emptied of them.

These Parthenon Marbles replicas and Brancusi dummies remind us that objects, including those unrepatriated spoils stored in the vaults of museums, are in constant movement—that all things are migratory and transitory—be that ideologically, through the re-appraisal of contested histories, or materially, through the initial movement of objects away from and, perhaps now more than ever, back to their points of origin.

Dane Mitchell is an artist based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. His solo exhibition "Unknown Affinities" is on view at Two Rooms, Auckland, from August 12 to September 10.